The Slowpoke Report: Federal Judges in Two of Texas' Busiest Divisions Tread Water

Every year, Texas Lawyer takes a look at the number of civil cases and motions pending to check up on the federal bench around the state.

February 01, 2018 at 12:30 PM

12 minute read

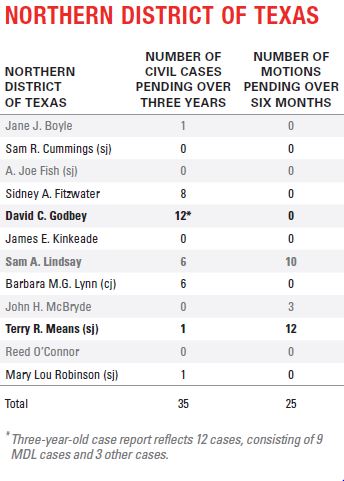

Senior U.S. District Judge Terry Means is one of three Article III judges who keep Fort Worth's busy federal courthouse humming. He's a big reason why Cowtown's lawyers are accustomed to prompt rulings and civil dockets that never get backed up.

In fact, Fort Worth's federal judiciary is so resolutely efficient that none of the three—including U.S. District Judges John McBryde and Reed O'Connor—have ever rated a mention on Texas Lawyer's Slowpoke Report in over two decades.

But 2017 was different.

Pursuant to the Civil Justice Reform Act of 1990, each year U.S. district judges and U.S. magistrate judges must disclose the number of civil cases pending in their courts for more than three years and the number of civil motions pending in their courts for more than six months. Most judges like to keep those numbers below 10 in both categories. Every year, Texas Lawyer takes a look at those numbers to check up on the federal bench around the state.

“We know about the Slowpoke list and we try to stay off of it. We do it because we want our litigants to get prompt rulings,” said Means, who took senior status in 2013 and still takes an equal share of civil and criminal cases in the Fort Worth division.

But sometimes even the most efficient judges can wind up on the report through no fault of their own. And that's exactly what happened to Means. As of Sept. 31, Means reported 12 motions pending for more than six months.

The reason for Mean's delay in moving some civil cases as unfortunate as it is understandable—he lost the assistance of a law clerk who was responsible for roughly half his docket while she was away caring for a sick child.

“Her little boy came down with a very rare disease. He almost died,” Means said. “While she was out, we didn't want to hire someone else to replace her. Over time, we hoped things would get better. And she had to leave.”

Means expects he'll be off the Slowpoke Report soon. “It took us a while for us to replace her and I'm sure we'll be done by the next reporting period,” he said.

Means wasn't the only judge on the Northern District of Texas who found himself behind on his or her work. In Dallas, U.S. District Judge Sam Lindsay reported that he had 10 motions pending for more than six months. That's half the amount of motions pending that Lindsay reported in 2016 with 20.

“I'm just working hard and getting those motions out. And so that's what happened. I hope to have none the next time you call me,” Lindsay said.

Part of the reason for the delay is the Dallas Division has been down from eight judges to six for more than two years, Lindsay said. President Donald Trump has nominated Dallas attorney Karen Gren Scholer to fill a seat vacated by U.S. District Judge Jorge Solis in 2016 but has yet to take action on another Dallas federal bench that was left empty when O'Connor transferred to the Fort Worth Division in 2013.

“All of us have had to carry a much heavier load,'' said Lindsay, who notes that none of his fellow Dallas judges like to see their names on the Slowpoke Report. “It's on the back of most of our minds. If you look at the Houston Division, there are some judges that are always on the list. You'd like to keep it in single digits but sometimes it's not possible. Sometimes the complexity of the case doesn't allow that.''

Dallas U.S. District Judge David Godbey also made the report with 12 cases pending for longer than three years. However, nine of those cases come with an asterisk—they are all part of the multidistrict litigation consisting of investors trying to recover millions of dollars from a Ponzi scheme devised by convicted financier R. Allen Stanford.

Godbey appointed a receiver to recover the millions in Ponzi scheme funds, prompting third party-defendants to challenge a number of his rulings about the manner and method of the receivership. The Stanford investor cases on his docket are now nearly nine years old.

Godbey declined to comment about the Stanford litigation. But Kevin Sadler, a partner in the Palo Alto office of Baker Botts who represents the receiver in the Stanford cases, says the litigation is moving about as quickly as could be expected.

“Given the worldwide size of Allen Stanford's Ponzi scheme and the number of people that aided, abetted or profited from his scheme and the pace of the litigation, it's not surprising,” Sadler said.

Sadler expects another three years of litigation, which could change depending on whether the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit overturns some of settlements reached in those cases.

The remaining old cases on Godbeys' docket include a death penalty habeas case that has been stayed until the prisoner exhausts his state remedies, a civil rights case that has been stayed pending appeal, and a Fair Labor Standards Act case that is set for trial in 2018.

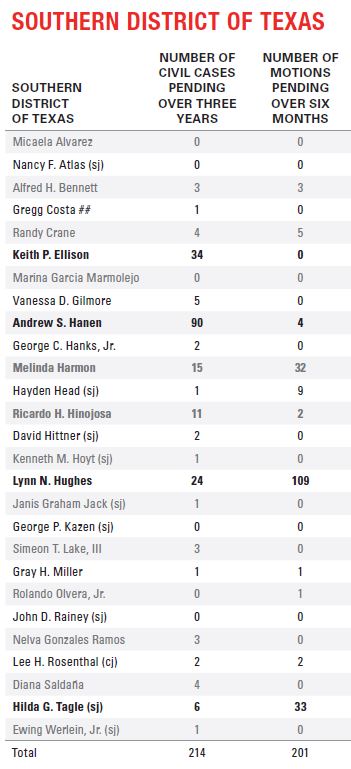

The Southern District

In Houston, there are two judges that have appeared on the Slowpoke Report every year for over a decade—U.S. District Judge Melinda Harmon and U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes. And 2017 was no exception for both judges.

Harmon reported 15 cases pending for more than three years and 32 motions pending for over six months. Hughes reported 24 cases pending for more than three years and a whopping 109 motions pending for other six months.

Harmon did not return a call for comment and Hughes declined to comment.

A veteran Houston litigator who has appeared before both Harmon and Hughes believes both judges are perennial Slowpokes for different reasons.

“Harmon is different than Hughes. She's just painfully slow,” said the lawyer, who wanted to remain anonymous to protect his clients. “And whenever you get a case assigned to her, you won't get to trial for years. She just takes a very long time.”

Part of the reason Harmon has made the list is she was still dealing with a shareholders' suit related to the financial failure of Enron more than 15 years after the energy trading company's collapse. One of those cases settled in February 2017.

With Hughes, his speed seems to be determined by how interested he is in a case, the lawyer said.

“I just thinks he finds cases that he likes and that he finds intellectually stimulating and the other cases he doesn't like and he sits on them,'' the lawyer said. “He's very bright and he works very hard. But some case he likes and some cases he doesn't like.''

Houston U.S. District Judge Keith Ellison made the Slowpoke Report primarily because of a single dispute. Ellison reported 34 cases pending for more than three years and most of them were related to multidistrict litigation filed by BP shareholders who filed class action lawsuits against the oil company in the wake of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Ellison said much of the complicated work on the BP cases has been completed, including class certifications and settlements with some of the parties.

“We've got a ton of stuff done. We've gotten all of the classes taken care of and now we have all of these individual claims,” Ellison said. “We've had three different iterations of motions to dismiss and motions to interpret English law on these claims.''

Ellison said that not all of the old cases on his docket are related to the BP case. At least two of them are federal habeas death penalty appeals that have been not moved off his docket because they have significant appellate issues and are tied up at the Fifth Circuit. Other than those cases, Ellison said his docket is current.

“There's nobody on my docket that's asking for a prompt hearing that I'm not giving them,” Ellison said. “I'm ready to go on these cases at any time.”

In Brownsville, U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen has 90 civil cases pending on his docket for more than three years—the highest total of any federal judge in the state. But all of those cases also come with the another big caveat: They're all border-fence condemnation cases.

The cases date back to 2008 when the U.S. Department of Homeland Security filed eminent domain proceedings against hundreds of Texas landowners as part of a government project to build new sections of fence along the U.S.-Mexico border. Those cases have a host of problems, including determining exactly who owns the land the government wants to condemn as some of the deed records the parties rely on date back centuries.

Hanen said the government and the land owners have done a great job in settling the cases, but there's only so much he can do when the government can't locate the correct party to condemn property.

“I didn't expect them to last this long at all. I thought we'd try a few and settle,” Hanen said. “But I didn't realize when they were filed that the real difficult part is finding the owners. I don't think anybody anticipated that.''

Brownsville Senior U.S. District Judge Hilda Tagle also made the Slowpoke Report for the 33 motions pending on her docket for more than six months. Tagle did not return a call for comment.

In McAllen, U.S. District Judge Ricardo Hinojosa reported 11 civil cases pending for more than three years. Hinojosa explained that few of those civil cases are ready for trial because lawyers have asked for continuances in those cases.

“We have a heavy criminal docket,” Hinojosa said. “When parties ask for continuances in civil cases, we tend to give them.”

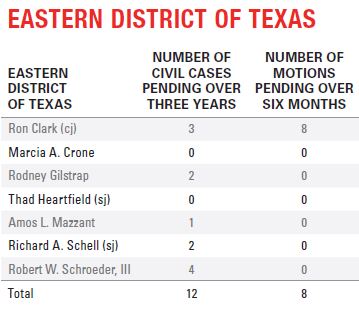

The Eastern and Western Districts

If there's a place where a judges should be expected to be behind on their work, it's the Eastern District of Texas.

Jurists there carry weighted caseloads that are double the national average at 1,000 and the district has long been operating under a “judicial emergency” as declared by the U.S. Judicial Conference because of its high caseloads and judicial vacancies.

The district, which is still one of the most popular venues in the nation for patent litigation, is currently down three judges and will add a fourth to the list in February when Eastern District Chief Judge Ron Clark takes senior status.

Yet in 2017, not one of the seven federal judges who hears cases in the Eastern District registered double digits in either Slowpoke Report category.

“It's a surprise, but good news,” Clark explains. “I think there are two reasons.

One, the judges are all working too hard. When I want to call one of the judges on the weekend, I call them at their offices. That's been going on for years,” Clark said. “And two, our magistrate judges have stepped up doing yeoman's work handling consent cases, handling motions and handling pretrial matters.''

Another reason Eastern District judges have been able to keep their heads above water is the Judicial Conference has allowed each of them to hire one additional law clerk because of the intense workload, Clark said.

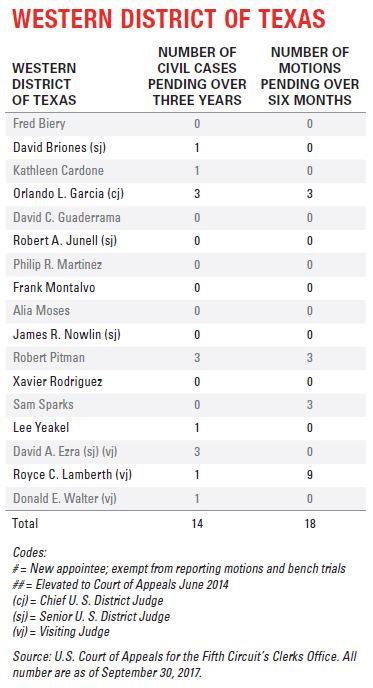

The Western District of Texas also made it through 2017 without a single judge landing on the Slowpoke Report. And much like their colleagues to the East, the Western District judges managed to keep their dockets current while operating under a judicial emergency.

The Western District, which has one of the nation's heaviest criminal dockets, currently has three vacancies in the Austin, Waco and Midland divisions. President Trump has nominated U.S. Magistrate Judge David Counts to the Midland seat and is expected to be confirmed early this year.

Orlando Garcia, chief judge of the Western District of Texas, said his colleagues have managed to keep their dockets current because they are willing to hit the road and cover for divisions that have vacant benches.

“I truly think it's a dedicated group of judges, including balancing of dockets including working as a team and covering the Waco and Midland and Pecos divisions,” Garcia said.

Some of the judges have more miles on their cars because of that teamwork, he said, but none more than U.S. District Judge Robert Pitman who handles dockets in Austin, Waco and San Antonio—cities that are all connected by the same highway.

“In the case of Judge Pitman, we refer to him as our I-35 judge,” Garcia said. “I've told him that when he finishes up Waco, we're going to have I-35 moved to Midland so he can cover that, too.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

5th Circuit Strikes Down Law Barring Handgun Sales to Adults Under 21

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

Special Counsel Jack Smith Prepares Final Report as Trump Opposes Its Release

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Munger, Gibson Dunn Billed $63 Million to Snap in 2024

- 2January Petitions Press High Court on Guns, Birth Certificate Sex Classifications

- 3'A Waste of Your Time': Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

- 4Judge Extends Tom Girardi's Time in Prison Medical Facility to Feb. 20

- 5Supreme Court Denies Trump's Request to Pause Pending Environmental Cases

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250