Texas Prison Exec Says Risk Assessment Could Score Women As Higher Risk Than They Actually Are

Researchers say that scoring men and women differently is essential to account for risk assessment tools' inherent gender bias. But it's an open question whether these adjustments are violating state or constitutional law.

July 20, 2020 at 10:00 AM

5 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Legal Tech News

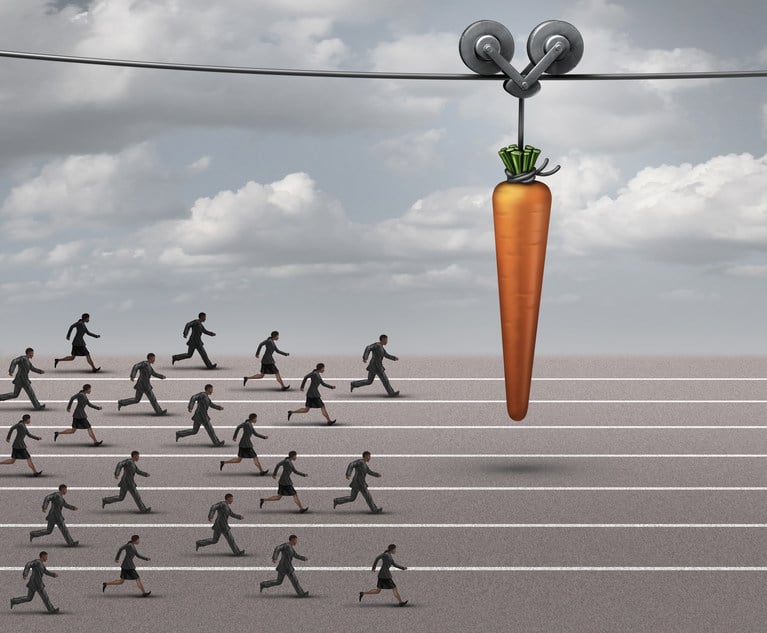

While there's been a lot of focus on how risk assessment tools treat different racial demographics, little attention has been paid to another issue that may be just as problematic: how gender factors into risk scores. Researchers say accounting for the differences in gender ensures that risk assessments are more accurate, but exactly how they do so may run into constitutional challenges.

Legaltech News found one gender-specific risk assessment tool currently implemented in at least two states: the Women's Risk and Needs Assessment (WRNA), which like the the Ohio Risk Assessment System (ORAS), was created by the University of Cincinnati. Kansas uses the WRNA to assess parolees' risk in a women's prison in Topeka, while Montana deploys it for women on probation or parole throughout its Department of Corrections.

Amy Barton, a spokesperson for Montana Department of Corrections, explains that while the WRNA uses gender-neutral risk factors, it also looks at more "gender-responsive factors," including "relationship support and conflict, parental involvement and stress, self-efficacy, prior physical and sexual trauma, housing safety, mental health and anger/hostility."

The reason WRNA is needed in the first place is because most risk assessment instruments are validated (i.e. created) on a population that is majority male, in large part due to current gender imbalance in the criminal justice system (i.e. more men than women commit crimes and become incarcerated).

Dr. Teresa May, department director of the Community Supervision & Corrections Department in Harris County, Texas, also notes that on a whole, men have higher recidivism risk than women. "What we know is when you look at gender, almost always—and in fact I don't know of an exception—the average rearrest rate [for women] is always much lower than men."

Without accounting for these differences, a risk assessment could end up scoring women as higher risk than they actually are.

To be sure, there are other ways to account for gender differences in risk scores without using a gender-specific tool. Some tools, for example, such as Oregon's Public Safety Checklist (PSC) and Pennsylvania's Sentence Risk Assessment Instrument, use gender as a risk factor, essentially assigning men higher potential risk scores than women.

Jurisdictions can also have separate risk level cutoff scores for men and women. May notes with that when Texas implemented the Ohio Risk Assessment System (ORAS) in its criminal justice system, it "used separate cut points to make sure women are not being overclassified—that is, [assigned] higher risk than they really were."

Legal Battles

There's an ongoing debate over whether using gender as a risk factor, or assigning different cutoff risk levels to both males and females, violates the 14th Amendment. "Basically the Supreme Court of the U.S. has pursued what's called an anti-classification approach to the equal protection law, which prohibits explicit use of factors like gender and race in making decisions," says Christopher Slobogin, professor of law at the Vanderbilt University Law School.

He adds, "It is permissible, constitutionally, to use race or gender if there is a compelling state interest in doing so. But generally speaking, the use of race and gender is unconstitutional to discriminate between groups."

However, in Slobogin's own opinion, he does not think the "Constitution is violated simply because a risk assessment arrives at different results for similarly situated men and women." He argues that a tool that uses gender as a risk factor and one that has different cutoff scores for genders are functionally the same, adding in those adjustments makes the instruments more accurate.

But others see it differently. Sonja Starr, professor of law at the University of Michigan Law School, for example, recently told the Philadelphia Inquirer that "use of gender as a risk factor plainly violates the Constitution."

Still, constitutional challenges against risk assessment tools in court have yet to materialize. But Slobogin, noting the amount of risk assessment tools used in sentencing, believes it's only a matter of time. "I think right now, there are some cases brewing."

There has been at least one case on the state level that addressed the legality of using gender in risk assessment. In Wisconsin v. Loomis, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that the use of gender by Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) tool does not violate a defendant's due process right. Specifically, the court noted, "The inclusion of gender promotes accuracy, it serves the interests of institutions and defendants, rather than a discriminatory purpose."

Whether the use of gender in risk assessment tools violate other states' laws is still to be determined. Slobogin notes that states like Arkansas, Florida, Ohio and Tennessee "have statutes that prohibit sentencing on gender," among other factors.

However, "on the other hand, these statues often say something like, the state must be neutral in using gender… and I could read that to mean so long as the instruments are accurate with respect to how women or men are treated, then that's a neutral treatment," he adds.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms Are 'Struggling' With Partner Pay Segmentation, as Top Rainmakers Bring In More Revenue

5 minute read

Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1New Strategies For Estate, Legacy Planning

- 2Leaning Into ‘Core’ Strengths, Jenner’s Revenue Climbs 17%, Profits Soar 23%

- 3Frito Lays Could Face Liability for Customer's Grocery Store Fall Over Pallet Guard, Judge Rules

- 4Holland & Knight Expands Corporate Practice in Texas With Former Greenberg Traurig Partner

- 5Heir Cut: Florida Appellate Court Backs Garth Reeves' Will

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250