Will the Church Sex-Abuse Grand Jury Report Lead to New Civil Suits?

While some attorneys said the report could lead to a wave of new cases, other lawyers were skeptical and said there likely won't be much effect on sex abuse litigation in Pennsylvania without changes in the law.

August 14, 2018 at 05:03 PM

6 minute read

Credit: Thoom/Shutterstock.com

Credit: Thoom/Shutterstock.com

According to a high-profile grand jury report the state Supreme Court released Tuesday, thousands of children were sexually assaulted at Catholic dioceses across Pennsylvania. The report documented cover-up efforts by church officials, and said more than 300 predatory priests were able to abuse children for decades.

However, while some attorneys said the report could lead to a wave of new cases, other lawyers were skeptical and said there likely won't be much effect on sex abuse litigation in Pennsylvania without changes in the law.

The grand jury report, which is more than 880 pages and includes more than 450 pages of responses, outlined abuse that occurred in six dioceses in Pennsylvania spanning the past 70 years.

Although the report names many of the abusive priests, it was redacted to remove the names of some of the alleged abusers who claim that the grand jury proceedings violated their due process rights.

The state Supreme Court is set to examine those arguments next month and will ultimately decide whether the report is eventually released in a more transparent form. However, one attorney said that regardless of the version, the report could still serve as the basis for numerous new civil claims.

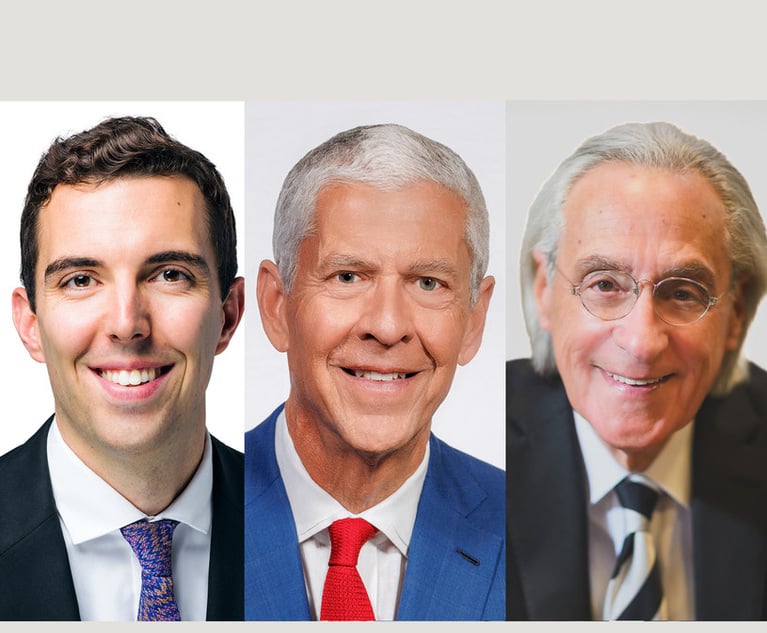

“We believe there should be full transparency, but the fact of the report, redacted or unredacted, will provide a significant foundation for claims that are not time-barred,” said Kline & Specter attorney Thomas R. Kline, who has represented numerous victims of convicted serial child molester Jerry Sandusky and is currently representing an abuse victim who testified before the grand jury that produced the recently released report.

According to Kline, regardless of the redactions, one of the most important pieces of the report for those looking to sue the church is that it helps to establish there was institutional knowledge of the abuse dating back to the 1940s. The report should also serve as a launching pad for further investigation, Kline said.

“The victims know who their abusers were,” Kline said. “We're then going to figure it out. Trust me.”

Kline said this was largely the process he used in McIlmail v. Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer, ended with the largest-ever sex abuse settlement with the Philadelphia Archdiocese. Kline declined to disclose the amount, citing the wishes of the victim's family.

“A prosecutor in Pennsylvania has wide and powerful authority to investigate and gather information in a cohesive fashion and then package it as a final product,” Kline said. “That kind of report in the McIlmail case became an in-depth starting point for litigation of an individual claim. This will happen repeatedly in claims that are not time-barred.”

However, not everyone agreed with Kline that the report would have much of an impact on litigation in Pennsylvania.

Malvern-based attorney Daniel Monahan, who represented nearly 20 plaintiffs who alleged sex abuse at the hands of priests in Philadelphia, noted that, given the statute of limitations for bringing civil suits, only a small number of claims will be potentially viable.

In Pennsylvania, victims of childhood sexual abuse have until age 30 to bring claims. Since the report documents abuse dating back to the 1940s, most of the victims are time-barred from bringing claims.

According to Monahan, in the months after the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office released a grand jury report outlining priest abuse in the Philadelphia Archdiocese in 2011, his office received about 150 calls from alleged victims. Of those victims, all but four of them were outside the statute of limitations.

Courts in Pennsylvania have been reluctant to grant exceptions to those limitations, Monahan said, noting that in 2015, the Superior Court rejected his clients' arguments that, despite the physical abuse occurring outside the statute of limitations, the psychological damages didn't manifest until years later.

Monahan also noted that, even if a case can be brought within the statute of limitations, church officials are likely to argue that they had no notice of the conduct, which would further narrow the pool of victims with viable civil claims.

“Until they open up the statute of limitations I don't see a great number of civil cases coming,” Monahan said.

Legislative Changes

Along with outlining the abuse, the report also made several recommendations to the state General Assembly regarding how sex abuse cases should be handled. One of the suggestions is to create a “civil window” that would temporarily suspend the statute of limitations so that any victim could bring a claim.

At a press conference following the release of the report, Attorney General Josh Shapiro, whose office conducted the grand jury investigation, called on state legislators to enact the recommendations.

“Stand up today, right now, and announce your support for these common-sense reforms,” Shapiro said.

Attorneys agreed that changing the statute of limitations would significantly alter the litigation landscape for victims of childhood sex abuse, and some were hopeful the report would help fuel those efforts.

“Politics are a funny thing. Politics in the U.S. and Pennsylvania are volatile, and if there's a shift in the legislature, which would happen if there was a so-called blue wave, I would expect that advocacy groups and victims, myself included, would have it high up on our agenda to open the statute of limitations to all of the victims,” Kline said.

Others were not as hopeful.

“I do think that this gives a lot of impetus, and it takes away some of the cover of legislators saying there's not a problem. When you get confronted with something as widespread as this report, I think it makes these legislators cower and think, 'What am I really protecting?'” said McLaughlin & Lauricella attorney Slade McLaughlin, who has also pursued sex abuse claims against the Philadelphia Archdiocese. ”I do think it's a powerful push, but I don't think it'll be enough.”

Curt Schroder, executive director of the Pennsylvania Coalition for Civil Justice Reform, said reviving claims already barred by the statute of limitations could also run afoul of the remedies clause in the state constitution. Instead, he noted a bill pending in the state House of Representatives that proposes extending the age for victims to bring claims from 30 to 50.

“While the past cannot be undone, Pennsylvania must now protect our children as we move forward in the aftermath of the grand jury report,” Schroder said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Kline & Specter and Bosworth Resolve Post-Settlement Fighting Ahead of Courtroom Showdown

6 minute read

'Discordant Dots': Why Phila. Zantac Judge Rejected Bid for His Recusal

3 minute read

Phila. Court System Pushed to Adapt as Justices Greenlight Changes to Pa.'s Civil Jury Selection Rules

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Courts Demonstrate Growing Willingness to Sanction Courtroom Misuse of AI

- 2The New Rules of AI: Part 1—Managing Risk

- 3Change Is Coming to the EEOC—But Not Overnight

- 4Med Mal Defense Win Stands as State Appeals Court Rejects Arguments Over Blocked Cross-Examination

- 5Rejecting 'Blind Adherence to Outdated Precedent,’ US Judge Goes His Own Way on Attorney Fees

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250