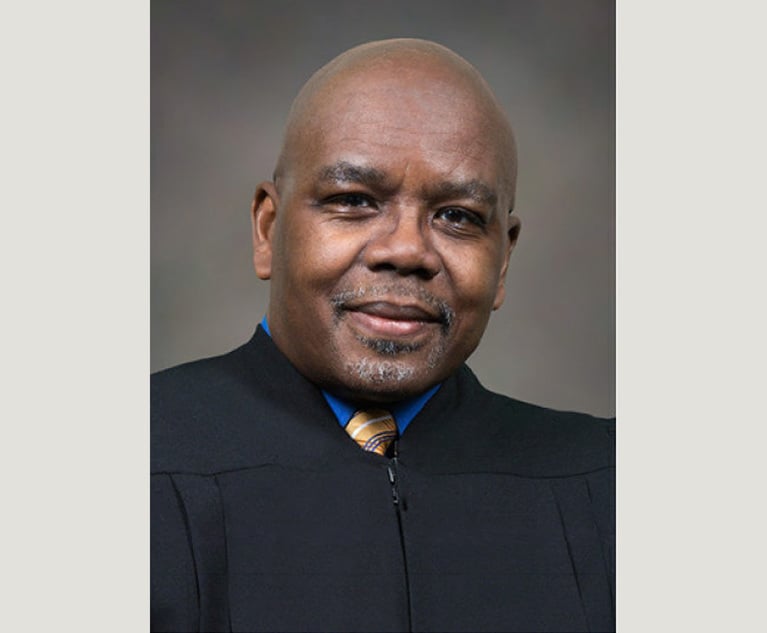

U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah, D-Pennsylvania, at a hearing Jan. 26, 2016. Photo: P.J. D'Annunzio

U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah, D-Pennsylvania, at a hearing Jan. 26, 2016. Photo: P.J. D'AnnunzioEx-Congressman Fattah's Bribery Convictions Overturned, Eligible for Retrial

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held Thursday that Fattah and wealthy friend Herbert Vederman should have a second chance on multiple bribery-related counts of the indictment against them, which allege a scheme involving Fattah trying to secure an ambassadorship for Vederman, among other things.

August 09, 2018 at 11:04 AM

5 minute read

A federal appeals court has ruled that Chaka Fattah and an associate are eligible for a new trial on several bribery charges because the jury that convicted him in 2016 was improperly instructed on the law.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held in a 142-page opinion released Thursday that Fattah and wealthy friend Herbert Vederman should have a second chance on multiple bribery-related counts in the indictment against them, which alleges a scheme involving Fattah trying to secure an ambassadorship for Vederman, among other things.

At the same time, the court also reinstated two previously overturned convictions on Fattah and Vederman's involvement in bank fraud and making false statements to financial institutions.

The rest of Fattah's convictions also stand, the Third Circuit held.

Chief Judge D. Brooks Smith wrote in the court's opinion that U.S. District Senior Judge Harvey Bartle III of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania gave faulty instructions to the jury on what constitutes an “official act” done for money or gifts in a bribery case—a holding stemming from the U.S. Supreme Court's game-changing decision in McDonnell v. United States.

The McDonnell decision essentially makes it harder for prosecutors to score convictions against public officials because it narrows the definition of what can be considered an official act. The alleged official acts at hand in Fattah's case deal with the former congressman setting up a meeting between Vederman and then-U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk, his attempts to secure Vederman an ambassadorship, and his hiring of Vederman's girlfriend to his staff, in return for bribes.

“In this case, as in McDonnell, the jury instructions were erroneous. We conclude that the first category of the charged acts—setting up a meeting between Vederman and the U.S. trade representative—is not unlawful, and that the second category—attempting to secure Vederman an ambassadorship—requires reconsideration by a properly instructed jury. The third charged act—hiring Vederman's girlfriend—is clearly an official act. But because we cannot isolate the jury's consideration of the hiring from the first two categories of charged acts, we must reverse and remand the judgment of the district court,” Smith said.

Fattah's lawyer, Bruce Merenstein of Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis, declined to comment.

William McSwain, U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, said the office is reviewing to see what course of action to take.

“The government will carefully study the matter and determine whether the interests of justice warrant a retrial of the counts related to the Vederman bribery, or whether it is sufficient to dismiss those counts in light of the fact that both Fattah and Vederman remain convicted of serious federal crimes that in our view warrant the full sentences that were previously imposed,” McSwain said.

Fattah, 61, is currently serving a 10-year prison sentence in a federal correctional facility in McKean County. Vederman, a former Philadelphia deputy mayor in the Ed Rendell administration, was given a two-year prison sentence. It is unclear how the Third Circuit's ruling will affect those sentences.

White-collar criminal defense lawyer Linda Dale Hoffa, former Criminal Division chief at the U.S. Attorney's Office in Philadelphia, said the ruling was essentially a draw for both sides—but it could lead to a plea deal.

“This allows the possibility for the government and the defense to see if they want to negotiate some resolution,” Hoffa said.

Otherwise, it's up to the prosecutors whether they want to move forward with a retrial, or let the vacated convictions and reinstated ones stand as they are.

In a previous ruling, Bartle said Fattah's attempt to secure Vederman an ambassadorship was an obvious official act.

“The evidence here established overwhelmingly that Fattah was engaged in official acts as defined in [McDonnell] in his persistent quest for an ambassadorship for Vederman,” Bartle said in his a lengthy opinion in October 2016. “The appointment of an ambassador is a specific and focused exercise of governmental power. Fattah's aim was to obtain a high government post for a particular person, that is Vederman. It is hard to be more specific and focused than this.”

In June 2016, Fattah was found guilty of all 22 charges against him after a month-long corruption trial and three days of deliberation. He was convicted of using grant funds to repay $600,000 of an illegal million-dollar campaign loan from his failed 2007 Philadelphia mayoral bid, taking bribes, paying off his son's student loan debt with campaign money, obstruction of justice, and money laundering.

During his sentencing hearing in December 2016, assistant U.S. attorney Eric Gibson emphasized that the Philadelphia Democrat's crimes were not “victimless offenses.”

Gibson told the court that Fattah “knew what he was doing” over the seven-year period of the scheme, from 2007 until the indictment. Fattah's efforts to provide educational opportunities to students from low-income families over his 20-year tenure, and his work in advancing neuroscience, were “far outweighed by the abuses [of power] he engaged in for his personal benefit,” Gibson added, arguing that while many people in Fattah's district couldn't afford homes of their own, the ex-congressman was taking bribes to pay for his vacation home in the Poconos.

Fattah's 10-year sentence was one of the harshest ever imposed on a American politician; as it stands, former U.S. Rep. William Jefferson, D-Louisiana, holds the record for the stiffest sentence. Jefferson, of New Orleans, is currently serving a 13-year prison term for bribery. Jefferson, who was sentenced to his prison term in 2009, was noted for hiding $90,000 in cash in his freezer.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Plaintiffs Seek Redo of First Trial Over Medical Device Plant's Emissions

4 minute read

Remembering Am Law 100 Firm Founder and 'Force of Nature' Stephen Cozen

5 minute read

Eckert Seamans Snags Reed Smith Global Financial Intelligence Director

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Call for Nominations: Elite Trial Lawyers 2025

- 2Senate Judiciary Dems Release Report on Supreme Court Ethics

- 3Senate Confirms Last 2 of Biden's California Judicial Nominees

- 4Morrison & Foerster Doles Out Year-End and Special Bonuses, Raises Base Compensation for Associates

- 5Tom Girardi to Surrender to Federal Authorities on Jan. 7

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250