Uncovering a Mystery: Who Were the First African-American Attorneys in Texas?

It might be hard to believe, but until relatively recently there was some disagreement on who, exactly, the first African-American attorneys were in Texas. Once you know the story, however, it becomes a little more clear why that mystery existed. In an interview with Texas Lawyer, Dallas shareholder John Browning of Passman & Jones explains.

February 26, 2019 at 01:04 PM

14 minute read

An illustration from a contemporary newspaper of W.A. Price after he moved to Kansas (where he won a landmark civil rights case before the Kansas Supreme Court in 1891 that helped form the precedent for Brown v. Board).

An illustration from a contemporary newspaper of W.A. Price after he moved to Kansas (where he won a landmark civil rights case before the Kansas Supreme Court in 1891 that helped form the precedent for Brown v. Board).

It might be hard to believe, but until relatively recently there was some disagreement on who, exactly, the first African-American attorneys were in Texas. Once you know the story, however, it becomes a little more clear why that remained such a mystery. Those trailblazers who overcame racist barriers to practice law weren't celebrated for their achievements, except in newspapers and publications created specifically to cater to the African-American community. If any reference appeared at all in mainstream newspapers, it was usually to call attention to the novelty of it all.

“'Imagine! A colored attorney, prepare yourselves to be shocked when you enter the courtroom!' kind of things,” said John Browning, a shareholder at Passman & Jones in Dallas.

Browning, over the last seven years or so, has set out to uncover and document that history that to this point has remained obscured from a dearth of information caused by various government leaders who would've preferred to bury the accomplishments of these earliest African-American attorneys in Texas. Browning and Carolyn Wright—former chief justice of the Fifth Court of Appeals of Texas—have co-authored research papers and given joint presentations on the history they have unearthed.

Browning recently spoke with Texas Lawyer about how he started doing this research, what he's found and the importance of this history. The interview below has been edited for length and clarity.

Texas Lawyer: How long have you been researching and writing on the history of early black lawyers in Texas?

John G. Browning of Passman & Jones in Texas.

John G. Browning of Passman & Jones in Texas.John Browning: Probably about 2012, 2013. You know the impetus for this was reading in the Texas Bar Journal. They had a special issue that was built around the tagline, “We Were First,” and it had things like first Asian-American judge in Texas. The first African-American female federal judge. Things like that—trailblazers and milestones honoring the diversity in our profession. But what struck me was the fact that there was some serious uncertainty and no clear answer on who was the first African-American lawyer admitted to practice in Texas. We know the first African-American female Charlye O. Farris because that was comparatively recent. It was, I think, 1953 or 1954. And so going back considerably further in our history, to Reconstruction days, you encounter a whole lot of difficulty, not just because of the scarcity of records but also various other factors including historians maybe overlooking this stuff.

TL: What was the biggest lift early on? How did you cobble this together? How did you approach it, and then what were your early findings?

JB: Well, I found that there was some confusion among historians over who was actually the first. There were two gentlemen not too far apart in time. William A. Price from the Fort Bend Country area, and A.W. Wilder, from Brennan. And Mr. Wilder, we know a little bit more because he was one of the first African-Americans to serve in the Texas Legislature, but he oftentimes is mistakenly referred to as the first. Whereas W.A .Price was actually several years ahead of him in terms of being admitted to practice.

We found things like historians misidentifying Price as William B. Price, which is actually the name of a military figure for Texas history, who wound up serving for the Confederate army, so clearly a big disconnect there. But we also saw a lack of information in part because of the often-scattered mentions of these figures. They might be mentioned in contemporary newspapers that catered to the African-American communities in Texas, but often would not be mentioned in the mainstream white newspapers. And if they were, sometimes they were as a novelty. Like, “Imagine! A colored attorney, prepare yourselves to be shocked when you enter the courtroom!” kind of things. Or, there were stories that were derogatory, expressing fairly racist descriptions of the lawyers or how they handled themselves.

TL: Trying to uncover sources and the like for historical research is difficult as it is, and I imagine doubly so for any black history that goes back that far. Did you encounter any kind of barriers like what you mentioned earlier, a dearth of information today, but was there a dearth of firsthand sourcing that was problematic for you?

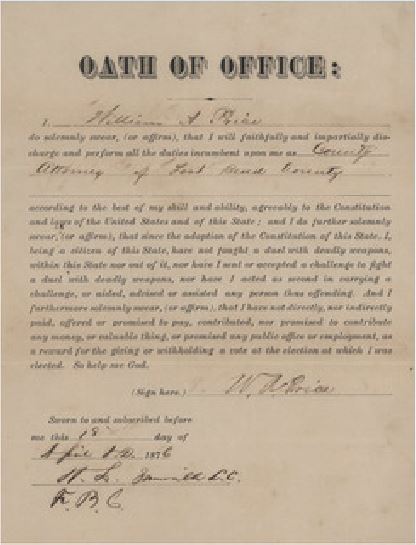

JB: Oh sure, yeah, very much so. In fact, I don't know how to describe it—maybe as whitewashing or as simple error, but some of the official records just completely omitted mentions of black attorneys. For example, Fort Bend County has an online listing, detailing year by year, term by term, identifying every elected official in that county. So you can tell who's held the office of county judge ever since the county's been in existence. And in looking at their official online listing, I found a complete omission of W.A. Price, who was elected as county attorney and held that office, starting in 1876. I mean I actually found his oath of office, I found election results. I found contemporary newspaper accounts referencing both the campaign and his election and service. I even found records in his own handwriting, because obviously they didn't have word processors. We can dissect his handwritten indictments and things like that. So I wrote to the Fort Bend County historical commission, pointed out the omission, gave them a wealth of documentary evidence, and that's since been cleared up. But I would find things like that.

A digital image from the rolls of the Supreme Court of Texas, reflecting the admission in February 1883 of John N. Johnson, the first African-American admitted to practice before the Supreme Court (and also Austin's first African-American lawyer).

A digital image from the rolls of the Supreme Court of Texas, reflecting the admission in February 1883 of John N. Johnson, the first African-American admitted to practice before the Supreme Court (and also Austin's first African-American lawyer).And another county involving one of the first—in fact, the first—African-American to practice before the Supreme Court of Texas, a man named John N. Johnson, who was the first black lawyer in Austin. I found in the historical collections in Brazos County where he was initially admitted to practice, I found records substantiating his two previous applications to practice law and their rejection of him. This was at a time, by the way, when it was ridiculously easy to become a member of the Texas bar. John Wesley Hardin, the notorious outlaw, was a Texas lawyer. We didn't have a bar exam; we had a very loosey goosey type of system. And yet African-American attorneys disproportionately encountered more difficulty. In looking at the records for that particular attorney, I found evidence of them denying him admission. But conspicuously absent in terms of what they preserved, was his actual successful application and the issuance of his license to practice.

TL: So you feel confident in asserting that W.A. Price was the first black attorney to practice in Texas?

JB: Oh yes, in fact, he occupies some unique stature in the annals of Texas law. He was absolutely the first African-American admitted to practice in Texas, and that was in 1873. We got the documentation of that. He also was the first African-American to hold judicial office. And we found evidence, not only through contemporary newspaper references, publications of judgments issued when he was a justice of the peace in Matagorda County in 1872, but we actually found documentation of his filing the required bond for people holding that kind of judicial office in 1871. And of course, then as now, you didn't have to have a law degree or be a lawyer to be a JP, so he was a JP and he became a lawyer, and then in 1876 he ran in Fort Bend County for the office of county attorney, which was essentially the equivalent of district attorney. So we know that he was the first in these three categories: first lawyer, first judge, first county or district attorney.

TL: You mentioned some whitewashing in the past that made it difficult to turn up some information. As you're educating folks on the past, have you encountered any resistance to people learning the history now that we know it?

JB: No, actually, people have been very receptive. A lot of the groups that show the greatest interest in hearing about this either tend to be groups in the African-American community. A lot of which, by the way, they have their beginnings in our segregated past. But a lot of these audiences, including the Dallas Bar of Legal History section, I've had a wonderful reception, and there's been a great deal of interest in this.

TL: It's pretty self-evident why those associations would take interest in this. Why is it important to know this information, in general? If you're a practicing attorney, regardless of your racial background, why is it important to know this history?

JB: Well, because these are lawyers who blazed a trail, who made it possible for the ones that follow. We wouldn't have had the Eric Holders, for example, without having the Thurgood Marshalls. We wouldn't have had the Thurgood Marshalls without having had countless other professional forebears. And lawyers today, whether you are in the African-American community or not, we stand on the shoulders of the lawyers who have gone before us. And recognizing the contributions of lawyers like these early African-American lawyers in Texas, is important, because we're now in 2019, a year that marks the 400th anniversary of enslaved African-American people being brought to the Jamestown Colony. While it may seem like, gosh, this is in the past, why are we still talking about this, you need to look no further than current events and the leadership crisis going on in the state of Virginia to see that there are painful lessons from our past that are still very much a part of the national discussion. We still struggle in our own profession with achieving goals when it comes to diversity, and it's important for people to know who came before us and what they did. And not only what they did, but under what kind of circumstances. These first African-American lawyers, people like W.A. Price, for example, were practicing at a time when not only was it a novelty that was commented on, but just the mere status of being an African-American who dared to strive for and achieve the upward mobility of entering the legal profession, was something that could get you attacked. A number of African-American attorneys throughout the South were attacked, and in some cases killed or lynched. They were leaders in their community. Many of the early African-American lawyers were also people who taught, who were active politically, running for office or participating in the political process. They wrote. Several of them started newspapers. W.A. Price did; John N. Johnson did. And they did all this. They made these kind of contributions at a time when blacks were routinely restricted from serving on juries. When they would walk into courtrooms where they were at a distinct disadvantage. Where their opposing counsel and even the judge would not address them with the kind of respect befitting their status as attorneys. They were referred to in more demeaning terms by their first name or as “boy.” These were attorneys who could not and their clients couldn't use the facilities at the courthouses where they practiced because they were whites-only.

These sort of obstacles that they overcame didn't prevent them from doing things like filing the earliest civil rights lawsuits in Texas and pushing for change. There were these young black lawyers, particularly in the case of John Johnson, who would write editorials speaking out against issues that resonate even today. Things like the exclusion of blacks from juries. The deaths of black men in police custody. Inequality in educational opportunities. And of course racial violence like lynchings.

TL: The practice of law is difficult enough without all those barriers thrown into the mix.

JB: Yeah, exactly.

TL: Is there anything else that you would like people to know?

JB: Just that a lot of this is still ongoing. As some of my work gets better known, I've had people reach out to me. For example, the school house—what was the segregated, what we would call the colored school in Bryan, Texas—the building that housed that, where John N. Johnson actually taught school before and after becoming a lawyer, now houses an African-American history museum. And people there in the Brazos County area have reached out to provide additional details about some of the history. It's very much an ongoing process. There's a lot yet to uncover. And it's something I continue to work on.

TL: Is there anyone else that as you've been doing this research who's been particularly instrumental in helping?

JB: Absolutely! My good friend and distinguished co-author on quite a number of my articles, former Chief Justice Carolyn Wright. She's now retired as of the end of 2018 from her service on the Fifth Court of Appeals. She has been instrumental in all of this—in fact, she and I have spoken jointly, making presentations to various groups. We've co-authored articles. It's really a kind of unique working relationship because, as I joke, I'm just a guy who writes about history, but Chief Justice Wright has literally made history. She was the first African-American elected to a multicounty office in the state of Texas. First African-American woman to be chief justice of an intermediate appellate court. Someone who has blazed trails herself, she has lent unique insight into so many aspects of this. It's impossible to categorize every single way, one of the things I know she suggested early on about looking into some of the sources of support, was looking into the role that the African-American Episcopal churches played in supporting and educating these original lawyers. And that's just one thing, but she's been tremendous. In fact, Chief Justice Wright and I were honored with the state bar's highest award, the President's Certificate of Merit, just a couple years ago at the state bar annual meeting for our work in bringing this issue some attention and building awareness about it.

And in addition I've benefited from research help from a friend and professional genealogist. She's actually a published scholar herself, a woman named Ronda McAllen, and she has helped tremendously in tracking down some of these early figures, particularly what happens when we're not seeing references to them in contemporary newspapers or pleadings that we may find in courthouses. She's assisted with building kind of a genealogy on several of them.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

US Patent Innovators Can Look to International Trade Commission Enforcement for Protection, IP Lawyers Say

How Uncertainty in College Athletics Compensation Could Drive Lawsuits in 2025

Vinson & Elkins' Veteran Pro Bono Counsel on How Needs Could Change After the Election

7 minute read

Campaign for Judge: 2 San Antonio Justices Compete for Same Seat in Election

7 minute readTrending Stories

- 1How Alzheimer’s and Other Cognitive Diseases Affect Guardianship, POAs and Estate Planning

- 2How Lower Courts Are Interpreting Justices' Decision in 'Muldrow v. City of St. Louis'

- 3Phantom Income/Retained Earnings and the Potential for Inflated Support

- 4Should a Financially Dependent Child Who Rejects One Parent Still Be Emancipated?

- 5Advising Clients on Special Needs Trusts

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250