Changes to Patent Eligibility Under Section 101

Drawing on data aggregated from LexisNexis PatentAdvisor, the "abstract idea" exception in the 2014 case Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank has arguably been the most difficult to apply predictably or consistently.

February 28, 2020 at 10:27 AM

6 minute read

Joe Lally (left) and Temple Keller are intellectual property attorneys in the Austin office of Jackson Walker LLP. (Courtesy photos)

Joe Lally (left) and Temple Keller are intellectual property attorneys in the Austin office of Jackson Walker LLP. (Courtesy photos)

Most rejections issued by patent examiners at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office are based on the statutory provisions relating to novelty and nonobviousness: that is, whether an invention is new and sufficiently different from the "prior art" that existed beforehand. See 35 USC. §§ 102, 103. This article, however, discusses Section 101, which defines the patent-eligible categories of inventions.

Section 101 extends patent eligibility to "any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof." On its face, this provision would appear to impose few limits on what might be patented. With some notable exceptions, courts have historically been reluctant to create additional restrictions that go beyond the statutory language. For example, in Diamond v. Chakrabarty (1980), the Supreme Court found that "Congress intended statutory subject matter to 'include anything under the sun that is made by man.'"

Recently, however, patent eligibility under Section 101 has received significant attention. In a line of cases culminating in 2014 with Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank, the Supreme Court has held that laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are patent-ineligible concepts. In this article, drawing on data aggregated from LexisNexis PatentAdvisor, we focus on Alice's "abstract idea" exception, which has arguably been the most difficult to apply predictably or consistently.

In December 2014, the USPTO issued its Eligibility Guidance, attempting to craft an Alice-compliant framework for determining patent eligibility that can be applied uniformly by patent examiners. Patent applications are assigned to a particular USPTO art unit, or AU, based on their underlying subject matter, and the impact of Alice and the Eligibility Guidance has varied considerably among AUs. The AU Groups that examine inventions within the (somewhat controversial) business method field have seen the largest changes. See, e.g., The Impact of 101 on Patent Prosecution, Colleen V. Chien, (Oct. 21, 2018). In the view of its harshest critics, the Eligibility Guidance enabled examiners in the business method AUs essentially to forgo the traditional determination of an invention's novelty and non-obviousness, and instead issue rejections that relied on a cursory, scripted, and highly subjective determination about abstract ideas.

After five years of periodically updating the Eligibility Guidance in an attempt to incorporate and reconcile newly released judicial opinions, on Jan. 9, 2019, the USPTO issued the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance. The 2019 Guidance differed from all previous Eligibility Guidance by publicly acknowledging that:

Applying [Alice] in a consistent manner has proven to be difficult. … [I]t has become difficult … for … patent stakeholders to reliably and predictably determine what subject matter is patent-eligible. The legal uncertainty surrounding Section 101 poses unique challenges for the USPTO, which must ensure that its more than 8,500 patent examiners and administrative patent judges apply [Alice consistently and predictably] across applications, art units and technology fields.

Along with this admission, the 2019 Guidance articulated a qualitatively different eligibility determination by significantly limiting the number and scope of abstract idea categories that examiners could invoke.

Accordingly, although still purporting merely to summarize the existing case law, the 2019 Guidance resulted in an immediate decrease in Section 101 rejection rates (101 Rates). Figure 1 plots 101 Rates (defined as the percentage of examinations in which the examiner issued a Section 101 rejection) in the months immediately before and after the release of the 2019 Guidance. The impact of the 2019 Guidance is clearly observable in both the overall 101 Rate (which includes all types of Section 101 rejections), as well as the Alice-only 101 Rate (which is restricted to those rejections that are based on the Alice framework).

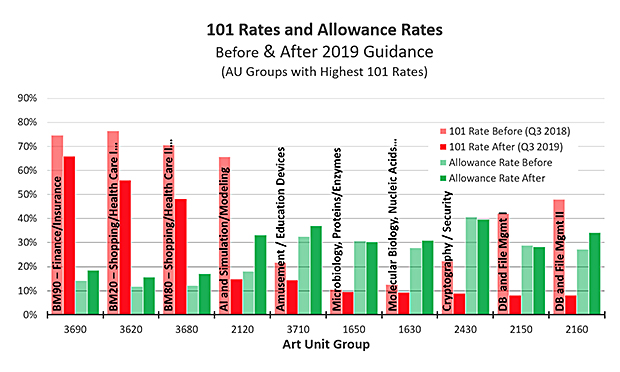

As noted above, 101 Rates vary widely among art units. Figure 2 illustrates these disparities in the effect of the 2019 Guidance on both the 101 Rate and the Allowance Rate (defined as the percentage of examinations in which the examiner issued a Notice of Allowance). Figure 2 provides data for the third calendar quarters immediately preceding and following the 2019 Guidance (Q3 2018 and Q3 2019) for the 10 AU Groups having the highest 101 Rates.

Only a few nonbusiness-method AU Groups had a large (20% or more) 101 Rate prior to the 2019 Guidance: Groups 2120, 3710, 2430, 2150, and 2160. Figure 2 suggests that the 2019 Guidance has substantially reduced the number of Section 101 rejections in those AU Groups. From the applicant's perspective, applications classified in these AU Groups may have been the biggest beneficiaries of the 2019 Guidance. In particular, AU Group 2120 (Artificial Intelligence) experienced a huge drop in 101 Rate accompanied by a roughly 15% increase in allowance rate.

The story is quite different in the business method AU Groups, however. Despite double-digit decreases in their respective 101 Rates, these Groups still have, by far, the highest 101 Rates. Interestingly, the large decreases in 101 Rates were accompanied by only modest increases in Allowance Rates, perhaps suggesting that most Section 101 rejections were not dispositive of the ultimate patentability determination.

The persistence of Section 101 rejections in the business method AU Groups might suggest that the USPTO continues to use eligibility to impose a heightened barrier to patentability for business method subject matter. Whether there should be a ban on business method patents, the Alice Court did not adopt such a bright-line rule (despite the suggestions of amici such as IBM). Until a business method exception is enacted judicially or legislatively, one could argue that the USPTO is operating beyond its administrative domain in this respect. Overall, however, patent applicants and patent prosecutors are likely to view the new statistics favorably.

Joe Lally and Temple Keller are intellectual property attorneys in the Austin office of Jackson Walker LLP. Both focus mainly on the field of patent prosecution.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

6 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

Special Counsel Jack Smith Prepares Final Report as Trump Opposes Its Release

4 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Corporate Litigator Joins BakerHostetler From Fish & Richardson

- 2E-Discovery Provider Casepoint Merges With Government Software Company OPEXUS

- 3How I Made Partner: 'Focus on Being the Best Advocate for Clients,' Says Lauren Reichardt of Cooley

- 4People in the News—Jan. 27, 2025—Barley Snyder

- 5UK Firm Womble Bond to Roll Out AI Tool Across Whole Firm

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250