Cautious Optimism Over the Increasingly Prevalent Alternative Fee Arrangements

While we celebrate the innovation and look forward to working under alternative fee arrangements more often, the death knell for billable hours hasn't sounded yet.

August 01, 2018 at 12:01 AM

6 minute read

For many years, billable hours have been the default for legal billing. Due to tightened budgets and the increasing leverage of consumers of legal services following the Great Recession, alternative fee arrangements have become more common. While we celebrate the innovation and look forward to working under alternative fee arrangements more often, the death knell for billable hours hasn't sounded yet.

The Problem With Billables

The billable hour did not rise in prominence until the 1960s due to the convergence of two factors: the birth of large law firms and computerized methods of timekeeping. On the former, consider these statistics: In 1951, there were about 220,000 lawyers, as compared to around 1.4 million now. Similarly, during the late 1950s, fewer than 40 firms had more than 50 lawyers; in 2016, more than 350 firms had more than 100 lawyers. This growth is the result of a straightforward profitability calculus: Firm revenue increase with more associates rather than raising existing attorneys' rates.

Billable hours, unlike many previous billing arrangements, aim for a more objective measure: to capture and bill all time spent on a matter. Billable hours also led to some gross abuses: attorneys at a prominent firm who billed an average of more than 16 hours a day for more than four years (an average of 5,941 hours per year); an attorney who billed 96 hours in a single day; an attorney who sought—and received—firm approval to routinely increase a particular client's bills by 15 percent; and the attorney who logged 13,000 hours in 13 months.

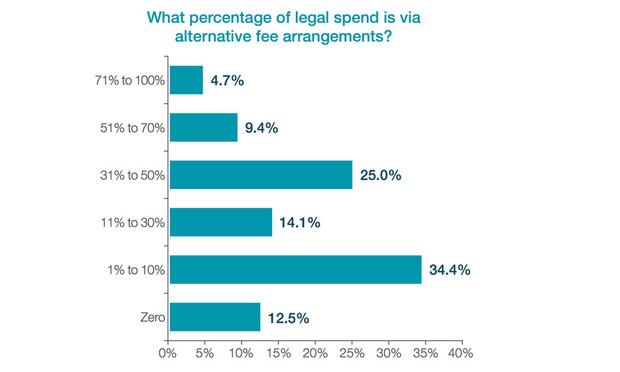

(Courtesy of Blickstein Group/Consilio)

(Courtesy of Blickstein Group/Consilio)These dishonesties exacerbate negative preconceptions of lawyers. A survey in the 1990s revealed that almost half of CEOs and in-house counsel believe that outside counsel's bills are inflated. Although certainly less of a concern for clients, billable hours are also reviled by lawyers. Lawyers have worked increasingly long hours since billable hours came the predominate billing arrangement. The billable hour is the chief complaint amongst lawyers; stress, fatigue and depression are all correlated with lawyers' longer workdays.

Necessity as the Mother of Invention: The Great Recession and Rise of AFAs

The Great Recession squeezed the budgets of clients and resulted in a marked shift away from the billable hour. For example, just from 2008 to 2009, the number of legal departments reporting that they spend more than 10 percent of total fees on nonhourly arrangements increased from 27 percent to 43 percent. In 2016, AFAs were roughly a quarter of the approximately $21 billion spent on outside legal fees.

A survey of more than 350 law firms confirms the shift. Almost all (97 percent) worked under AFAs for at least some matters. Nearly three-quarters of these firms admitted a reactive posture, willing to work under AFAs only at the client's suggestion. Interestingly, a firm's willingness to proactively pitch AFAs is correlated with the profitability of the arrangement—85 percent of proactive firms were at least as profitable with AFAs as billable hours, while this was true for only 51 percent of the reactive firms.

Clients shifting to AFAs are happy with the results and are looking for ways to shift more legal expenses to AFAs. Each year, Norton Rose Fullbright publishes a report on litigation trends. In 2017, the report included results from a survey of more than 330 senior corporate counsel. Of this group, more than half used AFAs and these accounted for 28 percent of the group's entire legal spend. Nearly all were satisfied with AFAs. For most corporate clients, AFAs make up a small percentage of their entire legal spend.

While it is hard to find many dissenting voices to the trend toward AFAs, some commentators argue that the emphasis on AFAs is somewhat misplaced. Budgets, imposed on litigation and transactional matters, are far more common; these two—AFAs and budget-based matters—account for between 80 and 90 percent of law firm revenues.

Practical Considerations for and Limitations of AFAs

From an in-house counsel standpoint, the AFAs provided some level of certainty as to annual legal budget spend. Not all cases were initially suitable for AFAs, particularly not those involving very complex litigation issues and transactional issues. The AFAs were only envisioned as encompassing case work-up and preparation to the trial phase. It was quickly realized that trials were unique and unlikely to fit into an estimate anticipated legal cost—as a result it was eventually excluded from the AFAs' ambit.

From the private practitioner standpoint, AFAs were initially generally viewed with some amount of skepticism. Depending on how a firm reports billing under an AFA, the benefit of minimized billing is one of the greatest advantages when managing a high case volume client. The hours saved by not having to revise time entries, cut time, review audits, send out bills, etc. is a game-changer. There should be a mutual financial benefit for both the firm and the client. The financial benefit to the firm is arguably greater if the flat fee is managed efficiently. Knowing when and how much the firm is being paid on a long-term basis is critical to any firm from the standpoint of management of the firm's finances.

AFAs are no longer an outlier, and we expect a growing proportionate billing share in the coming years. We celebrate the trend and look forward to firms and clients finding ever-more creative ways of handling legal needs.

Ed Slaughter is partner-in-charge of the Dallas office of Hawkins Parnell Thackston & Young. He has been a trial lawyer for more than 20 years representing corporations and individuals in high risk litigation.

Chris Collier is deputy partner-in-charge of the Atlanta office of Hawkins Parnell Thackston & Young. His practices areas include premises liability, product liability, toxic tort, transportation and general negligence.

Michael Arndt is an associate for Hawkins Parnell Thackston & Young, where he defends corporations and premises owners in high-risk litigation.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Nondisparagement Clauses in Divorce: Balancing Family Harmony and Free Speech

6 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise, Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

- 2Latest Boutique Combination in Florida Continues Am Law 200 Merger Activity

- 3Sarno da Costa D’Aniello Maceri LLC Announces Addition of New Office in Eatontown, NJ, and Named Partner

- 4Friday Newspaper

- 5Public Notices/Calendars

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250