City to Roll Back Civil Forfeiture and Compensate Philadelphians Affected by It

The settlement was announced Tuesday morning and concludes a 2014 federal lawsuit filed by the Institute for Justice, which had brought the case on behalf of Chris Sourovelis and several other plaintiffs who have had property taken by law enforcement through civil forfeiture.

September 18, 2018 at 12:38 PM

3 minute read

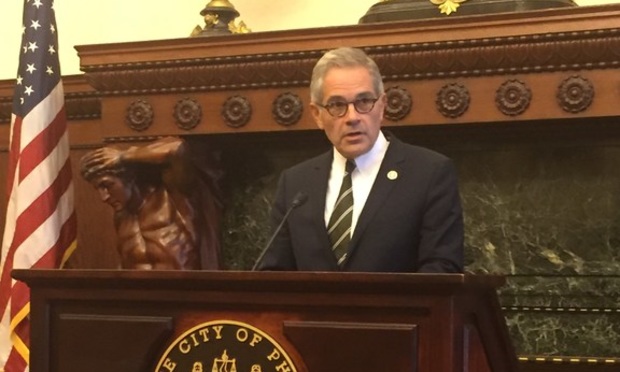

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner. (Photo: P.J. D'Annunzio/ALM)

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner. (Photo: P.J. D'Annunzio/ALM)

The city of Philadelphia has agreed to stop allowing law enforcement to profit from civil forfeiture, a controversial practice involving the seizure and sale of private property from a criminal suspect. The city has also agreed to set up a $3 million fund to compensate those affected by it.

The settlement was announced Tuesday morning and concludes a 2014 federal lawsuit filed by the Institute for Justice, which had brought the case on behalf of Chris Sourovelis and several other plaintiffs who have had property taken by law enforcement through civil forfeiture.

The terms of the settlement dictate that the city cannot seize property for minor drug crimes like possession, will not forfeit cash in amounts less than $250, and will not use any proceeds to pay police officers or prosecutors, to name a few conditions.

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney and District Attorney Larry Krasner, along with other officials gathered at a City Hall press conference Tuesday afternoon, lauded the near-total abolition of civil forfeiture in the city.

Kenney said the settlement etches in stone the city's 2017 decision to extinguish the practice.

“This is a good resolution,” the mayor said, “because it reforms a system that, left unchecked, can prey upon the most vulnerable.”

“This settlement agreement was a long time coming, and something that our city needs to move our criminal justice reform efforts forward,” Krasner said. ”We will no longer use civil asset forfeiture to take grandma's possessions because her grandchild got into a little bit of trouble.”

However, Krasner noted the practice would continue to be used in cases involving drug houses owned by criminal enterprises.

Law enforcement agencies in Philadelphia have made as much as $1 million per year through civil forfeiture, according to an American Civil Liberties Union report. However, they will not be greatly impacted by the absence of those funds, according to Philadelphia Police Commissioner Richard Ross, because law enforcement has been weening itself off of that money since before the practice was pared down.

“It's not really going to affect the way we do business,” Ross said.

City Solicitor Marcel Pratt said the settlement was the product of four years of legal wrangling and negotiations between both sides.

Darpana Sheth, a senior attorney at the Institute for Justice and point-person in the institute's anti-civil forfeiture effort, said in a statement: “For too long, Philadelphia treated its citizens like ATMs, ensnaring thousands of people in a system designed to strip people of their property and their rights. No more. Today's groundbreaking agreement will end years of abuse and create a fund to compensate innocent owners.”

Sourovelis, who according to the institute nearly lost his house after his son was arrested for selling $40 worth of drugs, praised the settlement.

“I'm glad that there is finally a measure of justice for people like me who did nothing wrong but still found themselves fighting to keep what was rightly theirs,” Sourovelis said. “No one in Philadelphia should ever have to go through the nightmare my family faced.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Discordant Dots': Why Phila. Zantac Judge Rejected Bid for His Recusal

3 minute read

Phila. Court System Pushed to Adapt as Justices Greenlight Changes to Pa.'s Civil Jury Selection Rules

5 minute read

Pa. Appeals Court: Trial Judge Dismissed Med Mal Claims Without Giving Plaintiffs Proper Time to Fight Back

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250