Can Bystanders Make Failure-to-Warn Claims in Toxic Tort Cases?

A failure-to-warn claim is a staple of products liability litigation. The basic premise is that a manufacturer or seller failed to warn a consumer about an unreasonable risk of foreseeable harm associated with the use of a product.

February 25, 2019 at 03:00 PM

7 minute read

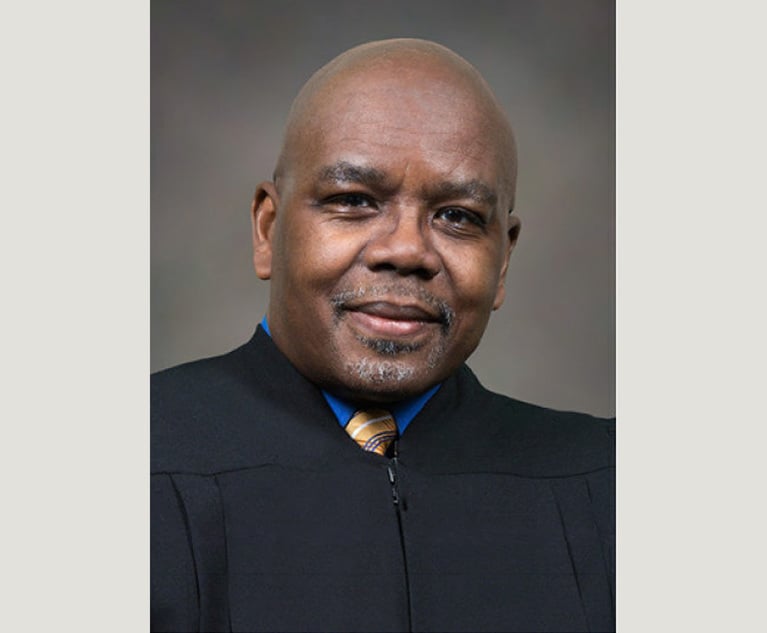

Stephen D. Daly, Manko Gold Katcher & Fox

Stephen D. Daly, Manko Gold Katcher & Fox

A failure-to-warn claim is a staple of products liability litigation. The basic premise is that a manufacturer or seller failed to warn a consumer about an unreasonable risk of foreseeable harm associated with the use of a product.

Plaintiffs pursuing toxic tort cases have begun to rely on failure-to-warn claims outside the strict consumer/seller context. Specifically, several personal injury lawsuits relating to the emerging contaminant per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have relied on failure-to-warn theories against manufacturers of PFAS. These lawsuits are distinct from many failure-to-warn cases in that the plaintiff is rarely a user or purchaser of the PFAS-containing product. Rather, the plaintiff is a mere bystander who, because of the conduct of the user of the product (the one the manufacturer allegedly failed to warn), was exposed to PFAS chemicals.

Federal courts dealing with these claims have had to address whether the manufacturers owe a duty to residents who did not purchase the PFAS-containing product but who live near where it was used.

Strict Liability or Negligence Theory

Failure-to-warn claims may be brought under either strict products liability or negligence theories, although the distinction between the two theories is murky. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in the context of addressing product design defects, has instructed that the theory of strict products liability “overlaps in effect” with the theory of negligence, although the court has tried to maintain a distinction between the two theories, see Tincher v. Omega Flex, 104 A.3d 328, 401 (Pa. 2014).

In Pennsylvania, under strict products liability, a plaintiff must show that the defendant's product was defective, the defect caused the plaintiff's injury and the defect existed at the time the product left the defendant's control, as in Wright v. Ryobi Technologies, 175 F. Supp. 3d 439, 449 (E.D. Pa. 2016). In a strict liability failure-to-warn case, the plaintiff establishes that a product is “defective” by showing that the defendant's warning of a “particular danger was either inadequate or altogether lacking,” thereby making the product unreasonably dangerous. For a negligent failure-to-warn claim, a plaintiff must establish that: the defendant owed a duty to provide an adequate warning of a dangerous aspect of its product; the defendant breached that duty by either failing to warn or providing an inadequate warning; the absence or inadequacy of the warning was the proximate cause of the plaintiff's injury; and damages.

In either case, a failure-to-warn claim turns on the reasonableness of a manufacturer's conduct in framing its warnings. Whether strict liability or negligence, “inevitably the conduct of the defendant in a failure to warn case becomes the issue,” see Olsen v. Prosoco, 522 N.W.2d 284, 289 (Iowa 1994). Several commentators have therefore concluded that “the strict liability action for failure to warn is substantially identical to its negligence-based counterpart.” See, e.g., Kenneth M. Willner, “Failures to Warn and the Sophisticated User Defense,” 74 Va. L. Rev. 579, 582-83 (1988).

'Menkes v. 3M'

PFAS compounds encompass a class of chemicals that have been used in hundreds of industrial processes and consumer products because of their resistance to heat, water and oil. Toxicity studies have identified links between PFAS chemicals and negative human health outcomes, but there remains uncertainty over how much PFAS exposure is safe for humans. The federal government has not yet set enforceable regulatory standards for PFAS, yet the number of PFAS-related lawsuits has exploded. Most of these lawsuits rely on traditional tort theories of liability, often including failure to warn.

One of these lawsuits, Menkes v. 3M, No. 17-0573 (E.D. Pa.), involves a lawsuit against the manufacturers of a fire-fighting foam that contained certain PFAS chemicals. The plaintiffs, a married couple that lives in Warminster, Pennsylvania, claim to have suffered various injuries as a result of the presence of PFAS in Warminster's public water supply. They claim that the manufacturers sold PFAS-containing fire-fighting foam to the U.S. Navy for use at two bases located in and near Warminster. The fire-fighting foam was used by the Navy to suppress fires on the ground and in aircraft hangars, which the plaintiffs allege caused PFAS chemicals to contaminate the soil and groundwater. The plaintiffs allege that the drinking water in the area surrounding the bases has been contaminated by PFAS chemicals.

The plaintiffs allege several causes of action against the manufacturers, including claims for failure to warn under both strict liability and negligence theories. Specifically, the plaintiffs allege that the manufacturers failed to warn the Navy, the users of the fire-fighting foam, about its harmful effects on human health and the environment. They claim that the failure to warn the Navy caused the plaintiffs to suffer their injuries. The manufacturers moved to dismiss both failure-to-warn claims.

Despite the similarities in the strict liability and negligent failure-to-warn theories, the court dismissed the strict liability claim but not the negligence claim. As to strict products liability, the court dismissed the claim because the plaintiffs were not the users or consumers of the fire-fighting foam. The court relied on Pennsylvania case law that supported the view that only “ultimate users or consumers” could recover for strict products liability. The court acknowledged that some Pennsylvania courts had allowed bystanders to pursue strict products liability claims, but the court distinguished these cases on the basis that all of them involved bystanders that were in “direct proximity” to the defective product. In contrast, the plaintiffs, residents in the general vicinity of the Navy's bases, were never present at the bases where the fire-fighting foam was used.

The court did not apply the same analysis in evaluating the plaintiffs' negligent failure-to-warn claim. The court acknowledged that “manufacturers already owe a duty to the consumers and users of their products to use reasonable care in manufacturing their products,” yet it used this legal premise not to dismiss the plaintiffs' claim (as it had for strict products liability) but to support it. The court held that in the negligence context, a manufacturers' duty extended to “nonconsumers or users living near facilities where a manufacturer's products are used” because it was foreseeable that “toxic chemicals used at a particular facility will not necessarily remain confined to that facility.”

Other Cases

Shortly after Menkes was decided, another federal court held that two manufacturers owed a duty to warn the purchasers of their PFAS-containing products in order to protect “people living near facilities operated by those purchasers and users.” See Wickenden v. Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics,1:17-CV-1056 (N.D.N.Y. June 21, 2018).

Yet the case law in this area continues to develop, and it has not been uniform. In yet another toxic tort case, one relating to a warehouse fire, a federal court in West Virginia dismissed a failure-to-warn claim against a manufacturer that was brought by neighboring residents that had not purchased or used the product at issue. See Callihan v. Surnaik Holdings of West Virginia, No. 2:17-cv-04386, (S.D. W.Va. Dec. 3, 2018). There, the defendants had sold allegedly hazardous materials to a warehouse that later caught fire, exposing the plaintiffs, neighboring residents, to allegedly harmful fallout. The court dismissed the plaintiffs' failure-to-warn claim against the sellers because the court held that the sellers owed a duty only to persons “who might be expected to use [their product].” The neighboring residents were not reasonably foreseeable users of the allegedly hazardous materials and they could not bring a claim on behalf of another party without a special relationship.

It will be interesting to monitor whether courts will follow the approach in Menkes or Callihan moving forward.

Stephen D. Daly is an attorney with the environmental, energy and land use law and litigation firm of Manko, Gold, Katcher & Fox, located just outside of Philadelphia. He can be reached at 484-430-2338 or [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Plaintiffs Seek Redo of First Trial Over Medical Device Plant's Emissions

4 minute read

'Serious Misconduct' From Monsanto Lawyer Prompts Mistrial in Chicago Roundup Case

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Bass Berry & Sims Relocates to Nashville Office Designed to Encourage Collaboration, Inclusion

- 2Legaltech Rundown: McDermott Will & Emery Invests $10 million in The LegalTech Fund, LexisNexis Releases Conversational Search for Nexis+ AI, and More

- 3The TikTokification of the Courtroom

- 4New Jersey’s Arbitration Appeal Deadline—A Call for Clarity

- 5Law Firms Look to Gen Z for AI Skills, as 'Data Becomes the Oil of Legal'

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250