In Latest Appeal, Mumia Abu-Jamal Claims Ex-Pa. Justice Castille Was Biased

Former death-row inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal, convicted for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner, has asked a Philadelphia judge to give him the chance to appeal yet again.

April 30, 2018 at 02:33 PM

4 minute read

Former death-row inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal, convicted for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner, has asked a Philadelphia judge to give him the chance to appeal yet again.

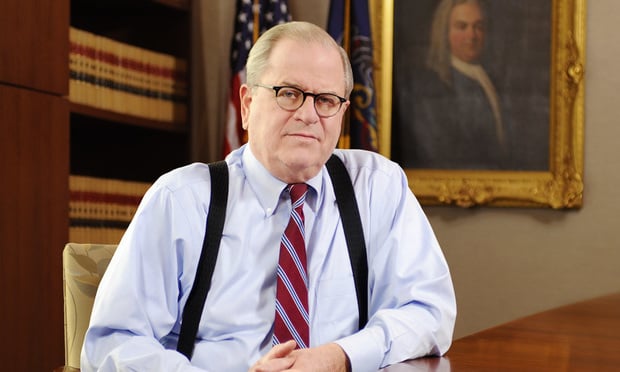

In the latest chapter of the 37-year saga that is the Abu-Jamal case, defense attorneys on Monday argued that former Philadelphia District Attorney Ronald D. Castille, who oversaw prosecutors' response to Abu-Jamal's appeal in the early 1990s, should not have weighed in on those same issues as a justice of the state Supreme Court years later.

Abu-Jamal, formerly Wesley Cook, was absent from the courtroom packed with supporters and members of the Fraternal Order of Police. His lawyers asked Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas Judge Leon Tucker to vacate Abu-Jamal's previous failed appeals, which would clear the way for a new bid for freedom.

Abu-Jamal's lawyers claimed Castille was biased and viewed Abu-Jamal as a “cop killer.” Conversely, prosecutors argued that Castille did not have extensive personal involvement in the case as a district attorney.

Monday's hearing centered on a missing memo from 1990 in which Castille apparently asked then-Assistant District Attorney Gaele Barthold for information on capital murder cases to send to then-Gov. Robert Casey urging the acceleration of executions for death-row inmates. Abu-Jamal's defense team claims that the memo shows Castille took a special interest in death-penalty cases, especially those involving murdered police.

Assistant District Attorney Tracey Kavanagh told Tucker that a paralegal in the office searched extensively for the memo, but came up short. Additionally, Kavanagh said that Castille did not exercise critical decision-making in Abu-Jamal's case—unlike in the underlying prosecution in Williams v. Pennsylvania, a 2016 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Castille, who signed defendant Terrance Williams' death warrant while he was district attorney, should have recused himself when the matter came before him as a justice.

The U.S. Supreme Court's majority opinion, which was written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, said that, “Under the due process clause there is an impermissible risk of actual bias when a judge earlier had significant, personal involvement as a prosecutor in a critical decision regarding the defendant's case.”

At the Abu-Jamal hearing, Tucker granted the parties' request to depose Barthold and also reach out to Castille to obtain the missing memo in question, pushing back the next court date in the case to Aug. 30.

However, in an interview with The Legal on Monday, Castille said he doesn't remember writing the memo and claimed he does not possess it.

“I have no idea what they're talking about,” Castille said, adding that he communicated with Casey outside of his role as district attorney. “As legislative liaison, I represented the DA's association and Casey would not sign any of those death warrants. The DA's association thought he was against it, so any contact I had with Casey would be part of the DA's association.”

Regarding the Abu-Jamal case, Castille said, “As DA I didn't have anything to do with it until it went up on appeal.” He added, “none of them ever asked me to recuse myself on appeal when I was a justice. To me it was just another case.”

The controversial case is seen as a test of the reform agenda of current District Attorney Larry Krasner, who has called for a hard look at hundreds of prosecutions post-conviction.

However, Faulkner's widow, Maureen Faulkner, said she thinks Krasner won't depart from his office's traditional stance on the case.

Outside Philadelphia's criminal courthouse after the hearing, Faulkner, who now lives in California, said she believes that once Krasner has more experience on the job, he'll walk back his reform efforts.

“District Attorney Krasner will see more and more crime and more and more murders and he'll have to speak up for the victims,” Faulkner said.

District Attorney's Office spokesman Ben Waxman reiterated Monday, “Our position this morning in court is that we did not believe there was a due process violation … in our view this was not a case where the standard was met” as in the Williams case.

“We also came to the conclusion that Castille in this case did not have the personal involvement that would result in a due process violation,” he added.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Lawsuit Against Major Food Brands Could Be Sign of Emerging Litigation Over Processed Foods

3 minute read

Kline & Specter and Bosworth Resolve Post-Settlement Fighting Ahead of Courtroom Showdown

6 minute read

'Discordant Dots': Why Phila. Zantac Judge Rejected Bid for His Recusal

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250