Longest-Serving Philadelphia Court Employee Has Probably Handled Your Divorce

Dennis O'Connell, 70, has been a divorce master for 30 years out of his 45-year career in the Philadelphia court system.

August 14, 2018 at 04:29 PM

5 minute read

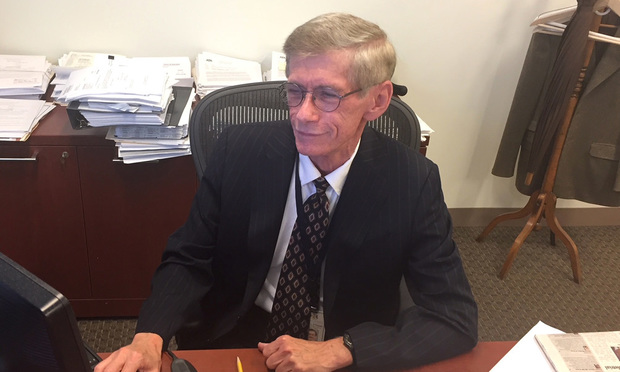

Dennis L. O'Connell, divorce relations master, Court of Common Pleas, Family Court Division, in Philadelphia.

Dennis L. O'Connell, divorce relations master, Court of Common Pleas, Family Court Division, in Philadelphia.

If you were to meet Dennis O'Connell on the street, you'd likely not assume the slender, soft-spoken man has the power to dramatically alter the course of a person's life.

But if you're sitting across from him in a hearing room at the Philadelphia Family Courthouse, you'll soon realize he is to be taken seriously. That's because he decides who gets the house, car—and maybe even the dog—in your divorce.

O'Connell, 70, has been a divorce master for 30 years out of his 45-year career in the Philadelphia court system. While divorce master sounds like a title that could be given to Larry King, in the Philadelphia Family Court it's a lawyer who specializes in splitting a couple's assets, determining if alimony is appropriate, and generally putting the finishing touches on a divorce.

By the time a case crosses his desk, spouses have been separated for years and the intensity of any lingering acrimony between them has generally died down, but that doesn't mean shepherding exes through the division of assets is a walk in the park.

“I hope I never get jaded, but I think I've heard just about everything over the years,” O'Connell said in an interview with The Legal.

The Pottstown native had different plans for his future when he was a student, originally envisioning a career as a reporter. O'Connell was the editor for his high school and college newspapers and worked as a stringer for several Montgomery County local papers before having a change of heart while studying history at Ursinus College.

O'Connell graduated with his law degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1973. During his time at Penn he worked for a class action law firm in the city but decided that type of work wasn't for him. It was several months after he graduated, when he began clerking for then-head judge of the family court, Judge Nicholas Cipriani, that O'Connell found his niche in life.

He continued clerking for judges until 1988, when the family court did away with the private divorce master system and he took a job as one of the newly minted court-employed masters.

O'Connell said his job is largely an exercise in economics. He examines assets and determines who should get what—for example, how to split a pension. To do that he goes over the parties' court papers and financial records with a fine-tooth comb. He also uses a really big calculator.

“To supplement, I may ask questions on the day of the hearing, but by that time I will have reviewed the documentation. After hearing brief testimony I will take a recess and I will make a recommendation for a settlement. That recommendation is based on my experience in years of cases. In over 90 percent of cases we get a settlement, usually on the same day,” O'Connell said.

But in some of the cases O'Connell handles, it can take up to a week for the parties to reach an agreement.

And of course, not everyone is happy with the result. In fact, it's normal for both parties to walk away from the proceedings at least somewhat disappointed.

“The stakes are high in these cases,” O'Connell said. “The parties come in with their own conceptions of what the result should be.” However, the goal, he said, is not for there to be a winner and a loser but “to allow people to move on with their lives.”

That part of the job hasn't changed over the decades. But certain other aspects naturally have, including the number of divorces overall.

“For one thing, I've noticed a decline in the number of cases,” O'Connell said. “When I first started hearing divorce cases we were processing nearly 4,000 divorces a year in Philadelphia; now it's less than half.”

He attributes that trend to a declining marriage rate. “You can't get divorced if you're not married.”

He has also noticed that these days people are more likely to show up to proceedings in sweatpants than in years past.

“People used to come dressed up, men in suits, women in dresses, and now it's much more casual,” O'Connell said. “But that makes no difference in the outcome.”

On the other side of the coin, O'Connell said divorce lawyers in Philadelphia are sharper than ever.

“We've always had very fine attorneys, but the degree of professionalism has heightened,” he said. “They're always well prepared. I think it's because there was a time when the law was less well-developed during the early days of our current divorce code, but now there's a very well-established body of law.”

The biggest question of all, however: Does O'Connell—a man who has worked on nothing but divorces for the past three decades, has seen the results of relationships gone down in a fiery wreck, and watched as former lovers bicker over the value of beachfront property—still believe marriage is a worthwhile endeavor?

“Absolutely,” he said.

Although O'Connell is unmarried himself, he insists it's not because he's jaded from years on the job. In fact, he remains as enthusiastic about his work now as he was on his first day as a divorce master.

“I have no plans to retire. I get a sense of satisfaction out of crafting these resolutions,” he said. “People come in here out of very unhappy circumstances and if at the end of the day I can help them move on with their lives, I feel I've accomplished something.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pa. Federal District Courts Reach Full Complement Following Latest Confirmation

The Defense Bar Is Feeling the Strain: Busy Med Mal Trial Schedules Might Be Phila.'s 'New Normal'

7 minute read

Federal Judge Allows Elderly Woman's Consumer Protection Suit to Proceed Against Citizens Bank

5 minute read

Judge Leaves Statute of Limitations Question in Injury Crash Suit for a Jury

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1‘High Demand’: Former Trump Admin Lawyers Leverage Connections for Big Law Work, Jobs

- 2Considerations for Establishing or Denying a Texas Partnership to Invest in Real Estate

- 3In-House AI Adoption Stalls Despite Rising Business Pressures

- 4Texas Asks Trump DOJ to Reject Housing Enforcement

- 5Ideas We Should Borrow: A Legislative Wishlist for NJ Trusts and Estates

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250