Creative Solar Development Could Help Once-Contaminated Lands Shine Again

While solar markets in many other states have flourished, Pennsylvania has been left largely in the shade, with less than 1% of the commonwealth's electricity generated by solar.

July 26, 2019 at 11:07 AM

9 minute read

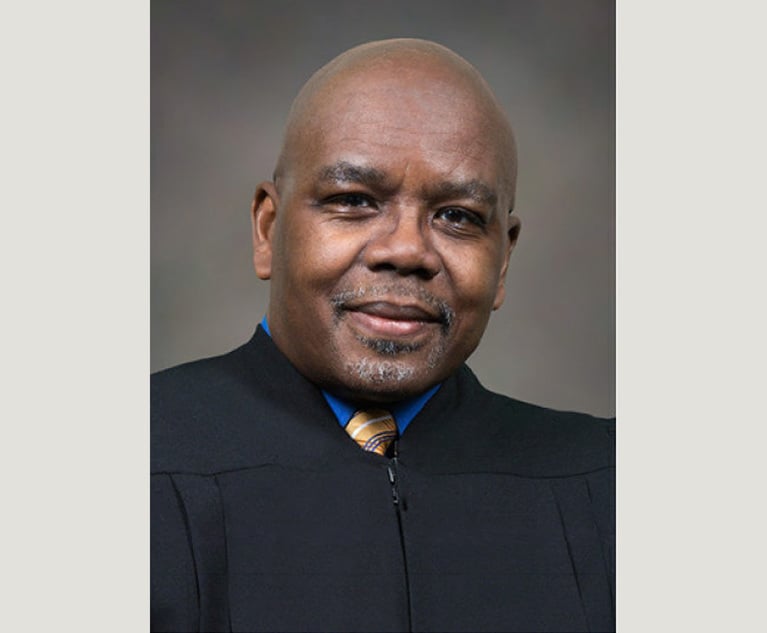

(Left to right) Karen Davis and Dan Reiter Fox Rothschild (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

(Left to right) Karen Davis and Dan Reiter Fox Rothschild (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

Solar energy is here to stay, efficiently and reliably harnessing the sun's energy to provide a clean, renewable source of electricity that can help power our homes and businesses. For many Pennsylvanians interested in going solar, however—whether purchasing their own system for on-site usage; hosting a third-party-owned system and purchasing the solar power through a long-term power purchase agreement; subscribing to a community solar garden; or leasing out their land to host a large-scale solar system that feeds its electrical output into the energy grid—the past decade has been somewhat frustrating. While solar markets in many other states have flourished, Pennsylvania has been left largely in the shade, with less than 1% of the commonwealth's electricity generated by solar.

This has not gone unnoticed. In 2018, after more than a year of intense and ongoing focus and expert collaboration on this issue that continues today, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, Energy Programs Office, released “Pennsylvania's Solar Future,” an effort to identify and explore strategies to achieve an aggressive but realistic goal—generating 10% of Pennsylvania's electricity from in-state solar by 2030. Given the current trajectory of Pennsylvania's solar market, only half of 1% of Pennsylvania's electricity would come from solar by 2021, and the commonwealth would likely fall far short of its 2030 goal.

“Pennsylvania's Solar Future” reaches a number of conclusions that reflect successes in other states. The report asserts that Pennsylvania will need to add approximately 11 gigawatts of new solar capacity from all sources to reach its 2030 goal—the equivalent of five massive coal or nuclear power plants. It maintains that financial incentives, access to capital and a clear legal and regulatory framework can help drive this growth; and that locating suitable sites, and ensuring that an efficient and reliable path exists to obtain the necessary approvals for, and actually interconnect, the new solar systems will be critical.

This last ingredient is key. To build more solar, you need a place to put it. Setting aside very valid debates over land use, zoning, conservation and many related concerns, the law of supply and demand will play a significant role. Land in Pennsylvania is often expensive, particularly in proximity to major metropolitan areas, where it can cost tens of thousands of dollars per acre, translating into significant ground lease rents.

For the largest, utility-scale solar systems, developers will seek out remote areas of the commonwealth with large, affordable tracts of land where construction and development may be more streamlined, and relatively low population density does not pose significant obstacles. Community solar gardens, on the other hand—which have flourished in many other states and are likely coming to Pennsylvania as contemplated in pending legislation—require customers to be within a certain distance of the system. Even for systems designed for on-site usage, significant parcels of developable suburban land at workable prices are likely to be elusive. This presents an opportunity to expand Pennsylvania's solar energy resources while simultaneously promoting the clean and productive use of environmentally challenged sites … solar energy redevelopment of brownfields.

Brownfields—properties for which redevelopment is complicated by the presence or potential presence of contamination—offer a plentiful supply of affordable land in desirable locations for development of renewable energy projects. There are an estimated 450,000-plus brownfields in the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, many of which have attributes necessary for successful renewable energy projects. They are often located in heavily populated areas, have access to the grid and are priced affordably. Both the EPA and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP) encourage reuse of brownfields for renewable energy projects. Brownfield owners can receive payments from the energy developer to defray cleanup costs, while the public benefits from the preservation of greenspace and redevelopment of brownfields. However, use of a brownfield for a renewable energy project has challenges related to relief from cleanup liabilities, conflicting interests between the property owner and developer, the need to assuage lender concerns and increased complexity of project construction and operation.

A developer may find relief from liability at EPA-led brownfields as a bona fide prospective purchaser (BFPP), now available directly to lessees under the Brownfields Utilization, Investment, and Local Development (BUILD) Act of 2018, subject to certain conditions. To qualify for and maintain BFPP status, a developer must: demonstrate that it is not a potentially responsible party (PRP); conduct all appropriate inquiries as defined by EPA regulations (AAI); take reasonable steps to prevent a release of hazardous substances; provide cooperation, assistance and access to the EPA; not impede the cleanup; and comply with applicable land use restrictions, among other requirements. If a developer meets these criteria, it should not be liable as an owner/operator for response costs. The EPA's recourse is limited to a “windfall lien” if an EPA response action increases the property's fair market value. A detailed discussion of AAI is beyond the scope of this article, but one key requirement is a recent (no more than 180 days old) Phase I Environmental Site Assessment that complies with applicable ASTM and EPA standards. Pennsylvania's Act 2 program provides a release from state liability for owners or developers of sites remediated according to the Act's standards and procedures. An April 21, 2004 One Cleanup Program Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between PADEP and EPA Region 3 clarifies the role of the EPA in sites remediated under Act 2.

Both energy developer and property owner have an interest in maintaining control over the property and protecting their investments. Property owners will not want a renewable energy project to impair or interfere with their remediation and trigger any re-openers by the agency, and may be concerned about the impact of construction, operation and maintenance of a renewable energy project. The energy developer will want and need a long-term commitment from the owner that protects its investment in the infrastructure and equipment installed at the property, including ensuring the solar system is able to operate without issue over several decades. These tensions need to be addressed in an agreement between the energy developer and property owner, often at the time of land acquisition by the energy developer, or in a long-term ground lease.

A successful renewable energy project also requires making the energy developer's lenders and equity investors, and the property owner's mortgage lenders, comfortable with the environmental condition of the property and associated risk allocations. Superfund contains a secured creditor exemption for lenders who hold indicia of ownership to protect a security interest, do not participate in the management of the contaminated site and do not cause or contribute to a release of hazardous substances, according to federal law at 42 U.S.C. Section 9601 (20). The secured creditor may foreclose on the property without incurring Superfund liability so long as the lender seeks to sell, re-lease or otherwise divest the property at the earliest practicable, commercially reasonable time, on commercially reasonable terms, taking into account market conditions and legal and regulatory requirements. Pennsylvania Act 3 provides similar relief from cleanup liability for commercial lending if the lender does not cause or exacerbate the contamination. However, for energy developers, renewable energy project financing is often secured by, among other collateral, the project itself (i.e., personal property under the Uniform Commercial Code) and by pledges of equity interests in the project companies (also governed by the UCC), rather than real property. Lenders and investors on the project side need to be comfortable that they may foreclose and take necessary actions to protect their investment, without incurring cleanup or other environmental liability.

Many brownfields are subject to environmental covenants that impose use and activity restrictions. Areas that have been capped may be subject to limitations regarding the use of heavy equipment or vehicles, for example. Excavation or penetration of the cap may be prohibited. Ballasted ground mount solar array systems are available, but the design, installation, operation, maintenance and decommissioning of such systems may be more complicated and costly than conventional systems. Allowing a property owner/operator access to operate and maintain the environmental remedy may also pose challenges to the energy developer. These and other issues may complicate the renewable energy development of brownfields, but should not be insurmountable and may even be offset by the decreased land costs of a brownfield-sited solar project.

The future of solar energy in Pennsylvania appears bright. One benefit of being late to the party may be the opportunity to learn from other states' successes and challenges. As stakeholders continue to collaborate on making measurable progress for solar in Pennsylvania, and as necessary legislation, rules and regulations are implemented, using some of the commonwealth's environmentally challenged lands for solar and other renewable energy generation should remain an important piece of the puzzle. “Pennsylvania's Solar Future” smartly identified the potential for a win-win in this area. While brownfields redevelopment can be intimidating, with risk can come reward for us all.

Dan Reiter is a partner in the Exton office of Fox Rothschild and a co-chair of the firm's energy and natural resources practice group. He can be contacted via email at [email protected] and by calling 215-299-3825.

Karen H. Davis is a partner in the Exton office of the firm and a member of the firm's environmental department. She can be contacted via email at [email protected] and by calling 610-458-6702.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Plaintiffs Seek Redo of First Trial Over Medical Device Plant's Emissions

4 minute read

'Serious Misconduct' From Monsanto Lawyer Prompts Mistrial in Chicago Roundup Case

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1We the People?

- 2New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 3No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 4Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 5Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250