Ex-ADAs May Have Uphill Claim Against Phila. DA, but Likely to Force Explanation of Personnel Actions, Lawyers Say

Both lawsuits reference public statements Krasner made both before and after taking office in which he allegedly indicated favoring younger prosecutors.

September 25, 2019 at 05:05 PM

7 minute read

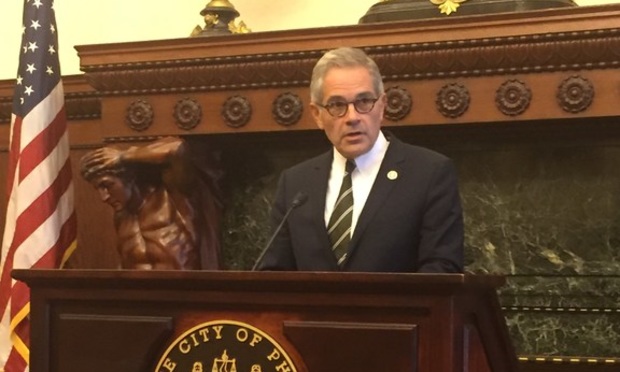

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner. (Photo: P.J. D'Annunzio/ALM)

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner. (Photo: P.J. D'Annunzio/ALM)

The mass exodus that rocked the Philadelphia legal community just days after District Attorney Larry Krasner took office has given rise to a series of employment discrimination lawsuits by ex-prosecutors.

Those actions may have serious hurdles to overcome, court watchers said, but they will likely provide some answers to lingering questions about why certain attorneys were fired and others were spared during the early days of Krasner's tenure.

Since early September, the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office has been hit with claims by three former assistant district attorneys, each of whom was let go in early January 2018 as part of a mass termination in which 31 lawyers were asked to leave. The three claims, brought in two separate lawsuits filed in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, each claim the DAO discriminated against them based on their age.

The first lawsuit was filed Sept. 5 by Sidney Gold of Sidney L. Gold & Associates and Robert Davitch of Sidkoff, Pincus & Green, on behalf of longtime homicide prosecutors Carlos Vega and Joseph Whitehead, who worked in several units including narcotics and homicide. Vega and Whitehead were 61 and 64, respectively, when Krasner asked for their resignations, and the resignations of 31 other former ADAs, on Jan. 5, 2018.

On Sept. 20, Michelle Seidner, who worked in the economic and cyber crime unit until she was terminated, joined Vega and Whitehead by filing similar age discrimination claims against the office in federal court. Kevin Console of Console Mattiacci filed her suit.

Both lawsuits reference public statements Krasner made both before and after taking office in which he allegedly indicated favoring younger prosecutors. The Vega/Whitehead suit cites an April 2018 radio interview in which Krasner allegedly said, "Some of the older ones, I mean let's be honest, it's hard to look back on your career and think that you were doing a good thing by stuffing so many people of color in jail."

At the time, Krasner's office declined to speak about any individual, but broadly branded the changes as necessary.

"Change is never easy, but DA Krasner was given a clear mandate from the voters for transformational change," former office spokesman Ben Waxman said in a 2018 statement to the press after the firings. "Today's actions are necessary to achieve that agenda. He looks forward to working as a team with the dedicated, talented, and hardworking employees of the DAO to make it the best prosecutorial office in the nation."

Employment attorneys, however, say the lawsuits are likely going to require the district attorney to provide more substantive reasons for who was fired and who was not.

"That's, ultimately what it's going to come down to," Steven Hoffman of the Allentown labor and employment firm Hoffman Hlavac & Easterly said. "If he felt they weren't going to follow his way of doing things, that would be legitimate nondiscriminatory way of doing things. If he was simply trying to clear out older folks, without doing any investigation about whether they were on board with his philosophies, that could raise a problem."

Employment lawyer Nancy O'Mara Ezold of Ezold Law Firm in Bala Cynwyd agreed that Krasner will likely raise the policy considerations as a defense, while the plaintiffs will likely raise questions about their individual merits as attorneys and why they were selected for termination.

"If they've been there a long time, and have lots of experience … then that is still a substantial claim because, why would an employer terminate a number of people in their 60s when they've likely had more experience than those who've been hired," Ezold said. "The defendant is going to have to show why they wanted, or did, replace more qualified people."

In an interview Wednesday, Gold and Davitch cited the allegations in their clients' complaint, and alleged that Krasner never interviewed their clients before they were told to leave.

"They were summarily terminated," Gold said. "He should have gotten those details at the time of the termination."

Gold also noted that his office represents three other ex-ADAs, but, he said, those cases are "not ripe for filing as of yet."

Neither Console, nor a spokeswoman for the district attorney's press office returned a message seeking comment.

Many of those fired in January 2018 were longtime members of the office and above the age of 40, which is the cutoff for being part of the protected class that can bring age discrimination lawsuits. Over the next 20 months, the District Attorney's Office brought in more than 100 attorneys, many of whom were recruited out of law school.

All of those factors, as well as Krasner's public statements referencing the mentality of older prosecutors versus younger lawyers, could make it unlikely the cases will be easily dismissed, attorneys said.

"In my view, in no way should any aspect of any decision be made using age as a factor," Andrew Abramson of Abramson Employment Law in Philadelphia said, speaking generally about employment discrimination cases. "If the assumption is the person, just because of their age, can't adapt to new ways, that's inherently discriminatory."

And, because the firings came less than a week into Krasner's tenure, attorneys also said the office won't be able to argue that the plaintiffs were given an opportunity to adjust, but failed.

However, Hoffman said that's where Krasner's experience as a defense attorney might come into play.

The defense, attorneys said, will want to point to specific reasons for why each attorney was viewed as unable to represent the new administration, and experiences Krasner may have had handling cases against the plaintiffs could count as the research required to make that argument.

"In some ways that's probably the best research—that you have first-hand knowledge in either their trial skills, or the way they treat plea bargains, or the way they charge," Hoffman said. "Usually it's good practice to give people some form of notice and opportunity to correct themselves, but that's usually when you're working for a steady employer versus a change of administration."

Along with the policy argument, employment attorneys noted the plaintiffs will have several other hurdles to surmount to be successful on their claims, including the fact that Krasner himself is in his late 50s, and he brought in numerous attorneys over the age of 40, including interim First Assistant Carolyn Engel Temin, who is in her 80s.

But those issues are also unlikely to shut down the cases, attorneys said.

"That's one fact that will be portrayed differently by the two sides," Ezold said about Krasner's age. "It doesn't mean you don't have a claim. It may be an extra hurdle, but it does not in and of itself, [end the claim]."

Under federal law, those who believe they've been subject to employment discrimination have 300 days to file their complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and in Pennsylvania, the deadline for filing with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission is 180 days. So either way, those who believe they were discriminated against during the January 2018 mass dismissal have likely already filed their claims.

Given the timing and the number of attorneys involved, court watchers said they would not be surprised to see more cases being filed in court soon.

"If these play out in court, that's going to be really interesting. I think the issue of policy versus the facts [in the individual's cases] might be very interesting," Ezold said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Stevens & Lee Hires Ex-Middle District of Pennsylvania U.S. Attorney as White-Collar Co-Chair

3 minute read

Judge Tanks Prevailing Pittsburgh Attorneys' $2.45M Fee Request to $250K

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1De-Mystifying the Ethics of the Attorney Transition Process, Part 2

- 2Being a Profession is Not Malarkey

- 3Bring NJ's 'Pretrial Opportunity Program' into the Open

- 4High-Speed Crash With Police Vehicle Nets $1.6 Million Settlement

- 5Embracing a ‘Stronger Together’ Mentality: Collaboration Best Practices for Attorneys

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250