The Use of Technology to Reduce the Cost and Scope of E-Discovery

Federal and state courts have weighed in and generally concur that e-discovery must be proportional to the matter. The question remains, what does that actually mean?

January 30, 2019 at 01:29 PM

7 minute read

(l-r) Dan Beaty of Special Counsel, Lisa Goldstein of Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney and Kristopher Wasserman of Special Counsel.

(l-r) Dan Beaty of Special Counsel, Lisa Goldstein of Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney and Kristopher Wasserman of Special Counsel.

Federal and state courts have weighed in and generally concur that e-discovery must be proportional to the matter. The question remains, what does that actually mean? With data volumes exponentially increasing in scope due to the ever-increasing use of email, texting and social media, how do lawyers create proportional, accurate responses to e-discovery requests? We delved into a side by side analysis of a discovery request utilizing two different workflow methodologies to illustrate the vast difference technology and process can have on the cost of a production. We analyzed two scenarios with the same data set. These produced starkly different economic results.

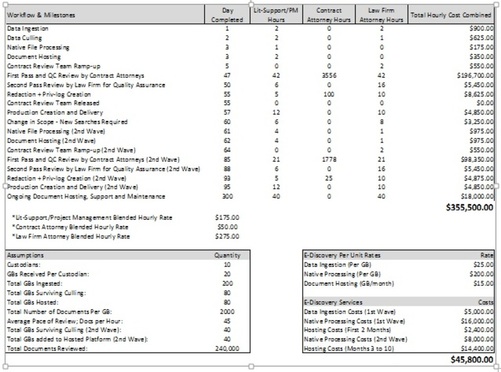

Scenario “A” followed a more traditional approach to leveraging e-discovery technology and consisted of a single matter and a full collection of custodian inboxes for 10 custodians. Prior to the collection effort, the firm negotiated key terms and date ranges with opposing counsel. The data was processed and any documents that hit on the agreed searches were promoted to a review platform. A single service provider was selected to provide the data processing, hosting, litigation support, and a team of contract attorneys to assist with the first-pass review efforts related to meeting the initial production obligations.

Scenario “B” was similar in virtually every way, however, all collected data was processed and loaded into a review platform to allow for early analysis and keyword searches to be tested prior to negotiating with opposing counsel. The same service provider was selected; however, a slightly different pricing model was applied due to the change in approach. In this scenario, because the firm elected to host all data that was processed, a flat fee of $25 per GB, monthly, was offered that incorporated all data processing, hosting and analytics fees.

With each scenario we answered the following questions:

- How long did each phase of the discovery process take? What were the total technology costs? How many hours were billed by the various disciplines necessary?

- Separately, what pitfalls were encountered due to midstream scope changes? How did these impact turnaround time and total project costs due to the additional work?

For each scenario, the tables below step through the daily discovery lifecycle with a midstream change in scope that required the team to perform additional searches to identify documents previously not considered because they were believed to be nonresponsive. In the first example, this pivot added several days to the overall effort and resulted in a full production being completed in approximately three months. In the second example, the same change in scope did not have nearly the same impact and production was completed inside of two months.

Section A

Section B

The major difference between the two approaches is the decision to promote all data into the review environment in the second example, versus only processing and hosting data that hit on search terms in the first example. In the first scenario, when the case team was required to “go back to the well,” to perform additional searches it required the service provider to process data previously left on the cutting room floor and promote it to the review environment. Prior to promoting the documents for an additional wave of review, any documents that had previously hit on the original set of search terms needed to be parsed from the population. Furthermore, because the search results could not be analyzed until the documents were published to the review environment, the volume of documents that were presented to reviewers was a bit higher because the case team chose to apply searches more broadly as a defense against future scope changes.

The second approach saw the case team spending nearly five days working within the review environment testing searches and leveraging analytics technology to increase their precision and reduce the overall number of documents presented to reviewers. They knew that if they needed to add documents to the review set, it would require a simple matter of identifying the documents and batching them out. In the first scenario, roughly 240,000 documents were reviewed, whereas in the second only 200,000 were reviewed.

The second scenario also benefited from the use of analytics during the review process. By clustering the documents into smaller batches that contained conceptually similar content and grouping all emails within a conversation thread into the same batch, the pace at which the records were reviewed increased by ten documents per hour.

Ultimately the costs for the technology were slightly lower in the first scenario; a difference of nearly $5000 in the aggregate. Had there not been a change midstream that required additional searches, the pricing model used in the first example would have been closer to $10,000 less. However, the decision by the case team to promote all data to the review environment to allow for the use of analytics technology to assist with the culling and review efforts drastically reduced the number of billable hours that were needed to garner the same end result. The slightly lower document count combined with the increase in review pace saved over $100,000 and was completed in less time.

In the early 2000s, when discovery began to see the incorporation of electronic documents in addition to paper, the technology of the day forced case teams to take the same approach that is represented in the first scenario. This methodology presents limited options for applying more precise culling strategies without incurring a cost-prohibitive bill tied to hosting data. Unfortunately, for various reasons, even though the tools available have matured, the approach towards e-discovery has changed little over the years. Many still view the technology costs associated with discovery in a vacuum and seldom consider the extra expenditure in billable hours that will result from making certain workflow decisions early in the process. More importantly, the assumption that midstream changes will not occur during the fact-finding process has proven to be a risky proposition. While no two matters are identical, virtually all data mining and discovery efforts reveal new information that ultimately influences the case strategy going forward.

In summary, the technology available with today's advanced tools requires a learning curve to properly navigate, and appears more costly without an analysis of review hours. However, when technology assisted review is properly utilized, the time required to review the data decreases, and the overall budget is less expensive.

Dan Beaty is a former practicing attorney who switched gears five years ago and moved to Special Counsel to serve as their director of strategic solutions. He consults with corporate legal departments and law firms to harness technology and project management processes to maximize the effectiveness of legal spend.

Lisa Goldstein, as the business development manager of litigation at Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney, Goldstein assists the firm's litigation lawyers with servicing existing clients and expanding their focus across core industries in the life science, energy, financial service and health care industries.

Kristopher Wasserman is vice president and senior consultant at Special Counsel. He oversees a team of solutions directors that provide technical expertise and guidance to corporate legal departments and law firms to develop defensible cost-effective solutions that involve managing and reviewing data that may be used as evidence.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pa. Federal District Courts Reach Full Complement Following Latest Confirmation

The Defense Bar Is Feeling the Strain: Busy Med Mal Trial Schedules Might Be Phila.'s 'New Normal'

7 minute read

Federal Judge Allows Elderly Woman's Consumer Protection Suit to Proceed Against Citizens Bank

5 minute read

Judge Leaves Statute of Limitations Question in Injury Crash Suit for a Jury

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Judge Pauses Deadline for Federal Workers to Accept Trump Resignation Offer

- 2DeepSeek Isn’t Yet Impacting Legal Tech Development. But That Could Soon Change.

- 3'Landmark' New York Commission Set to Study Overburdened, Under-Resourced Family Courts

- 4Wave of Commercial Real Estate Refinance Could Drown Property Owners

- 5Redeveloping Real Estate After Natural Disasters: Challenges, Strategies and Opportunities

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250