The Erosion of Due Process for Public Figures in the #MeToo Era

To what extent are the foundational concepts of due process followed when public persons are accused of sexual assault many years after the alleged conduct occurred?

February 13, 2019 at 02:10 PM

5 minute read

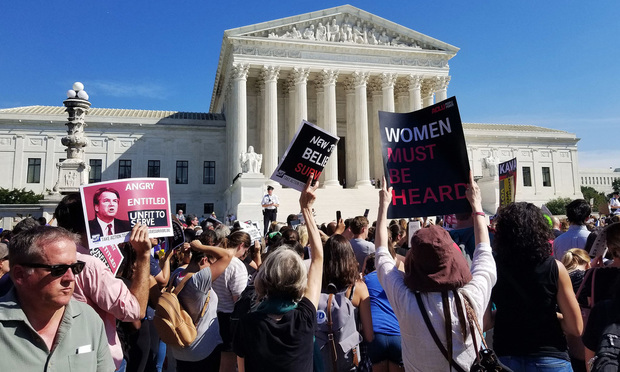

Demonstrators outside the U.S. Supreme Court protest the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh, on Thursday, Oct. 4, 2018. Photo: C. Ryan Barber/ALM

Demonstrators outside the U.S. Supreme Court protest the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh, on Thursday, Oct. 4, 2018. Photo: C. Ryan Barber/ALM

On Oct. 6, 2018, Brett Kavanaugh was sworn in as the 114th justice of the U.S. Supreme Court at a private ceremony—a stark contrast from the very public confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee that played out in the preceding weeks. Kavanaugh's confirmation was nearly derailed after Christine Blasey Ford and several other women alleged that the judicial nominee had sexually assaulted each of them in the 1980s. In the midst of the #MeToo movement, the allegations prompted nationwide outrage and daily protests against Kavanaugh, while hashtags such as #BelieveAllWomen and #WhyIDidntReport dominated social media.

Kavanaugh was eventually confirmed by a margin of only two votes, and while there have been whispers of a grassroots movement to impeach him, it appears as though nothing more will come of the allegations against him. The same cannot be said for embattled Virginia Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax. Amid recent calls for the resignation of Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam over a racist yearbook photo, Fairfax, who is next in line for the governorship, was accused of sexually assaulting a woman in 2004 during the Democratic National Convention in Boston. Fairfax immediately denied the allegations and described the encounter as consensual. Fairfax's accuser, identified as Vanessa Tyson, has retained the same group of lawyers that represented Ford. Fairfax, meanwhile, has retained the same group of lawyers that represented Kavanaugh.

A second woman has now accused Fairfax of rape dating back to their time as classmates at Duke University in 2000. In a statement released by her attorneys, Meredith Watson contends that she has a series of emails and Facebook messages corroborating that she immediately told friends that Fairfax had raped her. Calls for Fairfax's resignation have intensified to a fever pitch.

There are certainly differences between the circumstances surrounding Kavanaugh and Fairfax. For starters, the allegations against Kavanaugh were revealed when the Senate Judiciary Committee was considering his confirmation for a lifetime appointment to the country's highest court. Fairfax, meanwhile, was elected by Virginia voters to serve a four-year term as the state's second-in-command.

Despite the obvious differences, one similarity between the allegations against Kavanaugh and Fairfax is timing. The allegations against Kavanaugh dated back nearly 30 years and those against Fairfax relate to encounters he had in the early 2000s. At this juncture in our history when survivors are now more than ever empowered—finally, rightfully—to come forward, the timing of their allegations necessitates an answer to an uncomfortable question: to what extent are the foundational concepts of due process followed when public persons are accused of sexual assault many years after the alleged conduct occurred?

A rudimentary principle that is almost universally accepted is that a party alleged to have done something (whether it be a crime, a tort, violation of some administrative regulation, etc.) is presumed not culpable (whether it is guilty, liable or otherwise responsible) unless proven otherwise. Reasonable minds can certainly differ on the precise contours of such procedural safeguards, but the question is whether they should be applied in this context. Kavanaugh and Fairfax are public figures and with that comes both moral and ethical responsibility.

When dealing with allegations of sexual assault, as human beings we tend to default toward feelings of sympathy and compassion for the survivors. Such emotion can and most often does lead to a bias toward victims that we mask through an assessment of credibility. In the case of Ford and Watson, both extremely accomplished and well-respected professionals, it's easy to demand that Kavanaugh be impeached and that Fairfax resign without giving either the benefit of (reasonable) doubt.

In a way, Kavanaugh benefited from the fact that the accusations were made against him in the backdrop of his confirmation hearing. The Senate Judiciary Committee was therefore able to use its extensive investigatory powers to conduct witness interviews and hear testimony from both Kavanaugh and Ford. The committee also ordered the FBI to conduct a supplemental investigation and issue a report on its findings. Sufficient or not, such procedural safeguards were largely determinative of Kavanaugh's eventual confirmation. In contrast, the allegations against Fairfax are not subject to any such formal vetting or oversight. Fairfax is, for all intents and purposes, left on his own with dwindling public support to defend against unsettling allegations he has steadfastly denied.

The #MeToo movement has revealed how unprepared, and perhaps how unwilling, we are to formulate a consistent approach to evaluating allegations of sexual assault against public figures that is fair to both sides. The fact is: both the accusers and the accused have an equal right to be heard, and we are not here to determine who should be ultimately believed. Rather, our message is the need to develop a framework where some foundational concepts of traditional due process should be followed—at least as a matter of principal, if not as a matter of legal strictures. By no means are we suggesting that public figures accused of these egregious acts are entitled to the procedural safeguards available in criminal proceedings, but basic principles of due process, such as allocating the burden of proof on the accuser, should apply. On the other hand, while our system dictates that we are all “innocent until proven guilty,” that does not mean that the presumed innocence of those accused in this context should remain in perpetuity.

The YL Editorial Board members: Leigh Ann Benson, Rachel Dichter, Rigel Farr, Scott Finger, Sarah Goodman, Thomas Gushue, Kevin Harden, Jae Kim, Kandis Kovalsky, Bethany Nikitenko, Rob Stanko, chairman; Jeffrey Stanton, Shohin Vance and Meredith Wooters

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pa. Federal District Courts Reach Full Complement Following Latest Confirmation

The Defense Bar Is Feeling the Strain: Busy Med Mal Trial Schedules Might Be Phila.'s 'New Normal'

7 minute read

Federal Judge Allows Elderly Woman's Consumer Protection Suit to Proceed Against Citizens Bank

5 minute read

Judge Leaves Statute of Limitations Question in Injury Crash Suit for a Jury

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250