How Did They Know? Exactly 1 Year Ago, This Legal Summit Taught Courts About Pandemic Preparations

"Now in 2020, we are all living it out," said Jeffrey Tsunekawa, director of research and court services in the Texas Office of Court Administration. "The timing was right on the money."

May 22, 2020 at 03:05 PM

4 minute read

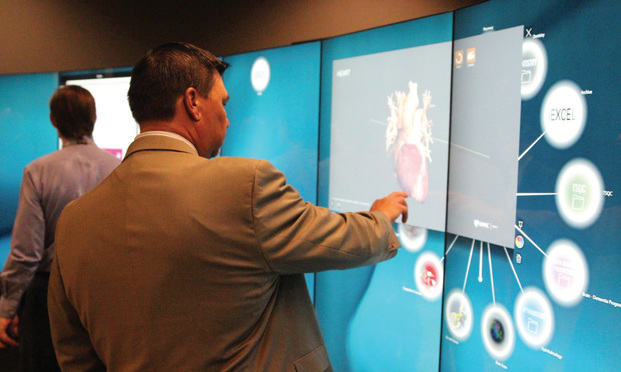

Nebraska State Court Administrator Corey Steel experiments with displays during the 2019 National Pandemic Summit. (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

Nebraska State Court Administrator Corey Steel experiments with displays during the 2019 National Pandemic Summit. (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

Touring one of the few hospital biocontainment units in the nation, Texas court administrator Jeffrey Tsunekawa was amazed.

He marveled at the protective gear, negative air pressure isolation rooms and meticulous sanitation procedures that doctors and nurses followed to stop cross-contamination.

Back then—May 2019—few had heard the word COVID-19.

Instead, everyone was talking about Ebola, Tsunekawa recalled about the judges and court administrators on the tour of the biocontainment unit at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. The tour was part of the 2019 National Summit on Pandemic Preparedness, an event aimed at educating courts about planning for a pandemic.

"It was good for a group from all over the country to come together and be faced with scenarios we never thought would happen, and now in 2020, we are all living it out," said Tsunekawa, director of research and court services in the Texas Office of Court Administration. "The timing was right on the money."

Back then, a pandemic was a theoretical threat. Nobody really thought it would happen.

Fast forward to the coronavirus pandemic, and the timing of the summit seems eerie, like the organizers had a crystal ball.

Photo: Mongkolchon Akesin/Shutterstock.com

Photo: Mongkolchon Akesin/Shutterstock.comJudges, court administrators and other government representatives from 35 states and U.S. territories attended the summit May 23-24, 2019, organized by the Nebraska Supreme Court and the National Center for State Courts. Attendees traveled from Texas, Florida, Georgia, New Jersey and a host of other locations.

They heard from doctors, judges, lawyers, and court administrators who talked about isolation and quarantine, how to draft a plan to continue operations and business during a pandemic, legal issues that could arise in states during a pandemic and more. Attendees separated into groups to complete tabletop exercises that made think through court operations in a pandemic.

Many of the attendees have said that the thing they took home from the summit that helped them the most when COVID-19 shuttered courthouse doors nationwide this spring, were those relationships they made with their states' other branches, public health authorities and judicial personnel across the nation, said Nora Sydow, principal court management consultant with the National Center for State Courts in Williamsburg, Virginia.

"Having those relationships in place let us hit the ground running," she recounted about the judicial staff feedback.

Sydow explained that the precursor to the event was fallout from the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa, in which American health care workers who responded were infected and brought home for treatment. The Omaha biocontainment unit treated some of them.

"All of a sudden, state court leaders—but also, trial court judges—were thinking our judges are totally unprepared for the unique legal questions that arise in a quarantine," Sydow said.

Rapid unfolding

Nebraska Supreme Court Chief Justice Michael Heavican, the one who organized the pandemic summit, said Nebraska was the perfect place because of the nearby biocontainment unit.

In Nebraska, Heavican said he's pleased that the judiciary released a bench book about the state's quarantine law. But if he could go back in time, he would have done more to make sure the courts really had a pandemic plan.

He explained, "It was difficult to get trial court judges to say anything more than, 'Yes, this is nice, but the likelihood we will every have to use it is so small.'"

Nebraska Supreme Court Chief Justice Mike Heavican welcomes attendees to the Summit on Pandemic Preparedness May 2019 at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

Nebraska Supreme Court Chief Justice Mike Heavican welcomes attendees to the Summit on Pandemic Preparedness May 2019 at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) (Photo: Courtesy Photo)The summit gave Heavican a general idea of what to expect in a pandemic. He expected that court staff would not be able to come to work, and knew that the courts would have to use technology to keep operating.

"We just didn't anticipate the kind of details we would need to think out," he added. "We didn't anticipate that it would happen so rapidly."

By being forced to embrace technology so fast because of the virus, Heavican said the courts will see a lasting impact.

"I don't think we would ever have done it, if it weren't for a pandemic," he said. "Hopefully, the legal profession and the various state court systems and federal court system will come out of this better—better able to serve people."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

6 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Loopholes, DNA Collection and Tech: Does Your Consent as a User of a Genealogy Website Override Another Person’s Fourth Amendment Right?

- 2Free Microsoft Browser Extension Is Costing Content Creators, Class Action Claims

- 3Reshaping IP Policy Under the Second Trump Administration

- 4Lawyers' Reenactment Footage Leads to $1.5M Settlement

- 5People in the News—Feb. 4, 2025—McGuireWoods, Barley Snyder

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250