Meek Mill Is Free, but Faces Winding Road Before End of Legal Troubles

For court watchers and fans of hip-hop star Meek Mill, the past few weeks have been a rocky ride. But just because the state Supreme Court granted the embattled rapper rare King's Bench relief does not mean the star's legal woes are over.

April 26, 2018 at 12:09 PM

6 minute read

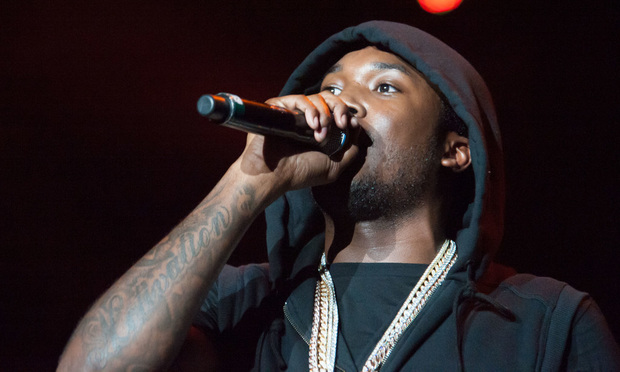

Meek Mill. Photo: Randy Miramontez/Shutterstock.com

Meek Mill. Photo: Randy Miramontez/Shutterstock.com For court watchers and fans of hip-hop star Meek Mill, the past few weeks have been a rocky ride. But just because the Pennsylvania Supreme Court granted the embattled rapper rare King's Bench relief—springing him from jail just in time to ring the bell at the Philadelphia 76ers playoff game—does not mean the star's legal woes are over.

According to court watchers, the Philadelphia judge handling Mill's appeal still has a lot of leeway, which could tie the case up with further appeals and further complicate what attorneys already say is a very complicated situation.

Mill's case traces back to his 2008 conviction on drug- and gun-related charges for which he was sentenced to probation. After violating probation twice in 2017, Philadelphia Judge Genece Brinkley slammed Mill, whose real name is Robert Williams, with a two- to four-year sentence, stunning both Williams' fan base and criminal justice attorneys alike, since neither Williams' probation officer nor the prosecutor on the case had sought jail time.

A very public feud emerged between Williams and Brinkley, but, most significantly in terms of Williams' appeal, so did reports of a list of Philadelphia police officers who have severe enough credibility problems that the district attorney's office does not put them on the stand. That list, according to multiple media reports, included Police Officer Reginald Graham, who was a key witness during Williams' 2008 trial.

In February, Williams filed an appeal under the Post-Conviction Relief Act, focusing on Graham's credibility issues. In an unusual move, prosecutors agreed that Williams should be released on bail and that he should get a new trial.

Although Brinkley denied Williams' renewed bail request following his latest appeal and scheduled a hearing to delve into the PCRA arguments for June, the Supreme Court on Tuesday ordered that Williams be released on unsecured bail and told Brinkley to expedite Williams' PCRA appeal. The order came following a rarely granted direct appeal to the justices, known as a King's Bench petition.

According to criminal defense attorney Steven Fairlie of Fairlie & Lippy, although it is extremely rare for a judge to deny a petition when both sides agree it should be granted, Brinkley still has the power to deny Williams' PCRA petition since there already was a conviction in the case.

“The PCRA petition is up to her,” Fairlie said.

Defense attorney Matthew Mangino, formerly the Lawrence County district attorney, agreed that judges have discretion to reject PCRA petitions, although he also acknowledged it is very rare.

“The judge could still say, 'I think this witness is credible.' Him lying in one case does not mean he's lying in all cases,” Mangino said. “That would be an unusual position for a judge to take. But it was an unusual situation with regard to bail.”

However, he said that, if both sides stipulate to the same set of facts on the appeal, the judge has little wiggle room.

“We work within an adversarial system,” Mangino said. “If both sides agree … that adversarial situation disappears, so I'm not sure how the court makes a decision that's different than what the parties have agreed to.”

Mangino noted that the prosecutor's posture in the case is largely what has narrowed Brinkley's discretion in the case. When it was simply a probation-related proceeding, Brinkley had very wide discretion, making it very unlikely any higher court would find her initial two- to four-year sentence to be an abuse of that discretion.

However, with the prosecutors agreeing Williams should get a new trial, at least, Brinkley's discretion has shrunk significantly.

“If the underlying conviction is tossed, your supervision is no longer a factor,” Mangino said. “You're looking at something entirely different than when you began.”

If Brinkley decides to deny the PCRA petition, the case will once again have to climb the appellate ladder, which can often take a year or more.

Along with how Brinkley will handle the PCRA, two significant questions remain unanswered. The first is how the prosecutor's office will treat a new trial, and the second is whether Brinkley will remain on the case.

After the feud between Williams and Brinkley erupted, with Williams accusing the judge of being enamored with him and claiming that the FBI had investigated her handling of the case, Williams' attorneys repeatedly sought to have her removed from the case.

The Supreme Court's decision Wednesday denied Williams' request, but said Brinkley could still “opt” to remove herself. Attorneys agreed that Williams' counsel could continue pushing the issue, but, as Fairlie said, “They may well ask for it again, but I don't see how the decision would be any different because nothing has changed.”

Regarding how prosecutors may handle any retrial of Williams, the district attorney's office has declined to comment. However, in three case involving Graham, the defendants have recently walked free.

Last week, Philadelphia's First Judicial District President Judge Sheila Woods-Skipper granted similarly unopposed PCRA petitions for those defendants, and the prosecutors subsequently dropped the charges. Similar PCRA petitions involving Graham are pending in more than 100 cases, according to court officials.

Defense attorney Stan Lacks said that, while many cases involving Graham may eventually be withdrawn, prosecutors and the courts are still going to thoroughly review the cases to see how Graham's role impacted the trial.

“Each case is being looked at on a case-by-case basis,” Lacks said. ”It's not going to be automatic.”

But if prosecutors decide not to bring charges, Brinkley's hands are all but tied, defense attorneys agreed.

“The judge could say, 'I'm not agreeing to nolle pros the case,' and they could say, 'That's fine, but we're not prosecuting the case,' and then the judge has effectively been trumped,” Fairlie said. “There's no way for the judge to try the case herself.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250