Moving Toward Cleaner Energy While Maintaining Our Legal Safeguards

Only one part of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's policy statement known as the Green New Deal actually deals with the environment. Most of the statement seeks to promote more jobs-oriented policies such as infrastructure renewal, building weatherization projects, and the promotion of so-called “Buy Clean” laws.

July 25, 2019 at 11:35 AM

9 minute read

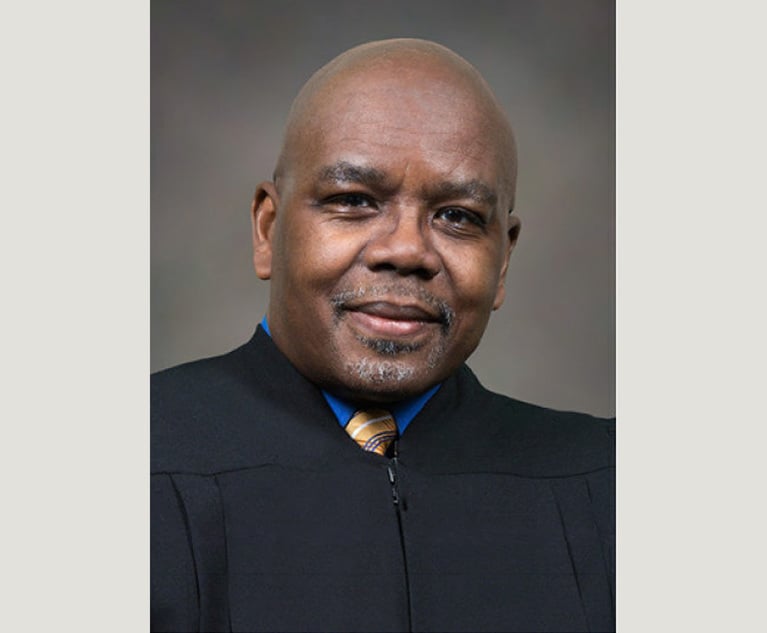

Daniel B. Markind of Flaster Greenberg.

Daniel B. Markind of Flaster Greenberg.Only one part of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's policy statement known as the Green New Deal actually deals with the environment. Most of the statement seeks to promote more jobs-oriented policies such as infrastructure renewal, building weatherization projects, and the promotion of so-called “Buy Clean” laws. To be fair, there are projected secondary environmental benefits to all of these things, too, but the major focus of the policy—the transition away from fossil fuels—has basically only one environmental benefit as its purpose. That benefit is, of course, the reduction of greenhouse gases in the environment and the hope for reversal of climate change.

That environmental component contains some questions that require us to think realistically, and not idealistically, of what we're really trying to accomplish. It also portends what the dangers are to our government and our system of justice should we fail to implement these policies in a thoughtful, sensible and careful manner.

The goal is clear. Both as a society and a world community, and in order to combat climate change, we wish to transition away from fossil fuels within a short period of time. Putting aside the question of whether this is feasible given the current state of technology and a host of economic and practical concerns—a topic which remains debatable—the legal methods we use to accomplish this will not only define how we govern ourselves in the 21st century, but will establish what rights and freedoms we most prize and value.

Unfortunately, there is no infrastructure currently in place to handle such a dramatic shift in energy sourcing. Constructing the infrastructure over a matter of years instead of decades will be a Herculean task. Ocasio-Cortez states that it will require a mobilization on the scale of World War II to accomplish this, which is perhaps, an understatement. Unfortunately, history shows that when such mobilization takes place, the biggest loser is often the environment itself. Ironically, in this case, that is what we are trying to save.

In order to carry out what the Green New Deal asks, we will need to attack on two fronts. First, we must make fossil fuels either illegal or economically infeasible. Second, we must make renewable sources far more readily available, storable and transmittable than at present. And we must do all of these things quickly, and in a coordinated manner.

If we want to make fossil fuels illegal, we will need a legal basis for doing so. Such bases do exist in other areas. For example, the Food and Drug Administration has the right under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act to ban medical devices for human use if it finds that the use of such a device would result in an unreasonable and substantial risk of illness or injury.

No such authority exists for fossil fuels, yet. However, enacting such a law would be fraught with peril. While not widely appreciated, fossil fuels contain the building blocks for nearly all the plastics and pharmaceuticals we use. Any public support for the Green New Deal would no doubt diminish as soon as the public realizes that banning the production of fossil fuels might also mean interfering with the production of drugs we use to fight cancer, control high blood pressure, prevent deaths from AIDS and otherwise keep our citizenry healthy. Therefore, before we even start trying to ban all fossil fuel production, we must realize this will not and cannot happen any time soon, and certainly not before we find suitable substitutes as the chemical building blocks for our modern pharmaceuticals. The best we can achieve is to reduce fossil fuel production substantially by making it unnecessary for providing our power, packaging and transportation needs.

The other method to reduce reliance on fossil fuels—that is, by creating economic infeasibility— would be to tax fossil fuel production to the point where its use would no longer be economical. However, again we face the same problem. How can we tax fossil fuel production to the point where its use for power and transportation is too high but not for the production of pharmaceuticals?

The obvious answer is that we tax the end-use product such as gasoline or heating oil. This raises a geopolitical question. If the rest of the world does not join us in our environmental efforts, the energy companies likely will seek to export their excess production. Should that happen, our ultimate goal will be diminished as fossil fuels will continue to be extracted and used in large quantities—yes, not in this country, but still other places around the globe where they will continue to do harm to the climate. It also raises a troubling question. Does the federal government even have the power to tax the production of a resource, limit its subsequent use only to those approved by the government, and then prohibit its export? If it does, then aside from being an extraordinary expansion of federal power, the precedent it sets could be quite dangerous.

Let us turn now to the issues relating to powering our future economy. In 2019, over 80% of our energy comes from fossil fuels. Again assuming that realistically we could switch to all renewables within 12 years, a highly debatable proposition, we would have to construct the power grid to do so. No such physical grid currently exists. In such a short time, we would have to conceptualize, design, permit and construct a nationwide renewable power grid.

To do that, we must limit time delays in implementation and prevent local disruption of national priorities. For example, time limits would need to be set and be very stringent when conducting National Environmental Policy Act reviews. Currently, from conception to completion it can take 20 years to construct an interstate highway. Much of that pertains to environmental reviews and local challenges about proposed routes. Obviously, full mobilization to effect a switch to all renewable energy within a decade cannot allow this. Deciding which challenges to allow, on what basis, and within what time frames will be crucial.

Who would decide this conceptually? And then what individuals would be empowered to make the final decisions? Before we can decide on this, we also need to determine if there even is a legal basis for doing so. Can the federal government, without a constitutional amendment, construct a system that in effect limits the ability of the judiciary to review executive branch administrative decisions? At the least, can it force the court system to collapse its time frames, again bringing the judiciary under certain controls of the executive branch?

Another necessity will be to clearly delineate federal priority. Currently, even after a federal agency—in this case the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission—approves an interstate oil and gas pipeline, state governors like New York's Andrew Cuomo can veto the project by refusing to grant it certain permits under Section 401 of the Federal Clean Water Act.

Such a state veto cannot be permitted in building the new renewable grid. However the process is structured, once the required permits have been granted at the federal level, they cannot be held up at the state or local level. This will not be good news for local zoning laws—or for those opposed to having aspects of the new grid located nearby under the so-called “NIMBY” doctrine. Therefore, to accomplish our goal, all local zoning and land use laws that disrupt the creation of the new power system will need to be subordinated to federal decisions.

Of course, this entire system puts enormous power in the hands of certain federal officials. The history of our country has been marked by a distrust of such power. In fact, much of our system of government is structured to prevent exactly that.

Should we decide to grant such enormous power to a select few, it will be wise to start promptly deciding who would choose the people that are to be granted such power, as well as on what basis and under what constraints. Certainly, this will be enormously contentious. We also need to determine what kind of safeguards we can establish against those who might use their positions for personal gain.

These are only a few of the issues that must be decided if we are serious about converting to a “renewable” economy in a truncated time frame. There are innumerable others, including limiting the notion of public bidding on many contracts—it will simply take too much time. While we argue back and forth about “Going Green,” it would be more beneficial to think through how we would do it, and on what legal and constitutional authority could we cut the many corners that need to be cut in order to make all of this happen in so short of a period of time.

Remember, the goal is an economy newly structured in a way to help preserve the planet. While politicians and activists seek to reduce this to base slogans, it will be enormously complicated to even determine the legal basis and parameters under which this can occur. That does not mean it should not be tried. To the contrary, it means that it is essential we think about these issues now and work our way through them. It would be the epitome of folly were we to cause total upheaval to our system of government and separation of powers yet find out at the end that we have caused more damage to the planet than we would have had we just stood still.

Daniel Markind is a shareholder at Flaster Greenberg and resides in its Philadelphia office. He can be reached at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Plaintiffs Seek Redo of First Trial Over Medical Device Plant's Emissions

4 minute read

'Serious Misconduct' From Monsanto Lawyer Prompts Mistrial in Chicago Roundup Case

3 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250