Lawsuits Shine Spotlight on Law Firm Advertising Practices

A recent federal court decision sent a message to law firms: Lying in advertisements about your firm may be wrong, but it won't necessarily carry a price tag in civil litigation.

March 05, 2018 at 06:30 PM

6 minute read

A recent federal court decision sent a message to law firms: Lying in advertisements about your firm may be wrong, but it won't necessarily carry a price tag in civil litigation.

That was one of the takeaways from a Feb. 15 ruling by U.S. District Judge Cynthia M. Rufe of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, who refused to condone the advertising practices of Philadelphia plaintiffs firm Lundy Law, but granted summary judgment in favor of the Lundy firm nonetheless.

Another Philadelphia firm, Larry Pitt & Associates, had sued Lundy Law, alleging, among other things, that Lundy advertised legal services it does not actually provide. Rufe agreed on that count, finding that wrongdoing by the defendant firm was clear. But that didn't mean Lundy Law could be held liable, she concluded.

“There is every indication here that a prominent personal injury law firm in Philadelphia essentially rented out its name in exchange for referral fees and that its managing partner lied on television that his firm handled Social Security disability claims when it did not,” Rufe wrote. “But when a plaintiff fails to meet its burden of establishing causation of harm or likelihood of future violations, the Lanham Act and Pennsylvania law do not permit a court to grant relief based solely on a defendant's past misrepresentations.”

The Pitt firm's lawyer, Maurice Mitts of Mitts Law, said he wasn't ready to say whether his client would appeal. Either way, he will get a chance to test the law again in a similar case that's been pending since last fall.

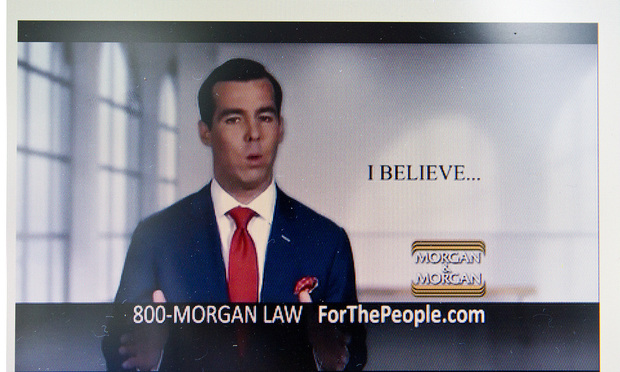

Mitts is representing Philadelphia-based Rosenbaum & Associates, which sued national plaintiffs firm Morgan & Morgan in September 2017. Like Pitt, Rosenbaum brought false advertising claims under the Lanham Act. The Rosenbaum firm alleged that Orlando-based Morgan & Morgan falsely advertises that it represents clients in Philadelphia, when it only has one lawyer in Pennsylvania with “little or no experience in handling personal injury matters.”

Rosenbaum has claimed that Morgan & Morgan's advertising in Philadelphia has caused a decline in the number of new clients coming to Rosenbaum & Associates.

Mitts said the Pitt firm's case gave the issue new visibility. And while he said the legal strategy in each case is different, he said they share a common theme.

“They're both about a baseline of integrity in lawyer advertising, and that [deception] ought not to be tolerated,” Mitts said.

Other area lawyers said the two cases, while similar, don't suggest that more and more law firms are taking each other to court over ads. As national personal injury practices grow, they said, litigation is not necessarily the most effective way to deal with deceptive advertising claims.

Guarding Their Turf

“What's happened in Philly is not unusual,” said Bruce Carlson, co-founder of Carlson Lynch Sweet Kilpela & Carpenter in Pittsburgh. “It's very common for those local lawyers to become territorial” when out-of-town firms allegedly stretch the truth in their ads.

Carlson, whose firm has a national class action practice, said Carlson Lynch seeks pre-approval from local ethics officials before running advertising in other markets.

“We have had lawyers in other parts of the country file disciplinary complaints against us—ill-founded, but it's not uncommon to occur,” Carlson said.

Generally, lawyers are truthful in their advertising, said Abraham Reich of Fox Rothschild, who teaches legal ethics at University of Pennsylvania Law School. Still, he said, while declining to comment on the specifics of the Lundy or Morgan & Morgan cases, it's not impossible to prove that a law firm has lied in its ads.

“When you cut through the analysis and the hundreds of pages of Supreme Court [opinions] and other case law, the bottom line is that advertising has to be truthful,” he said.

The consequences depend on the severity of the allegedly false advertising, Reich said, and those consequences could come in many forms.

“If you advertise something that is not truthful, you expose yourself to some repercussions, whether they exist at a disciplinary board level, or a competitor [sues], or a court decides to sua sponte raise the issue,” he said.

The American Bar Association's model rule on lawyer advertising states that an attorney “shall not make a false or misleading communication about the lawyer or the lawyer's services. A communication is false or misleading if it contains a material misrepresentation of fact or law, or omits a fact necessary to make the statement considered as a whole not materially misleading.”

But each state has its own limits on and requirements of lawyer advertising. For instance, Pennsylvania is one of eight states that requires the ad to disclose the practice location.

That's why Carlson Lynch, as a best practice, makes sure ads pass the local ethics requirements before running them, Carlson said. That won't keep local law firms from becoming upset, he said, but it will prevent bigger problems arising from that.

“There are an increasing number of large firms that have a national footprint,” Carlson said. “As those firms try to expand their reach and cut into the potential business of local firms, it would not be unusual to … get some sort of reaction from local firms.”

Still he said, ethics complaints are a more common reaction than litigation. And he added that “most firms that operate at that [national] level have a pretty sophisticated approach to ethics compliance.”

Back in Court

Not long after the Pitt case was dismissed, Rosenbaum & Associates filed a new complaint against Morgan & Morgan. It makes the same claims, but adds a number of details found in discovery, including specific statements in Morgan & Morgan commercials.

“We were anticipating this approach and we will respond in court,” Morgan & Morgan's lawyer, Gaetan Alfano of Pietragallo Gordon Alfano Bosick & Raspanti, said in a statement.

Mitts, who entered his appearance in Rosenbaum's case in January, said his approach to the cases was already different before Rufe made her ruling. And Rosenbaum's case is on a faster track, he said, with trial tentatively scheduled for June.

Despite his summary judgment loss in the Pitt case, Mitts said it was significant that Rufe suggested in her ruling that Lundy Law should face disciplinary consequences.

“It is important that you have a federal judge who is announcing that this is willfully dishonest,” he said. “That recognition is a driver in both cases.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'The World Didn't End This Morning': Phila. Firm Leaders Respond to Election Results

4 minute read

Settlement With Kleinbard in Diversity Contracting Tiff Allows Pa. Lawyer to Avoid Sanctions

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250