Grief, Depression, and a Life Cut Short

Therapist James Dolan says that if you are troubled and honestly ask for help, you have initiated the process of healing and seeing things a different way.

January 23, 2020 at 05:55 PM

6 minute read

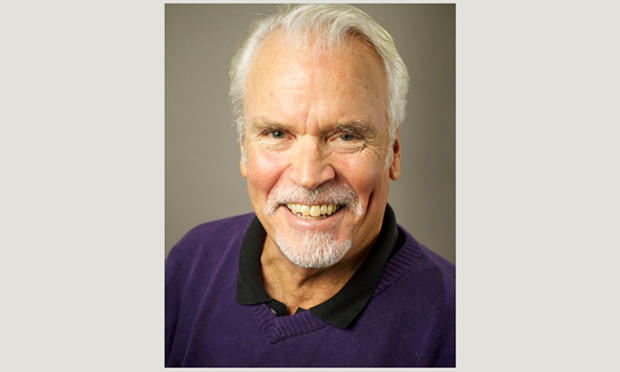

James Dolan, MA, LPC, psychotherapist, executive coach. (courtesy photo)

James Dolan, MA, LPC, psychotherapist, executive coach. (courtesy photo)

This column will be about grief, depression, and a life cut short. Stop right here if this is a turnoff, but the grief is mine, the depression was my brother's, as was the life too short.

I will not name him, but will say he practiced plaintiff law solo in a southwestern state for 35 plus years. He died of cancer last June, four years after an initial diagnosis. He was treated into remission, which lasted for about three years, but then the cancer came back with a vengeance in 2018 and he was gone by June 2019, having been age 65 for just over a month. He left a wife of 32 years and two daughters in their 20s.

I always made it a point to spend as much time with him as I could. We grew up in a single-parent home, were latchkey kids together, and shared a bond of survival many from such backgrounds have.

We often talked about his cases. My brother took on many that others would stamp "no hope" in a second. He once sued a municipality on behalf of a hooker who caught her foot in the door of a bus as she stepped off and was dragged a block or more. It took him close to 10 years to get a settlement, which came to about $30,000. Readers will perhaps mutter to themselves, "That was stupid," but be assured, my brother was not stupid. He had a rebel spirit and enjoyed striking blows against the empire when his professional life allowed it.

There were big wins, too, but never the life-changing settlement that would allow him to be the super provider he saw many of his peers become. He simply provided a good life for his family. He did it one settlement at a time, grinding it out, like a man escaping a burning building every day for 35 years.

Having never become "rich," he saw himself as a failure, and over time resignation and bitterness took root in his soul. He was depressed, but he never discussed it. He grew increasingly alienated from his wife, as that relationship was where I think he experienced his greatest sense of failure. He imagined that it was his obligation to provide her with a lifestyle that included a large modern home, frequent travel, fashionable clothes, and a circle of women friends to lunch with. When she mentioned how beautiful a friend's new home in the mountains was, he couldn't hear anything but a complaint about his failure as a provider.

His depression grew deeper. Constant stratospheric levels of stress led to an autoimmune disorder. Then the bomb blast of a Stage 4 cancer diagnosis in 2015. Even before that, a friend observed that he'd "lost his glimmer." Well said, as he was noted from early childhood as a quick wit and talented musician, but he never believed in himself enough to do anything with it. That wit became tinged with bitterness as he felt increasingly at odds with this modern world of ours. He hated the "billboard lawyers" and the constant need for aggressive self-promotion. A favorite saying of his, spoken with dark gallows glee, was that "life is a parade of shattered dreams and broken promises."

Seeing the bitterness and depression, the complaints about his wife, I suggested to him that he find a therapist. He, like so many lawyers do, responded with derision, as if I'd suggested he visit a witch doctor. His wife finally succeeded in getting him to see a well-known therapist in their town. I think he went with a predetermination that "it won't work," but went so he could say he checked the box. His description of the session was not unlike how he might have described a colonoscopy without benefit of anesthesia. I knew he'd never go back, and I saw that he took weird pride in once again having escaped facing his demons.

I am writing this now during a bout of grief that has come up six months after his death. Grief runs in channels completely out of touch with time and the conscious mind. It is not so much the holidays bringing it on as the fact that many of my visits to his city were in late fall/winter, to escape the heat. Social media is bringing up one photo memory after another from the many trips and hikes we did together over the years.

In his last days, he told a mutual friend that he realized he'd chosen the wrong profession, he hated it but it was a wheel he couldn't get off of. His refusal to get help with his depression and his broken marriage makes me so very sad. I have worked with and helped many like him, but with him I was powerless to do anything but listen, love, and keep our relationship alive. I honestly believe he would be alive today if he had lowered his walls and gotten help. He was like the Spartan boy who hid the fox in his cloak, but died when the fox ate its way out.

I miss the hell out of him.

I wonder if any reader either knows, or perhaps is, someone like my brother, someone who has something eating him from the inside, but is too embarrassed to open the cloak and say, "I need help?"

I write this today because I know there are many, many out there like my brother who suffer on, secure in the weird pride of never asking for help.

Please know that as soon as you honestly ask for help, you have initiated the process of healing and seeing things a different way. Maybe you didn't "choose the wrong profession" so much as you adopted a way of going about it that is wrong. It is enough to make a good living, to have meaningful activities other than being a lawyer. There is no need to get rich; it's enough to let enough be enough. Were any lawyer's last words ever, "I wish I'd worked harder?"

Please, think about this, and if so moved, share your thoughts.

James Dolan is a therapist and coach whose expertise is helping lawyers with depression, burnout, and conflicts at home and at work. He can be reached at www.jimdolantherapy.com or 214-629-6315.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

More Young Lawyers Are Entering Big Law With Mental Health Issues. Are Firms Ready to Accommodate Them?

Trending Stories

- 1No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 2Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 3Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 4Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

- 5Freshfields Hires Ex-SEC Corporate Finance Director in Silicon Valley

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250