Products Liability Jury Test Shouldn't Include Phrase 'Unreasonably Dangerous'

As the Tincher court addressed the historical rationale for strict liability in product cases and grappled with the niceties and distinctions between tort principles of negligence and strict liability, the court embraced two legal tests jurors should be instructed to use in deciding whether a product is defective: the consumer expectation test (CET) and the risk utility test (RUT).

May 02, 2019 at 12:47 PM

6 minute read

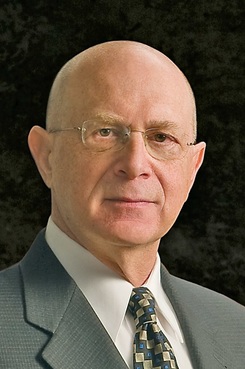

Larry Coben, Anapol Weiss

Larry Coben, Anapol Weiss

In 2014, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued an opinion in the case of Tincher v. Omega Flex, 628 Pa. 296. Since then, the legal community has been abuzz over the literal changes that decision made to products liability law, as well as claims for changes in other related aspects of our law. One of the most confounding issues that the Tincher court touched upon but (with due respect) without any thoughtful analysis, is the underlying defense notion that a jury needs to be instructed that a product is defective only if it is also “unreasonably dangerous.”

As the Tincher court addressed the historical rationale for strict liability in product cases and grappled with the niceties and distinctions between tort principles of negligence and strict liability, the court embraced two legal tests jurors should be instructed to use in deciding whether a product is defective: the consumer expectation test (CET) and the risk utility test (RUT). Stated simply, the court concluded that in determining if a product is unreasonably dangerous a jury must apply either the CET or the RUT. Therein lies the issue: if a jury is instructed and finds that a product is defective because it did not comport with the CET or the RUT, then what practical or legal purpose is obtained by instructing or permitting argument of counsel inserting the phrase unreasonably dangerous? In other words, because a finding of defect can only be obtained upon proof that the design/manufacture/warning violated the CET or RUT, what possible interest is served by inserting this phrase? Stated otherwise, does the Tincher decision excuse dangerous consumer products so long as the product is not unreasonably dangerous? We think not. And, we suggest that adding this phrase to standard jury instruction or allowing counsel to argue that a defect can only exist if the product is both defective and unreasonably dangerous adds a layer of proof that is both unwarranted and dangerously inconsistent with the CET and the RUT.

Let's begin this analysis with two succinct rulings in Tincher: “ … we hold that, in Pennsylvania, the cause of action in strict products liability requires proof, in the alternative, either of the ordinary consumer's expectations or of the risk-utility of a product.

“Essentially, given that a term like 'defective condition unreasonably dangerous' is not self-defining, courts have offered multiple definitions applicable in the several contexts in which a definitional issue has arisen, all effectuating the single policy that those who sell a product are held responsible for damages caused to a consumer by the reasonable use of the product.”

When the test applied is the consumer expectation, the question for the jury is whether the defect involves a “danger unknowable and unacceptable to the average or ordinary consumer.” It's not whether the product is unreasonably dangerous to the consumer. Likewise, when the RUT is applied, the test whether a reasonable person would find that “the probability and seriousness of harm caused by the product outweigh the burden or costs of taking precautions.” The RUT test does not ask the jury to decide if the product is unreasonably dangerous after finding that its risk of harm outweighs the burden of correcting the faulty design.

These two tests reflect Pennsylvania's continued adherence to the principle that, in a products liability action, the trier of fact must focus on the product, not on the manufacturer's conduct. Further, and perhaps more to the point, Section 402A of the Restatement of Torts 2d includes the singular comment that products liability obtains for the marketing of a product including a defective condition unreasonably dangerous, rather than that the product includes a defect and the defect is in an unreasonably dangerous condition. As explained in Comment i to Section 402A, “… what is meant by 'unreasonably dangerous' … is that the article sold must be dangerous to an extent beyond that which would be contemplated by the ordinary consumer who purchases it, with the ordinary knowledge common to the community …” In other words, the phrase unreasonably dangerous has no independent significance in gauging liability.

This unremarkable conclusion was drawn by the California Supreme Court years ago in Barker v. Lull Engineering, 573 P.2d 443, 450-451 (1978): the plaintiff need not prove that the manufacturer acted unreasonably or negligently in order to prevail in such an action.

To require an injured plaintiff to prove not only that the product contained a defect but also that such defect made the product unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer would place a considerably greater burden upon him than that articulated in … California's seminal products liability decision. … We are not persuaded to the contrary by the formulation of Section 402A which inserts the factor of an unreasonably dangerous condition into the equation of products liability.

“The restatement draftsmen adopted the unreasonably dangerous language primarily as a means of confining the application of strict tort liability to an article which is 'dangerous to an extent beyond that which would be contemplated by the ordinary consumer who purchases it, with the ordinary knowledge common to the community as to its characteristics' … .”

Critical to this analysis is that Pennsylvania's rejection of requiring proof that a product is both defective and unreasonably dangerous is the observation that the commonwealth's rejection of this added burden was announced by our Supreme Court in Berkebile v. Brantly Helicopter, 337 A. 2d 893 (1975) and not in Azzarello. The Berkebile court observed—sounding more like Tincher than Azzarello—that: “The salutary purpose of the 'unreasonably dangerous' qualification is to preclude the seller's liability where it cannot be said that the product is defective; this purpose can be met by requiring proof of a defect … The plaintiff must still prove that there was a defect in the product and that the defect caused his injury; but if he sustains this burden, he will have proved that as to him the product was unreasonably dangerous. It is therefore unnecessary and improper to charge the jury on 'reasonableness.'”

The Tincher court's opinion waxed and waned eloquently about a lot of legal principles, transitioning from a review of the parties' respective arguments to the evolution of negligence and strict liability principles in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, to the role of the court and juries in deciding questions of liability in products liability cases. In doing so, the actual holding in Tincher was limited to the adoption of the CET and RUT as the two tests which jurors must apply to determine whether a product is defective. This holding did not inform the bench or bar that jurors must be instructed that products liability depends not only on a violation of the CET or RUT but also upon a finding that the defect was unreasonably dangerous. Thus, this nebulous phrase should not be incorporated into jury instructions nor presented to jurors who will have a difficult enough time deciding liability using the newly adopted legal tests of defect.

Larry E. Coben, a shareholder at Anapol Weiss, handles products liability cases at the firm. Contact him at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pa. Federal District Courts Reach Full Complement Following Latest Confirmation

The Defense Bar Is Feeling the Strain: Busy Med Mal Trial Schedules Might Be Phila.'s 'New Normal'

7 minute read

Federal Judge Allows Elderly Woman's Consumer Protection Suit to Proceed Against Citizens Bank

5 minute read

Judge Leaves Statute of Limitations Question in Injury Crash Suit for a Jury

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Lawyers' Reenactment Footage Leads to $1.5M Settlement

- 2People in the News—Feb. 4, 2025—McGuireWoods, Barley Snyder

- 3Eighth Circuit Determines No Standing for Website User Concerned With Privacy Who Challenged Session-Replay Technology

- 4Superior Court Re-examines Death of a Party Pending a Divorce Action

- 5Chicago Law Requiring Women, Minority Ownership Stake in Casinos Is Unconstitutional, New Suit Claims

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250