A Calm but Impressive 2018–19 Term for 'Friends of the Court'

Amici continued to play an important institutional role at the Supreme Court, and certain types of briefs got noticed more than others, a team from Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer writes in their annual review of the amicus curiae docket.

November 25, 2019 at 05:06 PM

10 minute read

Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer's offices in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy photo)

Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer's offices in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy photo)

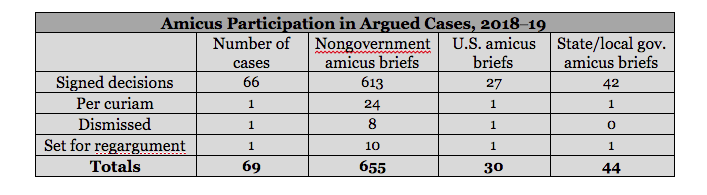

Last term, amici curiae filed more than 700 briefs, participated in 96% of argued cases, and were cited by the justices in more than half of all merits cases. Twenty years ago this would've been big news, but those numbers have become routine at One First Street. If anything, friends of the court were quieter in 2018–19 than in recent terms, which have seen a record number of briefs and the highest level of amicus participation in history.

The most notable amicus development of the term had nothing to do with the briefs themselves. The Supreme Court took steps this year to gently tighten the reins on amicus practice by announcing new word limits on friend-of-the-court briefs and issuing special guidance to address recurring issues with amicus submissions.

Still, in our ninth year analyzing the high court's amicus curiae docket for The National Law Journal, we found that amici continued to play an important institutional role at the Supreme Court, and that certain types of briefs got noticed more than others.

No Blockbuster Amicus Cases, but Still a Mountain of Briefs

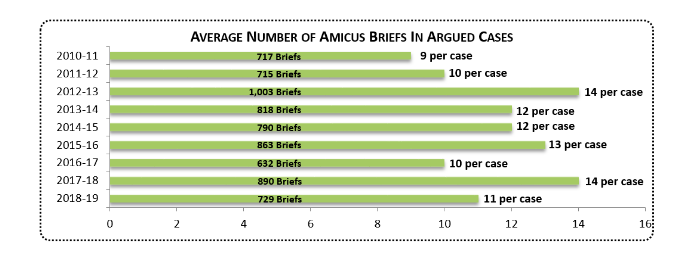

In the 2018–19 term, amici filed on average 11 briefs per case at the merits stage, down from the 2017–18 term's record 14 briefs per case. The participation rate dipped as well, with friends of the court filing briefs in 96% of argued cases, down from 100% participation in 2017–18, but within the normal participation rate from the prior eight terms, which ranged from 92 to 100%. The drop in the 2018–19 term was likely the result of fewer marquee cases that tend to attract more "friends."

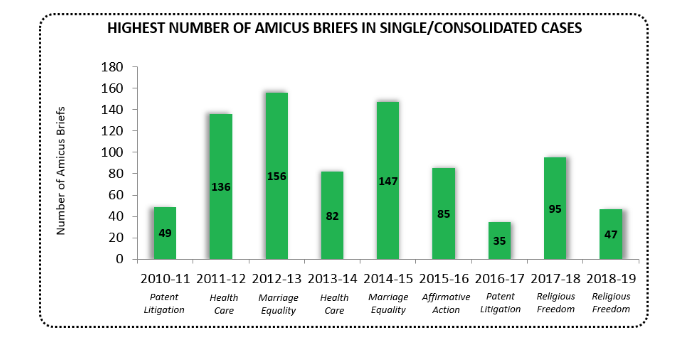

Similarly, there was a drop in the highest number of amicus briefs filed in a single or consolidated case. "Cases with 30 or more amicus briefs are no longer particularly rare, and the highest-profile cases see amicus filing reaching the triple digits," according to Aaron-Andrew P. Bruhl and Adam Feldman's "Separating the Amicus Wheat From Chaff," 106 Geo. L. J. Online 135, 135 (2017). In 2018–19, amici did not approach triple digits, with the top case having only 47 briefs.

Unsurprisingly, cases involving hot-button issues—marriage equality, health care, religious freedom, and affirmative action—generate the most briefs, though patent cases also spur significant amicus participation. In 2018–19, amici filed the most briefs in American Legion v. American Humanist Association, a case addressing whether a war memorial shaped after a Latin cross on government-owned land violated the Establishment Clause.

Citation of 'Green' and Government Briefs

In the 2018–19 term, the justices cited amicus briefs in 56% of cases with amicus participation and signed majority opinions. That's consistent with the previous eight terms where justices cited friend-of-the-court briefs in 46% to 63% of cases. The justices cited amicus briefs in 24 majority/plurality opinions, 19 dissents, 11 concurrences, and two opinions concurring or dissenting in part. These figures exclude last term's two court-appointed amici, whose submissions are more akin to party briefs.

In 2018–19, the justices cited 8.5% (52/613) of the nongovernment briefs filed in cases with signed opinions. That citation rate of "green briefs"—so-called for the color of their covers—is in line with the prior eight terms, where the justices cited between 5% and 11.9% of nongovernment briefs.

Green briefs faced some criticisms in 2018–19, with one senator arguing that the funding of nongovernmental briefs needs to be more transparent. The court's rules require disclosure of anyone who makes a monetary contribution to a brief, and the Supreme Court Clerk invoked that requirement last term to address the growing trend of amici using GoFundMe campaigns to finance briefs, requiring disclosure of the names of crowd-funding donors.

As for government amicus briefs, the justices cited 67% (18/27) of amicus briefs submitted by the Office of the Solicitor General in 2018–19, again roughly in the middle of the 44% to 81% range over the prior eight terms.

The Briefs That Got Noticed

The recurring question we get about amicus briefs is whether they really "influence" the justices. Or are they largely ignored or simply used to bolster points that the justices would have made regardless? Only the justices themselves know the answers to those questions, and the best we can do is analyze how the justices cited the briefs in their opinions.

Last term, the justices leaned decidedly toward government amici. Traditionally, the justices often cite amicus briefs filed by the Office of the Solicitor General, given the OSG's institutional credibility with the high court. That held true in 2018–19. Every justice cited an OSG brief, and many justices cited those briefs in multiple cases.

Often, the justices cited OSG briefs as confirming the government's current or traditional practices about a given policy matter, such as the government's position on immunity rules (Jam), on how U.S. embassies treat service of process (Republic of Sudan), and how the government handles confidential data from third parties (Food Marketing Institute). As in past terms, the justices also cited OSG briefs simply to note their disagreement with the government's arguments (e.g., Garza, Virginia Uranium).

Office of the Solicitor General at the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. Credit: Mike Scarcella/ NLJ

Office of the Solicitor General at the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. Credit: Mike Scarcella/ NLJOther governmental amicus briefs also drew attention last term. One justice cited a brief by Illinois and more than 30 other states that provided information on how states regulate alcohol licenses (Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers). Another justice cited a brief from Idaho and eight other states concerning how states interpret the word "title" under a federal statute (Sturgeon). And in her majority opinion in Sturgeon v. Frost, Justice Elena Kagan cited the state of Alaska's brief to clarify that the issues in the case did not disturb prior lower court decisions interpreting different provisions of the statute at issue, illustrating that sometimes amicus briefs help define and limit the scope of the high court's decision on a related question.

The justices also cited briefs from Native American tribes, including the Yakama Nation's brief for background on the tribe's negotiations of a treaty with the United States in 1855 (Cougar Den), and the Crow Tribe's brief concerning its historic relationship with the Bighorn Mountains (Herrera).

Green briefs were not as prominent in 2018–19 as in previous terms. Yet the justices still cited numerous nongovernmental amici. For instance, briefs by legal scholars made a splash. Studies show that briefs by academics get "closer attention—at least initially," according to Kelly J. Lynch, "Best Friends? Supreme Court Law Clerks on Effective Amicus Curiae Briefs," 20 J.L. & Pol. 33, 52 (2004). Despite some criticism of "scholars' briefs," see Richard H. Fallon Jr., "Scholars' Briefs and the Vocation of a Law Professor," 4 J. Legal Analysis 223 (2012), the justices in 2018–19 cited briefs submitted by scholars of contract law (Lamps Plus), administrative law (Kisor), Eighth Amendment (Timbs), and even "cemetery law" (Knick).

Other green briefs getting noticed were those containing "legislative facts"—"generalized facts about the world that are not limited to any specific case," see Allison Orr Larsen, "The Trouble With Amicus Facts," 100 Va. L. Rev. 1757, 1759 (2014). The justices cited amicus briefs providing "examples of appeal waiver" contracts (Garza), samples of contracts that could affect bankruptcy courts' approach to IP rights (Mission Product Holdings), data on immigration detentions (Nielsen), and examples of journalists arrested during public protest gatherings (Nieves). Perhaps the most heartfelt briefs cited were those submitted by veterans in American Legion expressing their views on the effect of a particular war memorial.

As in other recent terms, the justices repeatedly cited briefs that compiled statutes or judicial opinions (Lamps Plus, Gamble, Rehaif, Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers), offering the court a broader perspective on the questions presented.

And like prior terms, amici urged the court to consider issues not pressed in the lower courts. The court has in the past considered issues raised by an amicus brief in the first instance. See Franze & Anderson, "The Court's Increasing Reliance on Amicus Curiae in the Past Term," Nat. L. J., Aug. 24, 2011 (discussing examples). But in 2018–19, the justices were having none of it, rejecting state amici's request that the court overturn Illinois Brick's antitrust indirect-purchaser rule (Apple), and OSG's "novel" theory that inverse condemnation claims arise under federal law and permit federal question jurisdiction (Knick).

Finally, studies suggest that amici and advocates known for quality briefs get more attention. See Allison Orr Larsen and Neal Devins' "The Amicus Machine," 102 Va. L. Rev. 1901, 1922–23 (2016); see also Adam Feldman, "A Lot at Stake: Amicus Filers 2017/2018," Empirical SCOTUS, Jan. 16, 2018. That held true in the 2018–19 term. Amici known for strong briefs, like the ACLU and NACDL, were cited this past term. Overall, more than a third of the green briefs cited by the justices were authored by firms with specialized Supreme Court practices.

The Justices' Citation Rates

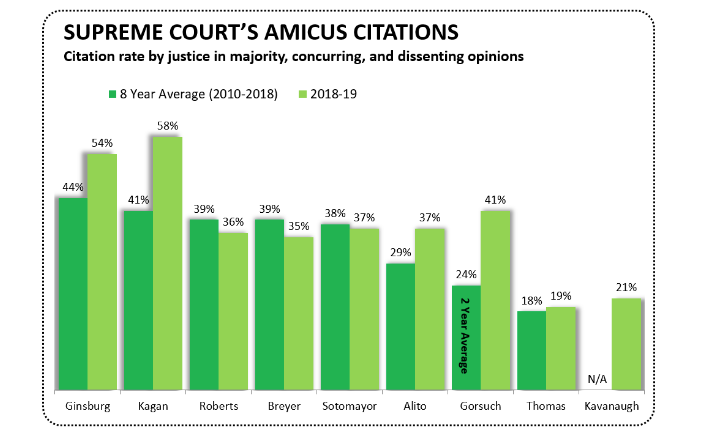

Over the previous eight terms, the justices varied substantially in how often they cited amicus briefs in their opinions. The 2018–19 term was no different, although some patterns emerge when examined under a wider lens showing the prior eight terms.

Justice Kagan and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg cited amicus briefs in the highest percentage of their opinions in 2018–19, which is in line with their prior eight-term averages. At the other end of the spectrum, Justice Clarence Thomas cited the lowest percentage of amicus briefs in his opinions in 2018–19, consistent with his eight-term average. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who in his first full term cited amicus briefs in 21% of his opinions, is a stark difference from his predecessor Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was one of the court's most prolific amicus citers. The remaining justices tend to cite briefs in around 30% to 40% of their opinions.

The 2018–19 term will not go down in the record books for amicus curiae practice. The last time amicus numbers dipped like this, the court likewise started the term with only eight justices, perhaps tempering the court's desire to decide the kinds of blockbuster issues that draw the most amicus attention. See Franze & Anderson, "In Quiet Term, a Drop in Amicus Curiae at the Supreme Court," Supreme Court Brief, Sept. 6, 2017. But 2018–19 reflects that even in a calm year, friends of the court are a mainstay in Supreme Court practice. While the justices have taken steps to shorten briefs and provide further guidance on amicus submissions, they have not imposed any new limits to stem the annual tidal wave of amicus briefs.

Love them or hate them, amici are here to stay, and the justices continue to look to their "friends" for support.

Anthony J. Franze and R. Reeves Anderson are members of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer's appellate and Supreme Court practice. The firm represented amici in several cases referenced in this article. The authors thank Kathryne Lindsey for her assistance with the compilation of data.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Supreme Court Justices Have 'Variety of Views' on Ethics, Kagan Says

Supreme Court Rejects Controversial Election Theory From GOP Lawmakers

Can Congress Tax Unrealized Gains as Income? Supreme Court May Decide

Supreme Court Brief: Water Rights Dispute | What Would an Ethics Code for Justices Look Like?

8 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 15th Circuit Considers Challenge to Louisiana's Ten Commandments Law

- 2Crocs Accused of Padding Revenue With Channel-Stuffing HEYDUDE Shoes

- 3E-discovery Practitioners Are Racing to Adapt to Social Media’s Evolving Landscape

- 4The Law Firm Disrupted: For Office Policies, Big Law Has Its Ear to the Market, Not to Trump

- 5FTC Finalizes Child Online Privacy Rule Updates, But Ferguson Eyes Further Changes

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250