DA Krasner to Implement New Policies Aimed at Reducing Parole, Probation Times

On Thursday, Krasner's office announced new guidelines that Philadelphia prosecutors have been instructed to use when negotiating plea deals.

March 21, 2019 at 10:22 AM

5 minute read

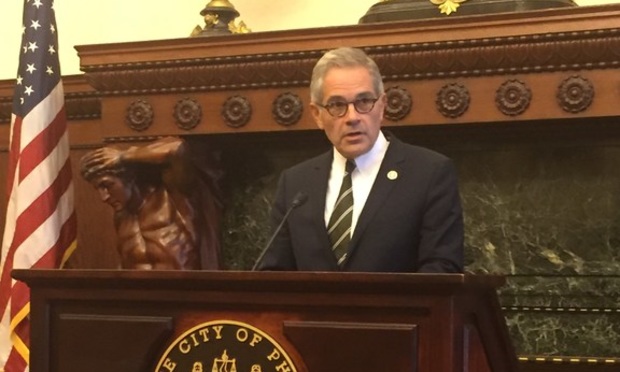

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner. (Photo: P.J. D'Annunzio/ALM)

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner. (Photo: P.J. D'Annunzio/ALM)

In a move seen as likely to shake up plea negotiations in Philadelphia, District Attorney Larry Krasner has announced new policies aimed at reducing the time defendants spend being supervised on parole and probation.

On Thursday, Krasner's office announced new guidelines that Philadelphia prosecutors have been instructed to use when negotiating plea deals.

The guidelines, which build on and somewhat modify initiatives announced last winter, generally advise prosecutors not to seek more than three years of probation for felonies, and to have 18 months as the average amount of time prosecutors recommend for total supervision, which includes time spent on both probation and parole. Regarding misdemeanors, prosecutors are now expected not to recommend supervision beyond one year, and to have six months be the average recommendation for supervision.

Prosecutors, according to the guidelines, will be able to go beyond the recommended ceilings, but will need to obtain prior approval from the office.

In an interview Wednesday, Krasner said academic studies and research conducted by his office indicates that supervision under probation or parole becomes increasingly less effective after about 13 months, and after three years, it begins to become more of a “series of trip wires” for defendants, rather than something that helps to rehabilitate defendants.

“What happens afterwards is that supervision actually makes things worse. It is not merely ineffective. It causes people to fail. It causes them to fail in ways that puts them back in jail. It arguably causes crime. It doesn't fail to stop it, it causes crime,” Krasner said, giving the example of defendants who may have bosses who refuse to allow them to report.

One wrinkle that may effect how widespread the policy can be implemented is state requiring that the maximum of a sentence be at least twice as long as the minimum, which often times ensures lengthy time spent on supervision because, even when inmates are released early, they must spend the remainder of their sentences under supervision. Krasner said the recommendations from prosecutors will continue to follow state law, but prosecutors will be advised to seek the reduced supervision times when applicable.

According to Krasner, supervision is often used as a bargaining chip, or a means to effectuate a back-and-forth between prosecutors and defense attorneys, where prosecutors agree to lesser prison sentences in exchange for more time on supervision. Curbing those tendencies, he said, are partly what the new guidelines are aimed at.

“That's really more about human psychology than anything that's sound policy, so part of this is meant to address that,” he said. “Lawyers, especially the type of lawyers who do trials, are competitive people, and we should be doing what's in the best interest of Philadelphians not what is psychologically attractive when you're negotiating a case.”

Another factor that is likely to affect how the policy is implemented is how the Philadelphia judiciary will react.

After the office announced a series of new policies last year, including asking judges to consider the cost of incarceration to tax payers and not seek cash bail for 25 criminal charges, such as criminal mischief, prostitution and retail theft, the office received some pushback from judges.

Krasner said that, while he expects the “vast majority” will be accepted, he is anticipating that some of the deals negotiated under these new guidelines will be rejected. However, he said the office is sensitive to the input from judges and prosecutors will be trained on the underlying policy goals, which could be used to help persuade some members of the judiciary.

“I know the courts have an interest in criminological science,” he said. “We would be prepared to talk about them. The judiciary would be very interested in the science and reasoning behind these policies.”

With more than 40,000 people on probation in Philadelphia and 269,000 across the state, Pennsylvania has the second-highest supervision rate in the country, according to a report by the Prison Policy Initiative, and in places like New York City, which saw declines in supervision caseloads, the crime rate has similarly fallen, the study noted.

Krasner also noted that bipartisan members of the state General Assembly have been pushing legislation that has similar goals in mind regarding reducing the number of defendants under supervision.

When it comes to goals, Krasner said there was ”no magic number” in terms of how much he would like to see the supervision rates reduced, and that each case will be evaluated on an individual basis. But, he added, he would like to see significant reductions.

“Our rolls are absurd. It would be nice to cut this number in half and then have a conversation,” he said. “That to me seems a modest goal when all five boroughs in New York are at 12,700 and cutting this number in half would mean a much much smaller city still has far more than New York.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Morgan Lewis Shutters Shenzhen Office Less Than Two Years After Launch

Sanctioned Penn Law Professor Amy Wax Sues University, Alleging Discrimination

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1'A Death Sentence for TikTok'?: Litigators and Experts Weigh Impact of Potential Ban on Creators and Data Privacy

- 2Bribery Case Against Former Lt. Gov. Brian Benjamin Is Dropped

- 3‘Extremely Disturbing’: AI Firms Face Class Action by ‘Taskers’ Exposed to Traumatic Content

- 4State Appeals Court Revives BraunHagey Lawsuit Alleging $4.2M Unlawful Wire to China

- 5Invoking Trump, AG Bonta Reminds Lawyers of Duties to Noncitizens in Plea Dealing

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250