Judge Enforces Disputed $125M Settlement Over Provigil

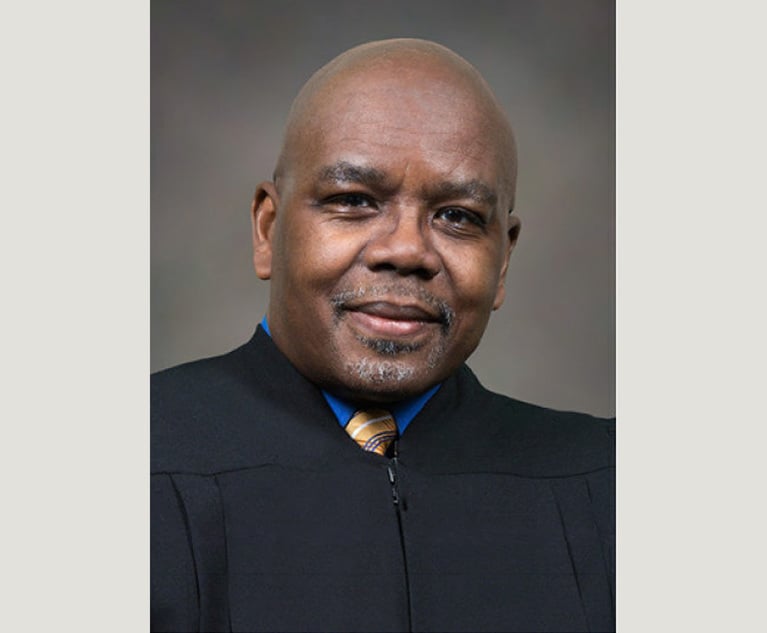

U.S. District Judge Mitchell Goldberg of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania ruled Wednesday that a 2015 memorandum of understanding between United HealthCare Services and three drug companies was binding.

September 19, 2018 at 04:10 PM

4 minute read

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Outside counsel for United HealthCare Services had been given the authority to enter into a $125 million settlement with the makers of the sleep-disorder drug Provigil, a federal judge has ruled in finding that the accord settling antitrust claims is enforceable.

U.S. District Judge Mitchell Goldberg of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania ruled Wednesday that a 2015 memorandum of understanding between United and three drug companies was binding. The decision rejected efforts by United to back out of the accord over claims that, among other things, the company never gave its outside counsel authority to enter into a binding settlement.

Although Goldberg said he agreed that the company never gave its outside lawyers express authority to enter into the settlement, he said facts presented during a recent bench trial indicated that United had “cloaked” its outside counsel in the “apparent authority” to settle the claims.

“United—a major health insurance company with a deep and experienced bench of in-house lawyers—decided to hire outside counsel to conduct all settlement negotiations on its behalf on the Provigil litigation,” Goldberg said. “In doing so, United placed complete authority in outside counsel to act on its behalf in these negotiations without providing outside counsel any parameters.”

The $125 million settlement is part of a much broader antitrust litigation over Provigil, which included a claim by a separate generic drug company, a $1.2 billion settlement with the Federal Trade Commission and suits brought by direct purchasers of the drug. United, which is a third-party payer, was part of the litigation brought by indirect purchasers of the drug.

According to Goldberg, the indirect purchasers entered into the accord in late 2015, after class certification for third-party payers had been denied. The agreement said that Cephalon, which was the brand manufacturer of Provigil, and generic drug companies Teva and Barr Pharmaceuticals would pay $48 million to settle with end-payors and $77 million to settle claims brought by third-party payers.

Settlement negotiations, according to Goldberg, were handled by, among others, Kirkland & Ellis New York partner Jay Lefkowitz on behalf of the drug companies and Richard Cohen of Lowey Dannenberg in White Plains, New York, on behalf of the third-party payers. United outside counsel included Mark Sandmann and Pamela Slate of Hill, Hill, Carter, Franco, Cole & Black, Goldberg said.

According to Goldberg, United's outside counsel dealt mostly with Cohen, and did not deal with Cephalon's counsel directly regarding the settlement negotiations.

About six months after the memorandum of understanding was signed in December 2015, United told the drug companies it did not consider itself bound by the settlement, and fired its outside counsel.

In April, Goldberg rejected United's attempts to invalidate the accord. The company had contended that language in the agreement, including the use of the word “will” instead of “shall,” was speculative and ambiguous.

Goldberg rejected those claims, finding instead that the agreement was clear, but said the case should proceed to trial on whether United's outside counsel had authority to enter into the agreement, and whether the company promptly disputed whether the accord was binding.

Regarding the arguments about whether United promptly objected to the accord, Goldberg noted that, although the company had the agreement by January 2016, it did not begin to raise concerns until March 2016. That three-month delay and the company's decision to rely on outside attorneys showed that United effectively ratified the agreement, Goldberg said.

“In short, four of United's in-house lawyers received the MOU in mid-January, but chose either to not read it at all or to rely almost exclusively on outside counsel's interpretation. A sophisticated company ably represented by a team of in-house lawyers cannot remain willfully blind to a contractual obligation and then claim that their ignorance precludes ratification,” Goldberg said in the 84-page opinion. “The MOU was a brief, six-page, double-spaced document containing unambiguous language expressly indicating in plain language that the settlement was binding and enforceable. Once United's in-house lawyers had the MOU in hand, United had full knowledge of the material facts and circumstances regarding the transactions to be ratified.”

Abby Dennis of Boies Schiller & Flexner, who is representing United, did not return a call seeking comment. Bradley Weidenhammer of Kirkland & Ellis is representing the drug companies. He declined to comment without first speaking with his client.

Read More

Judge Keeps $125M Provigil Settlement Intact, Denying Claim Document Wasn't Final

3rd Circuit Reinstates Heart Device Maker's Antitrust Suit Against Health Insurers

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Discordant Dots': Why Phila. Zantac Judge Rejected Bid for His Recusal

3 minute read

Pittsburgh Jury Tries to Award $22M Against J&J in Talc Case Despite Handing Up Defense Verdict

4 minute read

Plaintiffs Seek Redo of First Trial Over Medical Device Plant's Emissions

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250