Judge Disqualifies Baker & Hostetler Partner From Defense of First Bellwether Opioid Trial

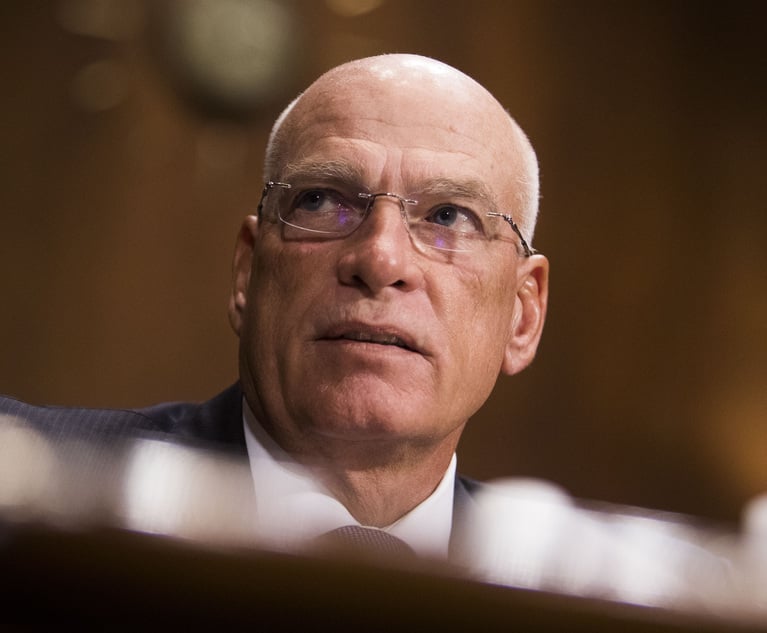

U.S. District Judge Dan Polster disqualified the firm and Cleveland partner Carole Rendon, who represents Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. but previously headed an opioid task force while serving as U.S. attorney of the Northern District of Ohio from 2016 to 2017.

March 25, 2019 at 05:34 PM

5 minute read

A federal judge has disqualified Baker & Hostetler and a key partner, Carole Rendon, from defending one of the opioid manufacturers in the first bellwether trial over the addiction epidemic.

Rendon, a partner in Cleveland, represents Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. but previously worked as a federal prosecutor in Ohio, including as U.S. attorney of the Northern District of Ohio from 2016 to 2017. During that time, Rendon was head of a heroin and opioid task force that included officials from Cleveland and Cuyahoga County. U.S. District Judge Dan Polster focused on that task force in his March 20 disqualification order.

“In community relations, just in personal relationships, years of trust can be undone in a very short period of time,” he wrote, noting that when he began his career as a federal prosecutor in 1976, there was mistrust among the various law enforcement agencies that such task forces later alleviated. He concluded “under the unique facts of this case, it is not appropriate for Ms. Rendon, or her firm, to represent Endo in a trial against the city of Cleveland or Cuyahoga County.”

The order follows a Feb. 6 hearing at which Polster heard testimony from three public officials and Rendon. At the end of the hearing, he said he would reach out to the U.S. Department of Justice to determine whether to disqualify Rendon and her firm. Attached to the order was a March 15 letter from the U.S. Department of Justice's civil division stating that Rendon had access to nonpublic information.

Polster's order is limited to the first trial in the multidistrict litigation, slated for Oct. 21, in which Cuyahoga and Summit counties, both in Ohio, have sued opioid manufacturers and distributors for causing the epidemic. The order also applies to a case brought by the city of Cleveland, planned for a later trial.

Hunter Shkolnik, a partner at Napoli Shkolnik, who represents Cuyahoga County, said in an emailed statement, “We appreciate the careful consideration Judge Polster has given to a very difficult issue and further appreciate the additional steps taken by referring the matter to the Department of Justice for guidance. A fair judicial process is critical. Today's decision is a step in that direction.”

Polster allowed Rendon and Baker & Hostetler to continue to represent Endo in the multidistrict litigation, which involves more than 1,600 lawsuits by other cities and counties across the country. Rendon also is co-liaison counsel for all the manufacturing defendants, many of which filed documents joining in Endo's opposition to the disqualification motion.

Matthew J. Maletta, executive vice president and chief legal officer for Endo, wrote in an emailed statement: “I agree with Judge Polster that Carole Rendon is an excellent attorney who served the Department of Justice with great distinction. I respectfully disagree, however, with both his analysis and his decision to disqualify Ms. Rendon and Baker [&] Hostetler from representing Endo in opioid cases involving Cuyahoga County and the City of Cleveland. Endo is currently evaluating its options with respect to Judge Polster's decision.”

Rendon and a Baker & Hostetler representative did not respond to a request for comment.

The order follows a motion by Cleveland, joined by Cuyahoga County, to disqualify Rendon and Baker & Hostetler from the opioid MDL, citing violations of the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct, specifically Rule 1.11, which bars former government attorneys from representing a client “in connection with a matter” in which they participated or when possessing confidential government information.

Rendon and Baker & Hostetler insisted there was no conflict.

Polster found that the opioid case wasn't a “matter” that Rendon worked on while serving as a federal prosecutor. But, he concluded, she had access to confidential information, citing the letter from Lisa Olson, senior trial counsel at the federal programs branch of the U.S. Department of Justice's civil division. That information, according to the letter, included “inadequate staffing levels, funding deficiencies, strategies, initiatives operations, and allocation of resources at the county and local levels for dealing with the opioid crisis.”

“The court concludes, based upon its understanding of this litigation, that this confidential non-public information may go to the heart of plaintiffs' damages claims, and this information, if used by Endo, could 'materially prejudice' Cleveland and Cuyahoga County,” Polster wrote.

He noted that he placed “considerable significance” on the testimony of one of the witnesses at last month's hearing: Gary Gingell, commander of Cleveland's Division of Police, who was on the task force with Rendon. When asked how he felt with Rendon at his deposition, Gingell had testified, “Personally, I was very uncomfortable, extremely uncomfortable.”

But Polster also acknowledged concerns raised in an amicus brief by 20 former U.S. attorneys, from states including Florida, Texas, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Georgia and California, that too many restrictions could make it harder for lawyers in government to change jobs.

“Ms. Rendon's work on behalf of the United States and specifically her work on the opioid task force should not, and indeed does not, disqualify her and her firm from serving in a leadership capacity in the opioid MDL or participating in any trial involving claims by other cities and counties,” he wrote. “It is only the confidential information she received specific to the city of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County that disqualify her and her firm from participating in those two cases.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Serious Disruptions'?: Federal Courts Brace for Government Shutdown Threat

3 minute read

'Unlawful Release'?: Judge Grants Preliminary Injunction in NASCAR Antitrust Lawsuit

3 minute read

'Almost Impossible'?: Squire Challenge to Sanctions Spotlights Difficulty of Getting Off Administration's List

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Customers: Developments on ‘Conquesting’ from the Ninth Circuit

- 2Biden commutes sentences for 37 of 40 federal death row inmates, including two convicted of California murders

- 3Avoiding Franchisor Failures: Be Cautious and Do Your Research

- 4De-Mystifying the Ethics of the Attorney Transition Process, Part 1

- 5Alex Spiro Accuses Prosecutors of 'Unethical' Comments in Adams' Bribery Case

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250