Welcome to the Border: Asylum Seekers in the Trump Era

When I recently visited the border crossing between El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, at the Las Americas Bridge over the Rio Grande, I saw a wholly different reality: two communities so integrated that port-of-entry commuter traffic rivaled Philadelphia's Schuylkill Expressway, and dozens of students chatted warmly as they walked from their high school on the U.S. side to their family homes in Juarez.

January 11, 2019 at 01:58 PM

5 minute read

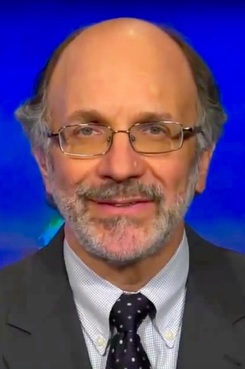

Students from Bowie High School, which is located in El Paso, Texas, just yards from the border, walk home across the Las Americas Bridge to Juarez, Mexico. Photo by Frank P. Cervone

Students from Bowie High School, which is located in El Paso, Texas, just yards from the border, walk home across the Las Americas Bridge to Juarez, Mexico. Photo by Frank P. Cervone Frank P. Cervone, Support Center for Child Advocates

Frank P. Cervone, Support Center for Child Advocates

If you believe the rhetoric, the U.S.-Mexico border is a repugnant and dangerous place roiling with unseemly people sneaking into our country, smuggling drugs and escaping law enforcement. When I recently visited the border crossing between El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, at the Las Americas Bridge over the Rio Grande, I saw a wholly different reality: two communities so integrated that port-of-entry commuter traffic rivaled Philadelphia's Schuylkill Expressway, and dozens of students chatted warmly as they walked from their high school on the U.S. side to their family homes in Juarez.

The idea that we need to build a wall to protect ourselves is mocked by the reality of border communities that have been more together than apart for generations. In fact, the people who need protection are the migrants and refugees who are seeking safe haven here, as documented in a recent report called “Sealing the Border: Criminalization of Asylum Seekers in the Trump Era.”

The report, published by the Catholic social justice organization Hope Border Institute in El Paso (www.hopeborder.org), focused on troubling violations of human rights and due process, such as: punitive customs actions including the forced separation of young children from their parents; harsh and inhumane conditions in the detention centers; severely delayed proceedings conducted without the right to counsel or translation for indigenous Central Americans; and federal immigration judges who virtually never rule in favor of the asylum applicant.

Data indicate that El Paso is one of the hardest places to receive justice in the immigration courts, where judges rule against Mexican and Central American asylum seekers nearly 100 percent of the time. But justice is hardly more forthcoming elsewhere on the border: a nationwide backlog of more than 650,000 cases and a denial rate above 70 percent, triple the rate for Asian and African asylum applicants.

The so-called “Iron Triangle of Deterrence” of border patrol, detention and the courts, ultimately forces migrants to choose between two harsh choices: deportation and forced return to a dangerous homeland, or extended detention that may last months or years, often separated from their children.

In two visits this past year, the Support Center for Child Advocates' training institute, the Center for Excellence in Advocacy, was invited to El Paso to train more than 200 lawyers, judges and case workers who work with migrants and refugees. We explored ways to find the compassion, energy and sanity to work with clients in crisis. Our colleague-students shared the stories of their clients: sexual assault, gangs targeting family members, children separated from parents and the despair of having no safe place to go. Vicarious trauma is a real concern for these dedicated front-line workers who feel the pain and suffering in countless tragic stories, and who often feel burnout and compassion fatigue as their trauma-response. We teach a curriculum of “self-care” so that these workers can continue to serve their clients and remain healthy themselves.

The challenge for border workers is to continue the fight for justice, when cases number in the tens of thousands and the outlook for success seems so bleak. One can imagine that the U.S. government's own workforce, from border police and customs officers to judges and detention center staff, must be feeling similarly strained. The cost is born by these workers, by their clients and by our sense of justice itself.

Asylum is a long-standing protection offered by U.S. law for those who “have a reasonable fear of persecution” in their home country. Many applicants present themselves, voluntarily and in compliance with our laws, to tell their horrifying tales of murder, rape, kidnapping and extortion.

In response, they are vilified and the border is portrayed as our only protection against them— invaders who threaten our safety and take our jobs. This warped view diminishes the inherent value of other peoples and the immeasurable contributions that immigrants have made in the modern world.

Our country has a long and impressive history of welcoming, that we should not diminish with fear-mongering or justice misapplied. Lady Liberty invites the world: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Rather than feeling threatened or burdened, why not find fulfillment and pride in a more humane treatment of immigrants?

Frank P. Cervone is executive director of Support Center for Child Advocates. Contact him at [email protected].

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pa. Federal District Courts Reach Full Complement Following Latest Confirmation

The Defense Bar Is Feeling the Strain: Busy Med Mal Trial Schedules Might Be Phila.'s 'New Normal'

7 minute read

Federal Judge Allows Elderly Woman's Consumer Protection Suit to Proceed Against Citizens Bank

5 minute read

Judge Leaves Statute of Limitations Question in Injury Crash Suit for a Jury

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250