The King's Bench, the Death Penalty and the Matter of Race

Pennsylvania race was and remains a thumb on the capital case scales—in the decision of who faces the death penalty; in the selection of jurors and in jurors' ultimate decision of whether to vote for death.

September 10, 2019 at 10:46 AM

4 minute read

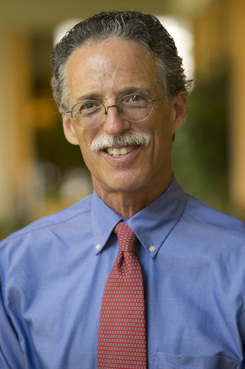

Jules Epstein

Jules Epstein

On Sept. 11, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court will hear argument in two cases raising a challenge to the death penalty process in this commonwealth as so dysfunctional as to violate the Pennsylvania Constitution. In doing so, it will decide first whether to exercise its King's Bench authority and hear the substantive claims; and if so whether the system is indeed so broken that it requires action by the court. Whatever it decides, it must confront the indisputable fact that in Pennsylvania race was and remains a thumb on the capital case scales—in the decision of who faces the death penalty; in the selection of jurors and in jurors' ultimate decision of whether to vote for death.

That conclusion was one of several submitted to the court in the pleadings of the two petitioners, and was emphasized in an amicus brief co-authored by this writer and submitted on behalf of concerned academics and social scientists. But the findings supporting this are neither abstract nor theoretical—and regarding race directly impacting who gets sentenced to death those findings come directly from the report commissioned by Pennsylvania's legislature.

After years of study, the Joint State Government Commission issued a report in June 2018 titled "Capital Punishment in Pennsylvania." Submitted to the legislature, the report details an abundance of deficiencies in the capital punishment process in Pennsylvania. These included, but were not limited to, problems of geographic disparity in capital punishment within Pennsylvania; inadequate funding for defense counsel; counsel who were too-often under-resourced or ill-suited to the task of capital case representation; and problems of disparate treatment due to race.

At its simplest, the data conclusively show the following—white victim cases result in the imposition of a sentence of death at over twice the rate where the victim is black. The data are compelling. The report shows based on the court system's own data that death sentences returned at penalty trials were at 45% (31 in 69) in cases with white victims and 20% (15 in 74) in cases with black victims.

Were this the only area in the capital case process where race played a role, it would be enough to warrant the intervention of the court. But other data show that race is also a factor in prosecutorial decision-making on whether to classify a case as capital-eligible; and the disparate use of peremptory challenges to exclude black citizens from jury service in capital cases is shown to have a long and ignoble history in Pennsylvania.

The brief amici curiae showed that researchers have found similar racial effects in the capital process in other states, again at the charging, juror selection and sentencing stages. The importance of this is clear—it confirms that the Pennsylvania findings are not anomalies or inaccurately depicting the capital case landscape.

Concerns that race has infected the capital case scheme are not new—they can be traced back at least to 1932. See Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 50 (1932) (noting that one of the claims raised was that "they were tried before juries from which qualified members of their own race were systematically excluded"); see Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) (reversing the second conviction and death sentence of one of the Powell v. Alabama defendants because blacks were systematically excluded from his jury venire). The U.S. Supreme Court confronted this head-on in 1978 when a claim of racial disparity was presented. In McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 292 (1978) the court, 5-4, concluded the proof was not yet there.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court faces that same question now, with the advantage of 41 years of additional research. While much progress has been made in this nation, the sad truth is that race reminds a decider in many arenas and a decisive factor in that most critical of determinations—who will live and who will die.

This racial influence compromises fairness, creates arbitrariness and undermines confidence in the criminal justice system. The consistency and power of these findings raise the fundamental question of whether the death penalty is imposed arbitrarily, i.e., without the "reasonable consistency" required by the Constitution's commands. When deciding whether and how to exercise its King's Bench power, the matter of race must be front and center.

Jules Epstein is professor of law and director of advocacy programs at Temple University Beasley School of Law. He co-authored one of the amici briefs in the pending King's Bench case.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Smaller Firms in 'Growth Mode' as Competition, Rates Heat Up

Trending Stories

- 1M&A Transactions and AB 1824: Navigating New Privacy Compliance Challenges

- 2Devin Nunes, Former California GOP Congressman, Loses Move to Revive Defamation Suit

- 3Judge Sides With Retail Display Company in Patent Dispute Against Campbell Soup, Grocery Stores

- 4Is It Time for Large UK Law Firms to Begin Taking Private Equity Investment?

- 5Federal Judge Pauses Trump Funding Freeze as Democratic AGs Launch Defensive Measure

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250