EB-1 Immigrant Visa Program: Apparently, It's Not Just for Einsteins

We are only a few months into the Trump presidency's second year, and immigration remains at the forefront of policy and public debate.

April 18, 2018 at 03:17 PM

5 minute read

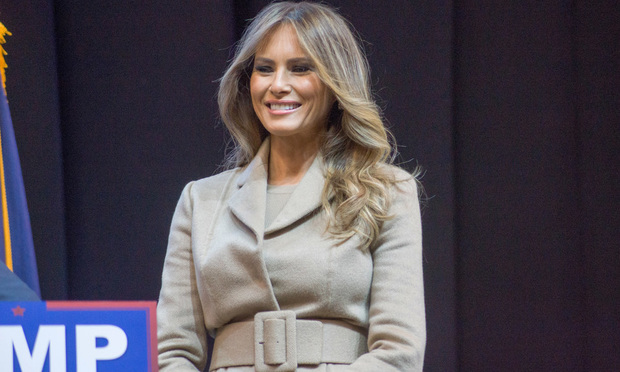

We are only a few months into the Trump presidency's second year, and immigration remains at the forefront of policy and public debate. Recently, however, scrutiny was turned on the First Family itself, with a March 1 article in the Washington Post calling into question First Lady Melania Trump's qualifications for the permanent residency granted to her in 2001 under the EB-1 immigrant visa program. The piece quoted legislators and lawyers who described EB-1 as “the Einstein visa,” reserved only for the likes of renowned academic researchers, Olympic athletes and Oscar-winning actors. The article brought this elite means of employment-based immigration into the spotlight, igniting discussion across the news media.

This characterization of the EB-1 program, however, paints an unduly restrictive picture of its scope and bar for entry. Yes, a successful EB-1 applicant must show that they have established themselves among the top professionals in their field—but they need not be a household name nor a “capital-G” genius.

In fact, hypothetically speaking, had Albert Einstein attempted to immigrate under the EB-1 program even a full decade into his career, his success would not have been certain. A March 4 followup to the Post article published by the New York Times provided an entertaining illustration of this, recounting an exercise in which a blind assessment of Einstein's 1920 résumé by a group of immigration attorneys yielded a general agreement that the subject individual was a bit underqualified and would make for a rather challenging petition.

Consider that 1920 was just one year before Einstein was granted the Nobel Prize in Physics. This goes to show that there is no clear-cut set of qualifications that make someone an ideal EB-1 candidate. The narrow interpretation of EB-1 requirements promoted in the Post article not only ignores the regulatory realities of the program, it portrays this visa classification not as exclusive, but exclusionary.

It is the ambiguity and subjectivity of the petition adjudication process, in fact, that opens the door for a broad and varied pool of applicants. Each EB-1 petition is first evaluated on the basis of whether or not the applicant meets a minimum number of regulatory criteria deemed to be markers of having sustained national or international acclaim. This is the easy part. The majority of the regulatory criteria can be addressed by providing objective documentary evidence. To show that the applicant is a published author on subjects in their field, for example, you submit copies of their published works. To show that they have commanded a high salary, you submit pay stubs with comparisons to mean wages for their occupation. Pretty cut and dried.

The process becomes murkier when, upon having determined that the applicant meets the requisite criteria, the adjudicator then subjects the petition to an overall merits analysis. This is where the adjudicator takes the sum of the evidence, both documentary and testimonial, and makes a determination about the significance of it all. They ask whether or not it is clear that the applicant possesses the high level of expertise required for EB-1 extraordinary ability classification. It is a lofty, ill-defined, but nevertheless imposed standard. And furthermore, apex expertise looks different in every field.

That is why, above all, a strong EB-1 petition needs to tell a story. It cannot be expected that the USCIS adjudicator will know anything at all about the applicant's field, so providing context is vital. The petition needs to establish the markers of accomplishment in the applicant's field of expertise, show that the applicant's career is characterized by said markers, and delineate the ways in which the applicant has distinguished themselves from peers in the field by achieving above and beyond them.

This is where the open-ended, narrative aspect of EB-1 petition presentation comes in, and where the recent furor over the First Lady's extraordinary ability classification is misplaced. Beyond the plain language of the regulatory criteria, a successful EB-1 applicant need not fit some rigid mold. In fact, the classification's clause allowing for submission of comparable evidence in the instance that the regulatory criteria do not apply to the applicant's occupation entirely does away with even the semblance of a mold to be broken.

What is required is the painting of a persuasive and logical picture of the applicant's recognized abilities and standing in their profession through a symbiotic presentation of documentary and testimonial evidence. With the right approach, there is room under the tent for cancer researchers, brain surgeons, photographers, dog breeders, models, you name it. If there is a job to be done, and there is someone who does it extraordinarily well, there is a path to EB-1. It just might require a little trailblazing.

The whole point of the EB-1 program is to bring the brightest and the best to the United States. But it is clear to anyone who looks that genius is not sequestered in the ivory tower of academia. Attracting and retaining the world's top talent should be a priority regardless of profession. You don't have to be Einstein to know that.

Feige M. Grundman is an attorney for Klasko Immigration Law Partners' Philadelphia office. She has experience in preparing tailor-made petitions based on a person's contributions, including EB-1, O-1, and National Interest Waiver petitions. She can be reached at [email protected].

Steven R. Miller is the editor in the firm's Philadelphia office. Miller works with a team of writers and attorneys to prepare EB-1, O-1, and National Interest Waiver petitions for clients who have extraordinary ability in the sciences, business, or the arts. He can be reached at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

AI and Social Media Fakes: Are You Protecting Your Brand?

Neighboring States Have Either Passed or Proposed Climate Superfund Laws—Is Pennsylvania Next?

7 minute readTrending Stories

- 1States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 2Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 3Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 4Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 5Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.