Pa. Justices Express Wariness of 'Junk Science' in Applying Fair Share Act

An attorney told the Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Wednesday that applying the full weight of the Fair Share Act required juries to apportion damages in all products liability cases, but several justices said they were worried doing so would open the door to "speculation" and "junk science" in the courtroom.

March 06, 2019 at 02:07 PM

4 minute read

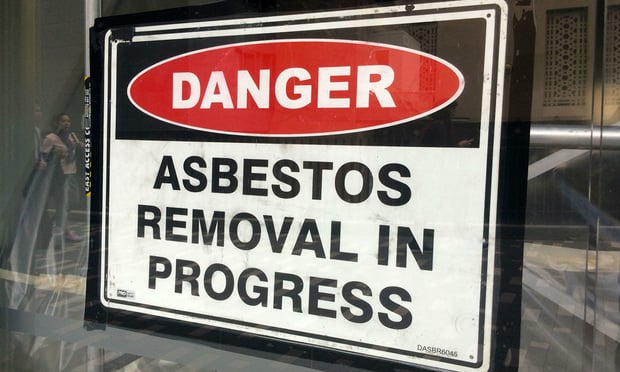

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

An attorney told the Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Wednesday that applying the full weight of the Fair Share Act required juries to apportion damages in all products liability cases, but several justices said they were worried doing so would open the door to “speculation” and “junk science” in the courtroom.

A full complement of the court heard arguments Wednesday in the asbestos case Roverano v. John Crane, a closely watched case that is expected to provide guidance to courts and litigators on how to apply the Fair Share Act in strict liability cases. Much of the argument session focused on whether damages should be apportioned equally to all defendants or whether juries should determine damages based on each defendant's conduct.

Duane Morris attorney Robert Byer, who represented the defendant Brand Insulations, told the justices that the language and intent of Act 17 of 2011, often referred to as the Fair Share Act, makes it clear that juries must assess damages against each defendant in all products liability cases.

“The bottom line is, this is what the General Assembly directed the courts to do,” Byer said.

Byer contended that juries could use evidence that typically comes in during the liability phase to establish that the asbestos exposure was regular, frequent and proximate when they assess what amount of damages each defendant should be saddled with.

Justices Max Baer and David Wecht said they did not think science could provide the level of detail that would be needed to properly determine how much each defendant contributed to the harm.

“Respectfully, your theory is interjecting junk science,” Baer said. “We've never held that duration of contact corresponds with culpability.”

Justice Christine Donohue offered similar sentiments.

“The jury could just speculate,” Donohue said. “You're just asking the jury to make it up.”

Justice Sallie Mundy also said she felt that using the evidence to allocate damages essentially altered the framework of the products liability cause of action, and Wecht, repeatedly referring to what he called “indivisible harm” that occurs in asbestos cases, said the problem may have arisen when the General Assembly ”cramm[ed]” strict liability issues into legislation pertaining to negligence principals.

“ There needs to be a fault determination,” Wecht said.

Byer, however, countered that the jury would not be tasked with apportioning liability percentages, but instead would just be assessing damages. Any arguments about the fairness or concerns about any one particular class of parties should be brought to the legislature, he said. He also noted other jurisdictions, such as Ohio, handle products liability cases in a similar manner, and said he was only asking courts to “apply the statute.”

The case stems from the lawsuit William Roverano, a former PECO Energy employee, and his wife brought against numerous defendants over claims he was exposed to asbestos-containing products that eventually caused him to develop lung cancer. In 2016, a Philadelphia jury awarded Roverano $6.3 million.

The verdict sheet listed eight defendants, but the jury did not determine how much each should contribute to the award. Instead the judge distributed the damages evenly between the defendants on a per capita basis. In December, a three-judge Superior Court panel vacated the trial court's ruling that the Fair Share Act did not apply, and remanded the case for a new trial to apportion liability.

Before the enactment of the Fair Share Act, a defendant found liable for any percentage of an incident could be made to pay the entire award. The act changed the law so defendants are only responsible to pay for the percentage they're found liable, and can only be made to pay the full award if they are found more than 60 percent responsible.

Edward Nass of Nass Cancelliere, who argued for Roverano, contended that the Supreme Court did not have to apply its ruling to all products liability causes of action, and could instead limit it to asbestos cases.

Nass further told the justices that the number of products a plaintiff can be exposed to, which could be as many as 40, the length of time between when the exposures happen and the diseases manifest, and the fact that science is unable to pinpoint which product caused the disease all make it extremely difficult for jurors to apportion damages. And, he argued, since none of the defendants warned about the damages of asbestos, the defendants all should be equally responsible for the damages.

“A percentage apportionment of liability in an asbestos action is nearly impossible, if not impossible,” he said. “If the medical community can't allocate who's responsible, how is a jury supposed to?”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Troutman Pepper Says Ex-Associate Who Alleged Racial Discrimination Lost Job Because of Failure to Improve

6 minute read

Over 700 Residents Near 2023 Derailment Sue Norfolk for More Damages

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Blank Rome Adds Life Sciences Trio From Reed Smith

- 2Divided State Supreme Court Clears the Way for Child Sexual Abuse Cases Against Church, Schools

- 3From Hospital Bed to Legal Insights: Lessons in Life, Law, and Lawyering

- 4‘Diminishing Returns’: Is the Superstar Supreme Court Lawyer Overvalued?

- 5LinkedIn Accused of Sharing LinkedIn Learning Video Data With Meta

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250