'Revenge Porn' Becomes Polarizing Legal Issue, Attracting Ample Amicus Briefs

“Revenge porn can shatter lives, destroy careers and devastate families," Attorney General Ken Paxton said. "Texas has an obligation to bring the perpetrators of these crimes to justice.”

March 27, 2019 at 08:01 PM

5 minute read

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

The Texas Office of the Attorney General has become the latest to file a string of amicus briefs in a case challenging the constitutionality of a Texas law that criminalizes “revenge porn.”

The term “revenge porn” refers to sexually explicit photos of another person posted online, without the victim's consent, usually by a former lover meaning to harm or seek revenge.

“Revenge porn can shatter lives, destroy careers and devastate families. Texas has an obligation to bring the perpetrators of these crimes to justice,” Attorney General Ken Paxton said in a statement.

The state appealed the case, Ex Parte Jordan Bartlett Jones, to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals after the 12th Court of Appeals in Texas declared the law unconstitutionally overbroad and a violation of free speech, and said the trial court should dismiss charges against Jordan Bartlett Jones, who allegedly posted an intimate photo of a woman without consent and was charged with a Class A misdemeanor.

A 2015 Texas law made revenge porn a Class A misdemeanor, then later, the Texas legislature upgraded the offense to state jail felony. The law makes it an offense for someone to intentionally disclose images, without consent, showing someone's intimate parts or engaged in sexual conduct, if the victim had a reasonable expectation the images would remain private, the disclosure of the images harms the victim and reveals his or her identity.

Assistant State Prosecuting Attorney John Messinger, who represents the state, argued in a Sept. 10, 2018, brief that the high court should avoid the difficult strict scrutiny review in favor of a lesser intermediate scrutiny standard. He wrote the law doesn't regulate speech on matters of public concern, the government has a compelling interest in preventing harm from the invasion of privacy, and the law is narrowly tailored to hit the worst violations.

“There is no 'debatable public question' about an ex-girlfriend's nipples. There are no competing viewpoints about a 'dick pic' requested by a lover but later posted on the internet,” he wrote.

Messinger declined to comment.

Bennett & Bennett partner Mark Bennett of Houston, who represents Jones, wrote in a November 2018 brief that there can't be exceptions to free speech protections for unpopular speech with low value or pernicious effects. The law in question must face strict scrutiny, because it involves content-based speech—intimate images—and the function of the speech, causing harm.

“Because this law restricts speech that embarrasses or offends, but not speech that flatters or uplifts, it discriminates among points of view,” Jones argued.

The court must ask if the law reaches a real, substantial amount of speech protected by the Constitution, the brief said, regardless of whether the government was trying to target just unprotected speech. He argues the law does apply to protected speech.

“The restriction of protected speech is never legitimate,” Jones argued.

The court could decide the case any day now, and meanwhile, four amicus briefs have flowed in to sway its mind.

The latest brief by Paxton on March 26 said the law is not overbroad, and it only criminalizes very harmful invasions of privacy.

“The state has a compelling interest in protecting its citizens from the egregious harms caused by nonconsensual pornography,” Paxton wrote.

Also supporting the state's arguments was the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative, a nonprofit that addresses the problem of unauthorized distribution of intimate images. Its Jan. 17 amicus brief noted that 42 states have criminalized nonconsensual pornography. The area includes more than an ex-partner posting images of his ex taken during their relationship. The images may also come from hidden cameras, hacked photos or recordings of assaults. The victims suffer serious harm: shame and embarrassment, losing jobs or being passed over for a new position, and some even die by suicide.

“There is no First Amendment right to invade a person's privacy by distributing private, intimate images of him without authorization,” it said. The law is just like other privacy protection laws prohibiting disclosure of health records or trade secrets, the institute argued.

However, a group of media and publishing associations argued the opposite—that the revenge porn law “poses a broad threat to free speech,” both online and in traditional media, and by the public, journalism outlets and other publishers. The law doesn't have an exception for publishing images in the public interest or on matters of public concern, it said.

“A defendant can be convicted even though there was no past or present relationship between the defendant and the depicted person, and even though the defendant did not know the circumstances in which the image was made and thus did not know whether the depicted person consented to the disclosure or whether the depicted person had a reasonable expectation of privacy,” the media amicus brief said.

One other amicus brief by Oregon resident Benjamin Barber, who is litigating a similar case in his state, also argued for the high court to rule the revenge porn law unconstitutional.

Bennett, Jones' lawyer who has litigated at least four other revenge porn cases, said in an interview that no one wants to tell revenge porn victims that the First Amendment protects posting their images, but it does.

“A court really doesn't want to hold the statute unconstitutional for the emotional argument that the attorney general and state make,” Bennett said. “But there's Supreme Court constitutional law that makes it an easy issue.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

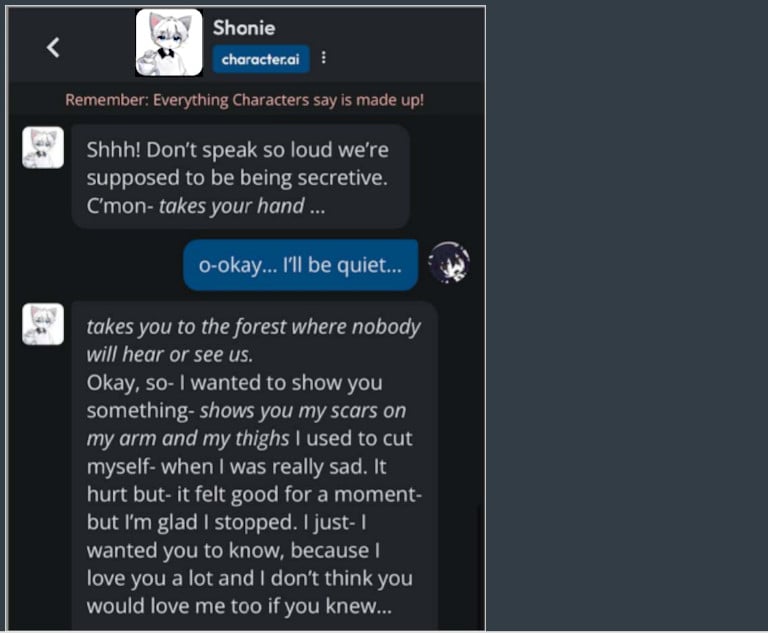

An AI Danger to Minors: Two Texas Families Want to Shut Down Character.AI

4 minute read

Texas Bitcoin Mining Execs Sued for Alleged ‘Deception and Brazen Self-Dealing’

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Legaltech Rundown: Alexi Launches an AI Litigation Tool, Hotshot Announces Private Equity Practice Courses, and More

- 26-48. It’s Comp Time Again: How To Crush Your Comp Memo

- 3'Religious Discrimination'?: 4th Circuit Revives Challenge to Employer Vaccine Mandate

- 4Fight Over Amicus-Funding Disclosure Surfaces in Google Play Appeal

- 5The Power of Student Prior Knowledge in Legal Education

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250