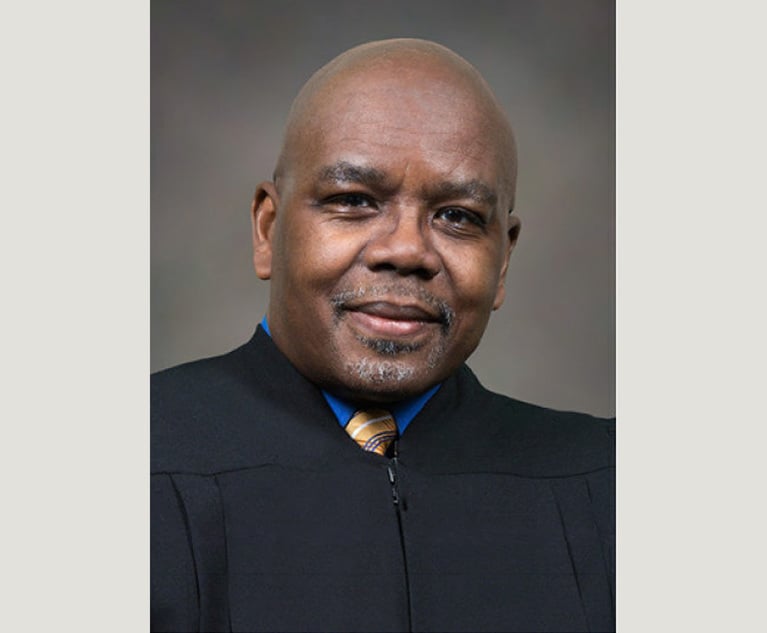

David Evenhuis of McNees Wallace and Nurick.

David Evenhuis of McNees Wallace and Nurick.Generating Value From Public Assets Through Community Needs

Monetization is the process of converting an asset into economic value. For municipalities and public sector entities, the process has historically involved the ownership and operation of public utilities like water and sewer systems. But the delivery of utility services is becoming increasingly complex and subject to greater regulation each year. And many public sector operators have experienced a decline in financial returns.

October 05, 2017 at 01:32 PM

6 minute read

Monetization is the process of converting an asset into economic value. For municipalities and public sector entities, the process has historically involved the ownership and operation of public utilities like water and sewer systems. But the delivery of utility services is becoming increasingly complex and subject to greater regulation each year. And many public sector operators have experienced a decline in financial returns.

Looking for options to generate more revenue, many municipalities have considered the transfer of such assets to private operators, or the creation of public-private partnerships. Public sector entities have also been harnessing new technologies and ideas to transform underutilized or dormant assets into economic value.

There can be great financial opportunity in monetization, but municipalities should be aware of the common dangers and oversights. And in all cases, the potential for successful economic returns must be informed by the values and needs of the community.

|Disposition of Utility Assets

In a disposition of public utility assets, monetization tends to be a conversion rather than a creation of value. With assets such as water and sewer systems being “monetized” to the extent that they already produce a financial return, a sale or lease to a private operator does not create entirely new value. It changes the revenue model—hopefully with a better return for the public entity.

An outright sale will convert steady annuity-type returns into immediate liquidity. Under the terms of a typical agreement, title will be conveyed to all above-ground and underground facilities (treatment plants, water towers, pumping stations, pipes, valves and access points), together with the underlying real estate interests (fee title, easements). Payment tends to be in the form of a one-time lump sum.

A disposition of utilities may also take the form of a long-term lease, known as a “concession” agreement. Under a concession with a private operator, the public sector owner may have more opportunity to negotiate a balanced financial return that combines a significant up-front payment with a tail from operational revenues.

The interests and financial needs of the community will likely determine whether a sale or lease is more desirable. Too often, however, public sector entities jump into deals without understanding the potential liabilities that may result. It's therefore extremely important to engage experienced counsel early in negotiations to advise about the process and undertake thorough due diligence to help ensure a smooth transition.

|Due Diligence in Dispositions

The importance of good due diligence can't be overstated when preparing for a disposition of public utility assets. A municipal entity can face significant liability for attempting to convey more than it actually owns. Such was the case for the Scranton Sewer Authority, which last year finalized a $195 million sale of its sewer system to a private operator.

After the parties entered into a purchase contract, it was discovered that for decades the Authority had been using sewer lines under nearly 600 properties for which it had no clear easements. To make matters worse, the Authority attempted to resolve the issue by sending a letter to affected property owners insisting that they accept $100 in exchange for granting an easement within seven days, or face condemnation.

Just as the deal was closing, several homeowners were so irritated by the authority's actions that they filed a class-action suit seeking millions in damages. The authority itself had already paid significant legal fees to complete the transaction, and it had to set aside millions more to attempt to resolve the litigation. With thorough and early due diligence, this may have been avoided.

|Developing Land Assets

One of the more underutilized municipal assets is land. The financial upside for land development is potentially great, as it may be an opportunity to unlock value from a zero-revenue asset. After mapping available properties, a municipality can explore the question of what can be monetized.

Consulting companies may be helpful in determining projects appropriate for different tracts of land. Real estate developers may also be interested in contributing to the conversation, as it may give them entry to developed locations attractive to outside businesses. But ultimately the municipality should seek to drive business and raise revenues for itself in the bargain.

Public lands may also be developed for energy projects, which are particularly attractive for public-private partnerships. Whether partnering for oil and gas exploration or the development of a solar farm, such partnerships can be a boon for municipalities, with capital funding coming from the private sector.

By partnering with energy providers, municipalities have also been able to unlock the value of formerly “passive” assets like undeveloped tracts and unused rights of way. In today's model for solar development, the municipality provides the land, and the producer generally covers all costs of the facilities. Clean power is then sold to the municipality, often at a savings from traditional sources.

Under permissible arrangements for net-metering, public sector entities may be able to generate additional revenue by selling surplus power to the energy grid. A successful example is a power-purchase agreement between the Oregon Department of Transportation and Portland General Electric, where the parties transformed previously unused rights of way into “solar highways,” generating cost savings for the state and feeding power into the grid.

|Donated or Dedicated Property

Unfortunately not all land may be monetized. Before engaging in any project to develop, dispose or change the use of public land, a municipality must first determine whether it had been donated or dedicated for a particular use. Under Pennsylvania's Donated or Dedicated Property Act, all real property donated or dedicated to a political subdivision for public use is considered to be held in trust for the benefit of the public.

Municipalities may not sell such property or change its intended use without first obtaining permission from the orphans' court, which has exclusive jurisdiction under the act. For a sale to be approved, the original purposes of the dedication must no longer be practical and the property shall have ceased to serve the public interest. Examples of improper dispositions include the sale of public parkland to a private golf course developer and the lease of a small portion of dedicated parkland for a communications tower.

While courts have held that leases of municipal land must also be approved by the orphans' court, the act does not cover lands held by authorities or other nonmunicipal entities. Moreover, the act does not affect a municipality's right to dispose or change the use of lands or buildings acquired by purchase or condemnation. When seeking opportunities for monetization, these land assets should be considered first.

David Evenhuis is a real estate attorney at McNees Wallace & Nurick in Harrisburg. He focuses on commercial purchases and sales, realty transfers within mergers and acquisitions, and dispositions of public assets. He can be reached at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Plaintiffs Seek Redo of First Trial Over Medical Device Plant's Emissions

4 minute read

Disjunctive 'Severe or Pervasive' Standard Applies to Discrimination Claims Against University, Judge Rules

5 minute read

High Court Revives Kleinbard's Bid to Collect $70K in Legal Fees From Lancaster DA

4 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250