Intellectual Property Audits Essential to Protecting Companies' Key Assets

Intellectual property attorneys advocate for routine, periodic, deep-dive IP audits for any company whose business is based on significant intellectual…

February 19, 2020 at 03:08 PM

6 minute read

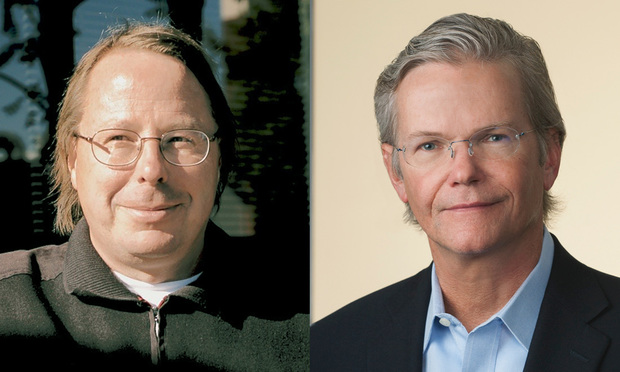

Donald Verplancken and Bruce Patterson, attorneys at Patterson + Sheridan.

Donald Verplancken and Bruce Patterson, attorneys at Patterson + Sheridan.

Intellectual property attorneys advocate for routine, periodic, deep-dive IP audits for any company whose business is based on significant intellectual property. But there are certain times in the life of a company when a meticulous, close-up analysis of the company's IP portfolio is not an optional exercise but is absolutely essential:

- The company, or a portion of it, or a major asset, is being sold.

- The company is seeking new financing or going public.

- The company is buying another business. (In this case, the primary objective will be to audit the intellectual property of the prospective purchase.)

- There has been a major turnover event, such as a change in management or the departure of key staff.

- The company has received a demand letter on behalf of a competitor challenging a key patent or patents.

Obviously, one of the first tasks of the auditing team will be to closely examine all the intellectual property held by the company, including patents, trademarks and trade secrets. Have maintenance fees—which increase with time–been maintained on all important patents, including international patents, which are often particularly expensive to maintain? Do the patents in place match the products actually being sold?

An examination of third-party patents might be required to make sure that the company's product offerings are not unknowingly infringing on patents of competitors. Are the company's important brands/trademarks protected with a registration in the US and any other important sales territory? Are all of the trademark renewals up-to-date?

Sometimes IP auditors will discover that, in the process of doing business, a successful product has been further developed or put to a new use that is no longer covered by the existing patent. A patent that doesn't cover the products of the owner is of questionable value. Or perhaps an important patent has been filed but has not yet been published, making it unavailable for examination as part of an audit.

The IP auditor must "get under the hood," in old-style parlance, to fully understand each patent and the technical aspects it protects. If the auditor is dealing with a Fortune 500 company, he or she will probably want to liaison less with the vice-president of engineering, and more with the engineers who work every day directly with the products. A direct knowledge of the nuts and bolts of each patent is more useful than the aerial or panoramic view from the top. Similarly, an in-depth discussion with marketing personnel will expose trademarks that have slipped through the cracks without being protected by a federal registration, thus adequately protecting the goodwill developed in the mark.

But an IP audit entails much, much more than simply examining patents and other intellectual property. The audit team will also spend a lot of time reviewing contracts—identifying, for example, who actually owns what has been developed on behalf of the company by examining nondisclosure agreements, development agreements, and employment, work-made-for-hire and sales contracts. Is the company's ownership of its essential IP assets secure, or have the rights inadvertently been given away or shared with a third party?

In certain countries, like Germany, patent rights entail programs to compensate the inventors. These programs may not require a large expenditure, but they still need to be kept up-to-date to maintain rights in the patent.

Contracts with vendors also need to be closely reviewed—especially those that pertain to the use of software. If the company has been using open source code, what licenses apply and do changes or additions to the code made by the company violate any of these licenses? Sometimes technicians have added code from another source to the existing code. If the technicians have departed, only a close forensic analysis of the software may uncover the problem. What if the company has been selling this revised software without being protected by a tidy trail of the necessary license agreements?

If the company is in the process of making an acquisition, the IP audit of the company being purchased may uncover issues with patents that don't match the technology of the products being sold or patents on which maintenance fees have not been kept current. Some of these problems may be fixable; others may not. The audit may actually save the acquiring company a substantial amount on the cost of the acquisition by forcing a revision in the valuation of the prospective purchase.

Here is one example of an instance in which an IP audit proved its value: an oilfield services company had grown rapidly and acquired many smaller tool companies over a short period of time. The result was the company was now holding a mixed bag of miscellaneous domestic and international patents, and no one knew exactly what they had. Worse still, the ownership of the intellectual property, including the company's important brands, had never been brought up-to-date in the various relevant patent offices.

The essential task was to examine all of these assets and try to determine which ones were relevant and complementary to the acquiring company's product lines and sales goals, and which ones should be allowed to lapse. By streamlining the overall IP portfolio and comparing the rights to current product offerings, the company was able to substantially cut costs, focus on the most promising and protected technology, and more easily identify infringers, as well as the company's possible infringement of the rights of others.

Whatever the cost of the audit—which will vary depending on the complexity of the project—it is likely to more than pay for itself, either in terms of reducing the company's IP costs through increased efficiency, achieving a more accurate valuation of a potential acquisition, or discovering opportunities for lucrative enforcement and/or licensing agreements.

Donald Verplancken is a partner in the Houston office of the IP boutique law firm Patterson + Sheridan, with special expertise in transactional matters and in the areas of manufacturing, technology, semiconductor devices and process equipment, and electronics. Bruce Patterson is also a partner in the Houston office of Patterson + Sheridan, and is head of the firm's trademark section, with deep expertise in consumer products, hand tools, and oilfield services.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Holland & Knight Hires Former Davis Wright Tremaine Managing Partner in Seattle

3 minute read

Newsmakers: Former Pioneer Natural Resources Counsel Joins Bracewell’s Dallas Office

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250