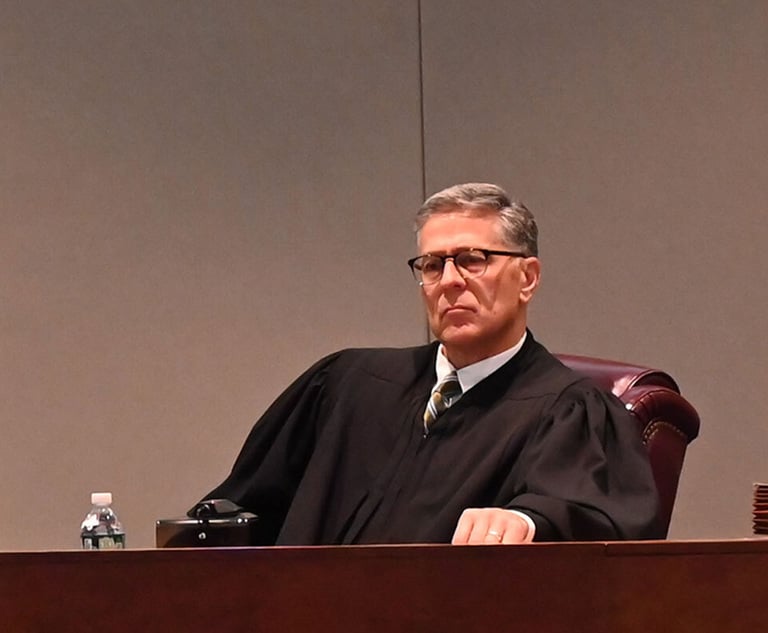

New Jersey Supreme Court Justice Associate Justice Douglas M. Fasciale. Credit: Screenshot from Twitter

New Jersey Supreme Court Justice Associate Justice Douglas M. Fasciale. Credit: Screenshot from Twitter'A More Nuanced Issue': NJ Supreme Court Considers Appellate Rules for Personal Injury Judgments

“Thus, even if we concluded that [plaintiff] met prong one, she is unable to show that prevailing on the trial court evidentiary ruling will not impact the final judgment and only potentially increase it,” Justice Douglas M. Fasciale said.

January 15, 2025 at 05:43 PM

5 minute read

The New Jersey Supreme Court held that litigants who accept a final judgment in a personal injury case may still appeal as long as they have made that intention clear, and that resolution of the appellate issue will not affect the judgment other than increasing the benefit, according to a decision filed Wednesday.

Associate Justice Douglas M. Fasciale penned the opinion for the court, affirming that the Appellate Division appropriately dismissed an appeal as moot in a case captioned Brehme v. Irwin. After a jury awarded the plaintiff, Linda B. Brehme, $275,000 for pain and suffering and past lost wages, the trial court entered a final judgment in July 2022. Brehme's counsel also signed a warrant to satisfy the judgment, but days later he attempted to file an appeal after she received nothing for future lost earnings, according to the state high court's opinion.

The judge said that under common law, the long-standing rule was that litigants cannot appeal a final judgment if they have accepted an award. However, Fasciale cited a 1958 state high court opinion in Adolph Gottscho v. American Marking, which clarified that the appealability of a final judgment is a more nuanced issue.

“In other words, the court clarified that a party is not estopped from appealing a separable issue, even when a party accepts the benefits of a final judgment, if the only issue raised on appeal would increase the benefit awarded to the party appealing, but not impact the accepted, underlying final judgment," Fasciale wrote.

Thomas Irwin rear-ended Brehme’s car in December 2016. After her carrier paid benefits, but not up to her policy limits, Brehme filed suit against Irwin in Bergen County Superior Court. The trial judge denied her motion to admit projected future medical expenses into evidence because she had not exhausted her policy limits. A jury ultimately awarded Brehme $225,000 for pain, suffering, disability, impairment, and loss of enjoyment of life, as well as $50,000 in lost wages but nothing for future lost earnings, according to the state high court's opinion.

A final judgment was entered and Brehme’s attorney deposited the funds into his trust account and signed a warrant satisfying judgment. However, when Brehme tried to appeal, the Appellate Division rejected her claim as moot because she received full payment and her attorney signed the warrant.

The New Jersey Supreme Court agreed.

Citing the Gottscho court, Fasciale said Brehme was required to satisfy two prongs to be able to appeal. First, she had to make her intention to appeal known before accepting payment of final judgment and before executing a warrant to satisfy that judgment. Additionally, if she were to prevail on appeal, that issue must not impact the final judgment other than potentially increasing it.

“A defendant may pay a final judgment for several reasons,” Fasciale said. “The most obvious reason is to end the litigation. Irwin did that here. Final payment and execution of a warrant to satisfy judgment without the other party’s knowledge that a plaintiff plans to appeal does not promote finality, efficiency, or fairness.”

In Brehme's case, the court determined she did not make it known that she intended to appeal before accepting final payment and executing the warrant. As for the second prong, the judge found that prevailing on her appellate issue would change the final judgment.

The justice explained that it is well-established that personal injury awards are generally not divisible. He added that is especially true where pain-and-suffering evidence is linked to future medical expenses.

“One jury cannot hear evidence relevant to pain and suffering and another jury hear evidence relevant to future medical expenses,” Fasciale said. “Assuming the admissibility of future medical expenses in this case, the two claims—pain and suffering and future medical expenses—would have to be considered simultaneously. Those claims cannot be fairly adjudicated separately.”

In part, Brehme also argued that the appellate court erred in rejecting her claim because she complied with court rules 2:4-1 and 4:48-1. Under R. 2:4-1, appeals of final judgments must be filed within 45 days of their entry. Under R. 4:48-1, when a party satisfies a final judgment, a warrant must be executed. Brehme alleged that R. 4:48-1 does not alter the 45-day period prescribed in R. 2:4-1. Fasciale disagreed, stating that neither rule barred her appeal but that neither supported it either.

Brehme argued that she satisfied the notice prong since Irwin filed the warrant on the same day she filed her appeal. Fasciale disagreed and said that what matters is the day the warrant is signed, not the day it is filed.

”But Rule 4:48-1 also does not explicitly address the legal effect of accepting a judgment and executing a warrant to satisfy the judgment before filing a notice of appeal,” Fasciale said, asking the Civil Practice Committee to clarify R. 4:48-1 in light of this case.

Fasciale was joined in his opinion by Chief Justice Stuart Rabner and Associate Justices Anne M. Patterson, Fabiana Pierre-Louis, Rachel Wainer Apter, Michael Noriega and John Hoffman.

Counsel for Brehme, Gerald H. Clark of the Clark Law Firm in Belmar, and counsel for Irwin, Carl Mazzie of Foster & Mazzie in Totowa, did not immediately return requests for comment.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Seton Hall Escapes COVID-19 Wrongful Death Suit After Student Found Dead in Dorm

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1‘Facebook’s Descent Into Toxic Masculinity’ Prompts Stanford Professor to Drop Meta as Client

- 2Pa. Superior Court: Sorority's Interview Notes Not Shielded From Discovery in Lawsuit Over Student's Death

- 3Kraken’s Chief Legal Officer Exits, Eyes Role in Trump Administration

- 4DOT Nominee Duffy Pledges Safety, Faster Infrastructure Spending in Confirmation Hearing

- 5'Younger and Invigorated Bench': Biden's Legacy in New Jersey Federal Court

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250