Commerce Court Leader Talks New Initiatives, Juggling Roles and Why the Commerce Program Is for 'Nerds'

The Legal talked with Judge Gary Glazer, head of Philadelphia's Commerce Court, about the Commerce Court program, new initiatives he plans to undertake and why the program is for "nerds."

September 05, 2018 at 04:50 PM

10 minute read

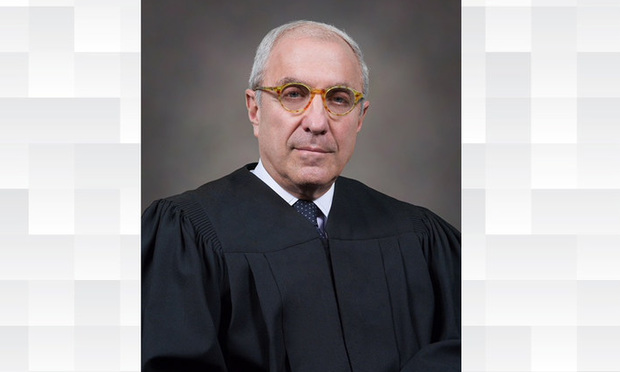

Philadelphia Judge Gary Glazer.

Philadelphia Judge Gary Glazer.

In his more than six years as a member of Philadelphia's Commerce Court program, Judge Gary Glazer approved the city's high-profile sweetened beverage tax, handled the insurance dispute regarding the victims of convicted serial child molester Jerry Sandusky and made rulings in countless law firm breakups.

Now, the longtime Philadelphia judge has taken over as head of the Commerce Court, which handles some of the city's most high-profile cases. Glazer stepped into the role over the summer after former Philadelphia Judge Patricia McInerney stepped down to do alternative dispute resolution.

The Legal talked with Glazer about the Commerce Court program, new initiatives he plans to undertake and why the program is for “nerds.”

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What has your role been previously on the Commerce Court?

I have been on the Commerce Court, I believe, since about March or April of 2012, and I was just another member of the court, hearing cases and deciding cases.

Simultaneously, I have been the administrative judge in the Traffic Court, overseeing that forum. So I've kind of always worn two hats in my time, and now I'm wearing three hats.

With your role overseeing the Municipal Court's traffic division, how is that going to interact with your new duties supervising the Commerce Court?

Well, I'm doing a lot of juggling. My typical day, when I'm not on trial, is to spend most of the day on the commerce program. But I then go to 8th and Spring Garden in the afternoon, which I'm doing today. I don't do that every single day, but I do that many days.

I do not hear cases there. I did early on, but I don't do that anymore.

What is your role going to be on the Commerce Court?

There are a fair number of admin duties involved. I oversee what cases go into the Commerce Court, what cases go out of the Commerce Court. I tend to be the liaison in matters involving tax sequestration, which is part of the Commerce Court. Those are cases filed by the city that involve delinquent real estate taxes of commercial properties, and those are probably going to be doubling in number.

I also am overseeing the taxicab program that we have. That is a program that was started about eight to nine months ago that relates to foreclosures of taxicab medallions. It's very interesting because, with Uber and Lyft, the value of taxicab medallions has decreased significantly, and many taxicab owners have taken out loans based upon the original value of the medallions, which probably were worth 10 times what they are now. And many of the drivers had taken out personal guarantees, so we kind of stole a page from the mortgage foreclosure program and tried to adapt it to the taxicab problem in the city. It's not an identical problem, but it's comparable. We're trying to keep the taxicabs going and making sure the debts get paid, and that's been a very, very interesting experience.

What is the criteria for bringing a case into Commerce Court versus the regular track?

The commerce program is for a very specific type of case. It's generally a business case of some nature, with a minimum amount of $50,000 at issue. They are business-to-business cases, so the criteria talks about complex disputes involving, but not limited to, corporate shareholders, business dissolutions, sales of businesses, confessions of judgment in the commercial context, contract disputes of all nature, construction disputes, insurance questions, declaratory judgments. I've been dealing with a lot of re-insurance questions. There's professional, non-medical malpractice, like accounting or legal malpractice.

They're business cases. They're not consumer cases—although, one little carve-out, we have just resumed handling some consumer class action cases, just because they tend to be a little more complex. But more often than not, they're relatively complex business cases, and usually there are fairly significant dollar amounts. Not always, but that's in the eye of the beholder.

How does a case get sent to Commerce Court?

It can be filed as a commerce case. In the filing sheet it says it's commerce. But every case is reviewed by our very competent case managers, who are law clerks as well. Also I get a fairly significant number of management dispute issues where one party will say this case was filed in the trial division, in major jury, but it really is a commerce case. Then we review it, and based on the recommendations, I would then decide if it comes here, or if it doesn't.

Do a lot of cases get rejected?

Just yesterday, there was a case we had originally transferred in that had three related cases that we didn't know about. When we became aware of the other three, it turns out that those were really product liability cases that we don't do, so we sent the other case back and didn't accept the other three.

And on occasion a case will, following a review of, for example summary judgement, a case will become much smaller and we'll send it to arbitration. Not every day. but it certainly does happen. There is some movement between the programs, and we always are looking and keeping an eye out to make sure that a case that should be here stays here or comes in here, or if it shouldn't be here, we send it back. We try to be very vigilant about that.

How is a case handled differently when it goes through Commerce Court versus the major jury program?

The biggest difference is the judges have individual dockets. We have a case and we handle it from the time a complaint is filed until the case is concluded, including on appeal. So we will have a case every step along the way. We will see every motion in the case. We will oversee discovery in the case. We will do the trial of the case. We will handle the opinion. We manage it every step along the way, whereas in the other programs, there tends to be various judges involved at various points in the case, and that's because of the volume.

Why does Commerce Court have individual dockets for judges?

It was felt that these types of cases, because of their complexity, factually and legally, would be better handled by one judge, and the bar was incredibly supportive and remains so of the program. The judges that are attracted to the program tend to be nerds who like that sort of thing.

I'm struggling over an opinion now that is incredibly nuanced, and we're digging deep into English law and American law. But it's that sort of thing that kind of motivates you to get involved in this program.

It's always an interesting contrast between Traffic Court and Commerce Court, being on what was, I'm going to emphasize what was, one of the most troubled and least respected courts and one of the most respected courts at the same time. It's kind of an interesting career path, but the traffic division is a much different place now. I just want to add that. It's very different than what it was.

Do you plan to handle things differently than Judge McInerney?

I wouldn't say differently. She and I had numerous and frequent discussions about expanding the diversity of our judge pro tem. We have about 100 volunteer lawyers, who perform just fabulous work in settling cases and in serving as discovery masters, and they do it really as a service to the court. But she and I both agreed that we need to kind of open the books. We need more women, we need more minority leaders to participate in this program. I have started to reach out and will be going to the bench bar conference to further reach out. We'd like to get the word out that we need more participation from more diverse members of the bar. We're missing out on a huge talent pool.

I also have an interest in the international area. I have gotten involved, and it's just in the very early stage, in something called the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts.

This is an organization that started in March 2017 in London. I was over there in the summer and I met with one of the judges who's very involved in it. There's only three courts in the U.S. that are involved in it—the Delaware Court of Chancery, the Southern District of New York, and the New York Supreme Court, as well as courts in England, Ireland, France, Germany, Africa, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, China, Japan. So I learned about this from a lawyer in Philadelphia named Lee Applebaum, and I reached out to the people in London—I was there anyways because I teach a CLE out there over the summer—and I met with this judge and I'll be going to New York at the end of September to see what it's about, see what it's like, see if there's a place for us.

It's a consortium of judges from across the world to talk about best practices, case management, about if there's a way to coordinate our efforts if appropriate, how we could assist emerging countries in developing their commerce courts.

How has it been going the past few months?

It's been wonderful, both judges [Judge Nina Wright Padilla and Judge Ramy Djerassi] are just delightful to be around and work with. We have lunch once a week when we're all here, which is usually, but not always. We have always been, we tend to get along fairly well. There's always little disputes from time to time, which is normal, but it's a very collegial group. We also have terrific law clerks who are experienced, and will advise us and assist us, and who also function as case managers too, so they review these cases as they come in.

Over the past few years, you'd handled a number of high-profile cases, including the insurance dispute involving Penn State over the settlements with the victims of Jerry Sandusky and, more recently, the Philadelphia soda tax. But from your perspective, what's the most memorable case you've handled?

Those cases are really interesting, but I tend to enjoy the cases that affect definable human interests, like a business that breaks up and the people are at each other's throats, and you get them to resolve their disputes and just walk away and get on with their lives. Most of the cases you never read about, but those are the ones that impact people, like a law firm breakup or a medical practice breakup. I had a manufacturing company that broke up and it's very much like a divorce. You're dealing with intense emotions, dividing up property, trying to get the parties to resolve their dispute before they spend any money they have and everyone walks away with nothing, which is the result I try to avoid all the time.

The other cases, they're interesting, they're fun, they're very challenging, but it's the cases that involve the people who are there in front of you that get you the most.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Ozempic Defendants Seek to Shave 'Tacked On' Claims From MDL Complaint

3 minute read

Lawsuit Against Major Food Brands Could Be Sign of Emerging Litigation Over Processed Foods

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1After Botched Landing of United Airlines Boeing 767, Unlikely Plaintiff Sues Carrier

- 2DOT Moves to Roll Back Emissions Rules, Eliminate DEI Programs

- 3No Injury: Despite Proven Claims, Antitrust Suit Fails

- 4Miami-Dade Litigation Over $1.7 Million Brazilian Sugar Deal Faces Turning Point

- 5Trump Ordered by UK Court to Pay Legal Bill Within 28 Days

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250