The Law Firm Disrupted: A Hitch in a 'New Law' Business Model

Virtual law firms are increasingly popular, but they may also be vulnerable to group departures or spin-offs.

December 14, 2017 at 09:00 PM

7 minute read

Hello, and welcome to another edition of The Law Firm Disrupted. I'm Law.com reporter Roy Strom, and this weekly email briefing attempts to make sense of the biggest challenges and opportunities facing law firms today. Let me know what you think at [email protected].

➤➤ Sign up here to receive next week's The Law Firm Disrupted straight to your in-box.

A Hitch in a 'New Law' Business Model

One of the most widely-read stories I wrote for The American Lawyer this year had a catchy headline: “Stay-at-Home Rainmakers: A Growing Threat to Big Law.”

One reader commented that “stay-at-home” has a connotation different from “work-from-home.”

May be true. But the headline worked!

Either way, I was talking about the growing trend toward “virtual” or “cloud-based” law firms.

For the uninitiated, such firms typically work like this: Lawyers keep up to 80 percent of the revenue they generate. They give the other 20 percent to the owners of the firm. And they typically work from home, providing their own technology and, in some cases, paying for their own marketing materials.

While it is true that these firms are increasingly popular, they may also be dealing with a structural flaw that exacerbates the risk of silos within their ranks.

The symptom of that flaw is group departures or spin-offs.

The most recent of which came this week, when a group of five partners split from Culhane Meadows to form Edwards Maxson Mago & Macaulay, or “EM3 Law.” Culhane Meadows is itself a spin-off from another virtual firm, FisherBroyles. Culhane Meadows launched in 2013 with four founding partners from FisherBroyles and within a month had 16 former lawyers from that firm working in the new “cloud-based” shop.

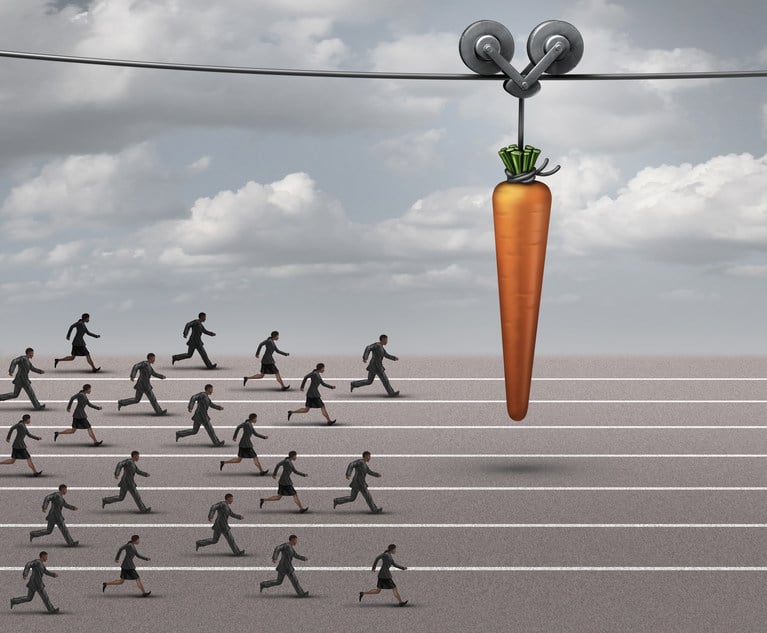

Many ex-Big Law partners have been drawn to virtual firms for the freedom from traditional firm bureaucracy and the chance to keep a larger share of their fees. But what happens when a group of, say, five partners find themselves working together almost exclusively within that model? Why kick 20 percent back to the firm? After all, you own the ink in the printer. And you pay the mortgage.

“I've heard other partners at so-called virtual firms express those sentiments,” said Jamal Edwards, who launched EM3 this week, less than a year after joining Culhane Meadows. “I've felt them myself in the past.”

To be sure, Edwards said those aren't the reasons he left Culhane Meadows. He and his partners wanted to tweak the virtual model (a word he said does not describe his new firm). While EM3 Law's compensation system will include a kickback to the firm, Edwards said that will be capped at some level, with the excess being returned to individual partners.

“Our goal is to take the amount that's necessary to support the firm, and make sure the firm is financially solvent and has a cushion,” Edwards said. “But once we hit that amount, [we will] allow that to go back to the partners as opposed to taking a significant amount of that to enrich the owners of the firm.”

In other words, it's a question of the value the firm itself provides for the cost of membership.

While traditional firms are not immune to spinoffs, the calculus of the value they offer partners is not (usually) as dollars-and-cents focused. Partners in Big Law value the Class A office space, the firm's brand, their colleagues (and their institutional clients) and the prestige that comes with it all. And, of course, Big Law provides a level of financial security that virtual firms make no pretense to match.

I put all this to Frederick Shelton, CEO of legal search firm Shelton & Steele, where he specializes in partner recruiting and business consulting specifically for virtual and small- to medium-size firms.

Shelton disagreed that virtual firms were more prone to spin-offs or to silos forming within their partnership. He said most of the handful of virtual firms he works with make about 30 percent of their revenue from cross-selling between practice groups or geographies.

But one reason Shelton said partners may be willing to step out on their own from virtual firms is that they have already taken law firm entrepreneurship out for a “test drive.”

“It's not this huge step,” Shelton said.

Virtual firms should look for ways to provide value to partners outside of their compensation. If their value is simply taking less of a lawyer's fees than Big Law, there is little a firm can do to keep partners who still want more.

Looking for Your Help

This news out of Canada caught my eye, and I'm interested in hearing from similarly situated attorneys. Toronto-based Aird & Berlis announced it is working with automated contract review software company Diligen. But the part that tugged at me is this: An associate from Aird & Berlis, Aaron Baer, will be “seconded” to Diligen to help the company find other uses for its software and to train the system to identify other legal concepts.

Earlier this year I wrote a story about Bryan Cave's attempts to train lawyers to use technology to disrupt its business. I'd like to take that one step further and write about lawyers who are actually empowered to put new technology to work at their firms. I know of a couple young associates or junior partners who are using technology expertise (coding) to do things such as create automated document workflows or build expert systems. If you know of others (or if you are one yourself), please reach out to me at [email protected]

Roy's Reading Corner

On Data Analytics: The Financial Times reports on three law firms that are using data analytics in interesting ways. I've read about two of the initiatives: DLA Piper's tool that spots clients who may be about to leave the firm, and Littler Mendelson's data push driven by data analytics director Zev Eigen.

But I'd not heard about Kirkland & Ellis' database of information from the deals it advises on. From the FT: “Its CTRAN database, which all its lawyers can access, includes figures from deals where the firm represented a party in the transaction, including information on financing terms and ways that buyers allocate the risk of financing failure.” CTRAN apparently dates back to 2008, and data from the proprietary database is often used to generate graphics in the firm's newsletters. FT reports that Kirkland is currently developing CTRAN 3.0.

Automate This: A Swiss firm, Meyerlustenberger Lachenal (MLL), is selling its documents related to corporate mergers. The firm is doing that through a website called PartnerVine launched in October that currently sells legal documents from accounting giant PricewaterhouseCoopers. MLL said it will sell documents related to intra-group mergers—transactions involving one company—with the plan that in-house counsel will call them for support when needed.

“That is the best way to integrate the advantages of tech with our comprehensive legal expertise,” said Alexander Vogel, head of corporate finance at MLL in Zurich.

Hey, at least it isn't free.

Ready, Set, LPO: At The American Lawyer, Hugh Simons and Nicholas Bruch write about the coming competition among legal process outsourcers in the wake of news that DXC Technology Co. will outsource part of its in-house legal department to UnitedLex Corp. One interesting prediction is that a large company with a high-performing legal department might spin part of it off to offer its services to other companies. Perhaps clients really are the competition!

That's it for this week. Thanks for reading, and please send any feedback (including criticisms or rebuttals) to [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Dechert Sues Former Attorney for Not Returning Compensation

Law Firms Are 'Struggling' With Partner Pay Segmentation, as Top Rainmakers Bring In More Revenue

5 minute read

The Right Amount?: Federal Judge Weighs $1.8M Attorney Fee Request with Strip Club's $15K Award

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250