Statute of Limitations That Could End 40% of Pa. Risperdal Cases Is Weighed by High Court

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Thursday probed into questions about what level of public awareness regarding the dangers of a widely used pharmaceutical can sufficiently put potential plaintiffs on notice to investigate their claims.

May 16, 2019 at 04:11 PM

4 minute read

Office of Janssen Pharmaceuticals, part of Johnson & Johnson, at the Leiden Bio Science Park in the Netherlands. Photo: Shutterstock

Office of Janssen Pharmaceuticals, part of Johnson & Johnson, at the Leiden Bio Science Park in the Netherlands. Photo: Shutterstock

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Thursday probed into questions about what level of public awareness regarding the dangers of a widely used pharmaceutical can sufficiently put potential plaintiffs on notice to investigate their claims.

According to an attorney representing two men alleging to have been injured by the antipsychotic drug Risperdal, the level of public awareness needs to reach as far as coverage in small-town newspapers.

Media coverage of drugs including Vioxx and Avandia reached that level of critical mass, Kline & Specter attorney Charles “Chip” Becker told the justices, but coverage of the link between Risperdal and the growth of excess breast tissue did not.

“The Vioxx story would have been covered by the Hazleton Standard Speaker,” Becker said. “There was scattered scientific literature and news coverage [regarding Risperdal]. … It's not in the same state, to say nothing of the same ball park.”

Dechert attorney Robert Heim, however, who argued on behalf of drugmaker Janssen, contended that, several years before their suits were filed, the alleged dangers of Risperdal had been covered in national nightly news segments by CBS and Fox, and attorney advertisement was also all over the internet.

“This is a case about no diligence. None. None whatsoever,” Heim said.

The arguments came in the cases Saksek v. Janssen and Winter v. Janssen as part of Janssen's effort to impose a strict cut-off date for when plaintiffs claiming to have been injured by the drug can bring claims. Plaintiffs, on the other hand, are seeking to have juries determine whether a plaintiff timely brought his claims, based on the particular facts in each case. Specifically in the two cases before the justices, the plaintiffs contend they were not made aware of their injuries until their mothers saw an attorney advertisement on TV about the dangers of the drug.

According to attorneys involved in the litigation, setting a strict deadline at two years after June 2009, which was the cut-off date initially imposed by the trial court, could bar about 40% of the 7,000-strong Risperdal mass tort program pending in Philadelphia. The state Superior Court has since moved the timeline back even farther, to 2006, which is the date that the Risperdal label was changed to note the link between Risperdal and the growth of excess breast tissue in the boys and young men who took the drug.

According to Becker, there was no way his clients could reasonably have been put on notice about the link between the drug and the tissue growth. He noted that in 2006, both plaintiffs were taking generic versions of the drug so they would not have known about the changes to the Risperdal label, which was aimed at informing doctors, rather than patients, and that the plaintiffs had been under the impression their breast growth was due to weight gain, rather than what Becker described as an endocrine disorder as a result of the drug.

Justice Debra Todd asked whether, instead of framing the issue as a discovery rule question, the courts could instead apply the test for summary judgment, and send the issue to a jury if there were any questions of fact.

Becker said that, in part because Pennsylvania's discovery rule is less forgiving than in other venues, courts have done exactly that.

“Yes. Wholeheartedly, yes,” he said.

But Becker stopped short of asking the court to say that all questions about a plaintiff's reasonable diligence should become a jury question, and added that, while some cases don't raise factual issues, “there happens to be one here.”

Heim, however, said, even despite all the news coverage and online attorney advertising, the two plaintiffs at issue had been aware they suffered injuries as early as 1998 and 2002. At that point the plaintiffs needed to do some form of investigation.

Chief Justice Thomas Saylor said Heim raised what appeared to be the critical issue in the dispute.

“If some gross abnormality manifests itself, you can say now you have some obligation to investigate that,” Saylor said.

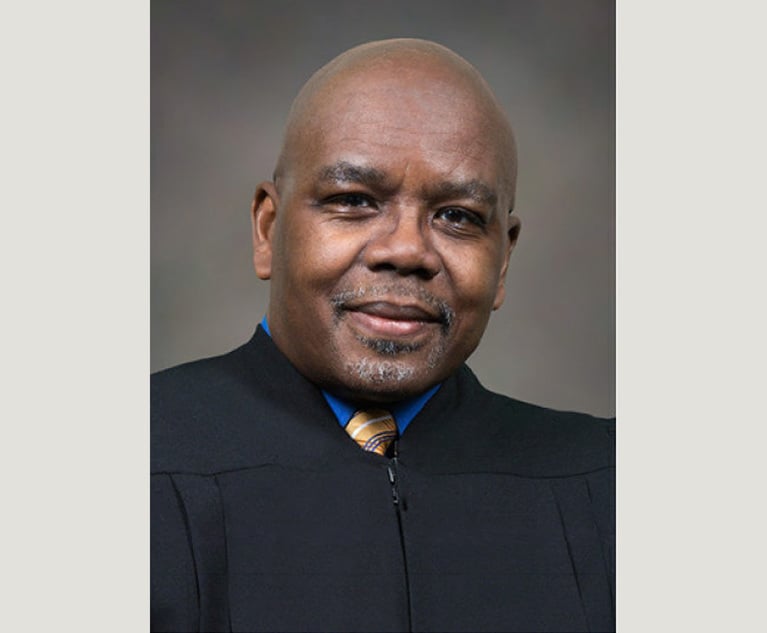

Justice David N. Wecht, however, noted that both the trial court and the Superior Court came to differing dates as to when the statute of limitations should apply.

“Is that a suggestion of the fact that reasonable minds could differ, and so it should go to the jury?” he asked.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Discordant Dots': Why Phila. Zantac Judge Rejected Bid for His Recusal

3 minute read

Pittsburgh Jury Tries to Award $22M Against J&J in Talc Case Despite Handing Up Defense Verdict

4 minute read

Plaintiffs Seek Redo of First Trial Over Medical Device Plant's Emissions

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1'A Death Sentence for TikTok'?: Litigators and Experts Weigh Impact of Potential Ban on Creators and Data Privacy

- 2Bribery Case Against Former Lt. Gov. Brian Benjamin Is Dropped

- 3‘Extremely Disturbing’: AI Firms Face Class Action by ‘Taskers’ Exposed to Traumatic Content

- 4State Appeals Court Revives BraunHagey Lawsuit Alleging $4.2M Unlawful Wire to China

- 5Invoking Trump, AG Bonta Reminds Lawyers of Duties to Noncitizens in Plea Dealing

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250