Playing Both Sides: Facing the Harsh Truth of Law Firm Service Duality

Recently, Hugh A. Simons wrote for American Lawyer an enticing argument advocating elite law firms increase their rates. In one striking comment, Simons suggests elite law firms jettison any and all commodity services.

March 27, 2018 at 04:00 PM

9 minute read

Smart Strategy

Recently, Hugh A. Simons wrote for American Lawyer an enticing argument advocating elite law firms increase their rates. In one striking comment, Simons suggests elite law firms jettison any and all commodity services. In justifying his position he states “… managing businesses with dramatically different fund strategies requires ambidexterity few trained business leaders, let alone lawyers, possess.” While catering to high-end needs may certainly simplify operational management, the practicality of this approach is limited to no more than a handful of truly elite firms—leaving the vast majority of firms—including some of today's highest performers— demanding a different modus operandi.

The market for legal services today is not the same as it was in 2007 (the year from which Simons conducts his rate analysis.) Increased price transparency, more sophisticated in-house counsel and technological advances have dramatically—and permanently—shifted the way in which buyers acquire legal services. Whereas in the past clients took the lead from law firms in defining high-end practices worthy of premium rates, today's clients have the tools and information to make smarter, wiser purchase decisions. Does this insight more greatly impact the lower-end of the services spectrum? Perhaps. Yet it also changes the dispersion of legal services. Consider the below graphic illustrating the evolution of the legal services spectrum.

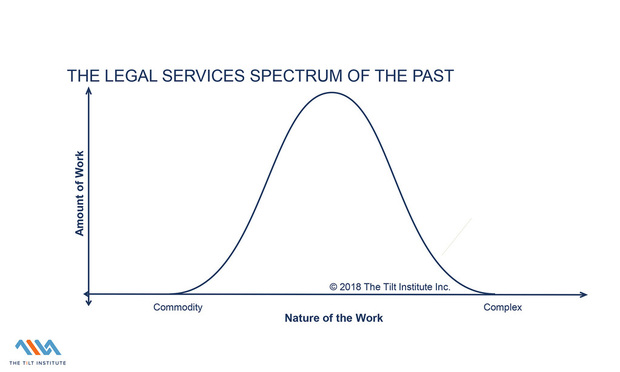

Figure 1 depicts a pre-transparency era vision of legal services (surprisingly not that far into the past) during which clients instinctively knew what was bet-the-company or nuisance yet the bulk of work was somewhat amorphous and, by default, landed somewhere in the middle.

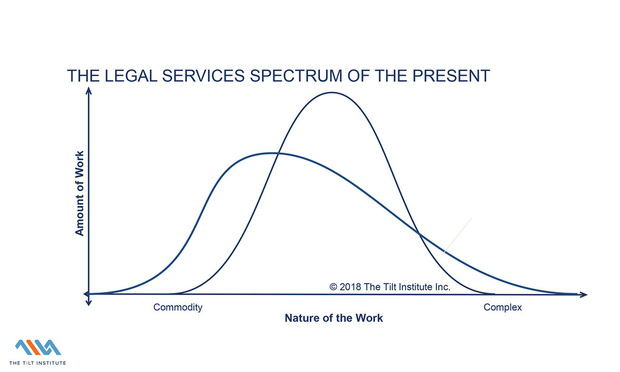

Figure 2 illustrates recent shifts where increased access to data, analytics and matter management tools has flattened out the legal services spectrum, shifting more matters to the commodity-end of the spectrum. Increased certainty and transparency has aided clients in better determining the value of a particular matter and widespread adoption of early case assessment and similar tools has helped clients to downgrade work.

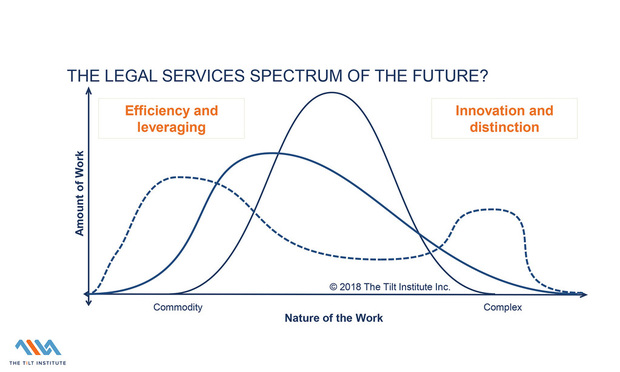

Figure 3 posits a vision for the future based on current trends including advances in data sharing and collaboration among clients, the rise of professionals dedicated to legal operations and, with a nod to Simons, the increasingly complex, interwoven nature of business needs and risks. This predicted outcome yields a model in which law firms see an uptick of available work at both the higher and lower ends of the spectrum, with a dip in the middle-tier work.

The challenge for the vast majority of law firms will be not to ditch their lower-producing brethren but to reengineer them to function profitably. Clifford Chance, who recently acquired the managed services arm of Carrillions, or Dentons who launched NextLaw Labs in 2015 are examples of top-tier firms proactively investing in a future with—not exclusive of—this dichotomy of offerings. Industry dynamics are transforming not just the practice of law but also the way it is delivered, bought and sold. In the words of one client discussing his perspective on acquiring legal services (and relatedly the viability of ASPs), “My job is to reduce risk to the company and lower the cost of legal services. If I did not look at all the options I would not be doing my job.”

Why Not Ditch?

The cases for keeping commodity practices are seemingly endless, so we will focus on four:

- The lifecycle of legal services

- Services in relation to cycles

- Consistent revenue streams

- The profit opportunity

The Lifecycle of Legal Services

Legal service offerings evolve from nascence to maturity similarly to the cresting of a wave. Optimizing access to price premiums demands entering the wave before it peaks and riding it as long as possible. Legal expert Patrick McKenna describes this phenomenon well in his piece “Developing Your Growth Strategy: Seeking Clear Blue Water.” Law firms who wish to access premium rate areas in the future must be willing to experiment and invest in areas that may not command premium rates today. An elite law firm shunning investment in these new growth areas due to their initially lower rates or profit margins most likely will, over time, find itself at the tail end of the wave.

Services in Relation to Economic, Political and Regulatory Cycles

The boom and bust of economic cycles similarly wreaks havoc on the concept of spinning off seemingly commoditized work. As the economy shifts downward, law firms can expect to see an uptick in bankruptcy, certain types of litigation and targeted transactions by financially strong (and savvy) clients. Other areas, including some distinctive practices such as antitrust or FDA, ebb and flow with the political tide. The investment equivalent to Simons' recommended approach would be to build a portfolio entirely of equities without any positions in bonds, for example. It works great for a while, but when the market crashes the impact hits hard with no cushion on which to land. Only a firm financially strong enough to ride the ups and downs of these cycles will survive with limited areas to serve to mitigate risks.

Consistent Revenue Stream

Audit services are not the most profitable service lines at the Big Four and yet they all offer them. Why? Ongoing, predictable revenue streams are highly coveted, as are inroads to large, attractive client relationships with the potential to spin-off other, more lucrative work (e.g, tax advisory) and the opportunity to train and groom young accountants. Adam Severson, chief business development officer at Baker Donelson refers to the legal equivalent of audits as “run-the-company” work. It may lack the glamour and top-notch rates of “bet-the-company” matters, yet this lower rate work in essential business areas such as employment, intellectual property, contracts, financing and real estate can be what keeps the lights on. And another boon in the face of cyclical legal needs. Furthermore, a consistent flow of often highly leverageable work creates the ideal environment for developing talent. With the rate of lateral success bordering a coin toss, this next generation of talent is increasingly vital to the future of virtually every law firm.

Jones Day is a master at delivering routine work to clients, and not at the expense of an increasingly prominent global reputation. The third fastest growing law firm from 2009 to 2016 according to Nicholas Bruch's analysis of the AmLaw 200, Jones Day regularly services the ongoing needs of Fortune 1000 clients. Jones Day routinely delivers multiple services to their largest clients. At the same time, Jones Day's brand surpassed all others in Acritas' US Law Firm Brand Index 2018, after overtaking former leader Skadden in 2017.

The Profit Opportunity

Finally, there is the opportunity to make money—lots of it. As the alternative service providers are well aware, commodity legal services can deliver exceptional margins if delivered efficiently and effectively. What challenges most law firms today is not the low rates themselves but rather the way in which they are managing, delivering and pricing them. For example, law firms proactively using alternative fee arrangements (an effective pricing tool for commoditized services) are generating as much, if not more, profits on their services priced under alternative fee arrangements as those delivered under the traditional billable hour. Increased adoption of the three P's (pricing, project management and process improvement), technology integration and the use of alternative staffing models—including outsourcing—will continue to improve this figure. Entire firms, including Fragomen and Barlit Beck, have benefited considerably from optimizing a nontraditional approach to delivering legal services (Fragomen delivers exclusively immigration services, a so-called commodity, under a highly leveraged model with a notably small partner class; Barlit Beck, founded in 1995 with a 100-percent alternative fee approach, offers an array of high and low-end litigation.) The profit opportunity for other large firms is one not to be ignored.

One last point to respond directly to the idea that few firms will be able to manage the delivery of legal services at both ends of the spectrum: most already are. Sure, some are doing it more successfully than others but the idea of having practice areas—or individuals for that matter— with different contribution levels is not new to law firms. In fact, it is not unique at all. IBM manages business segments with gross margins ranging from 25.2 percent (Global Financing) to 78.6 percent (cognitive solutions) according to its most recent filing.

What is new to law firms is a world in which managing this disparity will grow increasingly challenging and complex as the spectrum from the high-end to the low-end widens. The critical success factors to compete for premium work will differ from the more routine. The law firm partner model, already under scrutiny in the wake of Trump's tax reform, will require examination. Likewise, the compensation structures, performance metrics and role of business professionals will need to evolve. As Mark Smolik, general counsel of DHL so succinctly put during the Business of Law Forum in New York City in January, “Yes, you're going to have to blow up the system. It's not working folks.” So before you raise your rates and jettison those “commodity” practices, be certain to take a good, hard look at what the data, trends and clients—yes, clients—have to say about it.

Marcie Borgal Shunk is president and founder of The Tilt Institute, a firm dedicated to unveiling new perspectives on law firm growth through intelligence, innovation and intuition. She specializes in helping law firm leaders make better, data-driven business decisions.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pa. Federal District Courts Reach Full Complement Following Latest Confirmation

The Defense Bar Is Feeling the Strain: Busy Med Mal Trial Schedules Might Be Phila.'s 'New Normal'

7 minute read

Federal Judge Allows Elderly Woman's Consumer Protection Suit to Proceed Against Citizens Bank

5 minute read

Judge Leaves Statute of Limitations Question in Injury Crash Suit for a Jury

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Navigating AI Risks: Best Practices for Compliance and Security

- 220 New Judges? Connecticut Could Get Wave of Jurists

- 3Orrick Loses 10-Lawyer Team to Herbert Smith in Germany

- 4‘The US Market Is Critical’: KPMG’s Former Head of Global Legal Services On the Legal Arm of the Big Four Firm Entering the US

- 5Justice Marguerite Grays Elevated to Co-Chair Panel That Advises on Commercial Division

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250