Court Tackles Direct Wine Deliveries Amid COVID-19 Shutdown in Its First Livestreamed Session

"This may sound silly: Do you want us to stand up in our own houses when [the judge] comes on screen?" asked one of the lawyers in the case, which dealt with wine businesses who say they have no way to deliver products because of the Pennsylvania "stay at home" order.

April 28, 2020 at 06:35 PM

6 minute read

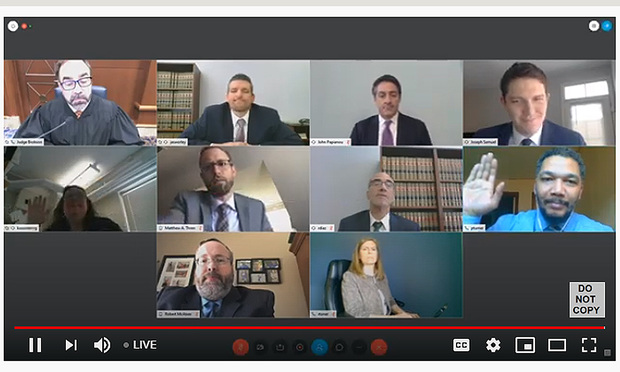

Commonwealth Court virtual proceedings. Photo: YouTube

Commonwealth Court virtual proceedings. Photo: YouTube

The YouTube channel was divided into nine panels, with six attorneys, one court crier and one court reporter looking on from different home offices. One panel was empty. That panel showed a black leather office chair and a wood paneled wall of a Commonwealth Court courtroom.

The chair remained empty as all the necessary players were getting ready to take part in the first livestreamed session of Pennsylvania's Commonwealth Court, which handles cases involving state agencies. After a brief explanation from the court crier, Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board Attorney Robert McAteer chimed in with a question.

"This may sound silly: Do you want us to stand up in our own houses when he comes on screen?" McAteer asked.

The question was the first of a handful of novel practical considerations that came before the court as it took its proceedings online in an effort to keep the wheels of justice moving while courthouses across the state remain largely closed to the public.

Much like the need to hold the proceedings online rather than in person, the only case on the court's virtual docket arose in large part from the public health concerns that have arisen out of the coronavirus pandemic, which has swept across the country.

The case, captioned MFW Wine v. Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board, deals with the Liquor Control Board's practice of barring specialty wine vendors from delivering special orders directly to customers, rather than through a state-owned liquor facility first. The plaintiffs, which consist of two wine sellers and a Philadelphia-area restaurant, argued that the practice, coupled with Gov. Tom Wolf's order from mid-March shutting down all state liquor stores, has effectively zeroed out their businesses, since sellers have no way to deliver products and the restaurants have no access.

The crux of the plaintiffs' complaint is that state liquor laws were recently changed to allow for direct deliveries of specialty products to customers, and that the PLCB has no discretion about whether to follow the order. The PLCB, however, has countered that recent changes to the fiscal code indicated that the board did not need to allow these direct deliveries.

The proceeding Tuesday was an evidentiary hearing, overseen by Judge P. Kevin Brobson. He was hearing the case in the court's original jurisdiction.

Brobson began the proceedings noting that the court was "making history" by holding the proceedings entirely virtually. He thanked Commonwealth Court President Judge Mary Hannah Leavitt, as well as the IT staff, saying they worked "'tirelessly" to implement a secure and user-friendly solution.

"Today we do what we have always done, just a little differently," Brobson said. "It's not a sign of what's to come, rather a sign of where we are."

Montgomery McCracken Walker & Rhoads attorneys John Papianou and Joseph Samuel represented the plaintiffs. Along with McAteer, attorneys Matthew Thren and Rodrigo Diaz represented the PLCB.

A partner at MFW Wines and the sole proprietor of A6 Wine Co., as well as the owner of Bloomsday Cafe, were sworn in over YouTube and took the virtual witness stand to make the plaintiffs' case.

Although the liquor control board has begun to reopen facilities, only one location in Philadelphia is handling specialty orders and only on a limited basis, according to the testimony. The plaintiffs testified those changes are not an adequate basis for the owners to begin rehiring all the employees they have had to lay off.

"I don't trust it will be able to consistently supply my operation," Zach Morris, owner of Bloomsday Cafe, said, noting that he has laid off all 40 of his employees.

Defense attorneys called several officials with the PLCB to give evidence as well. Each testified about alleged ambiguities of the law, the difficulties the department has faced operating under the partial shutdown, and the practical difficulties implementing direct delivery.

At one point, however, Brobson re-focused a line of questioning from a PLCB lawyer, saying the case would likely hinge on issues of agency discretion.

"You don't just throw your hands up in the air and say we don't know what the legislation means so we're just not going to do it," Brobson said. "I'm not sure that's going to be a persuasive argument."

Although several courthouses across the country have begun holding hearings and argument sessions online, Pennsylvania courts have remained mostly closed to the public. However, along with the Commonwealth Court hearing in MFW Wine, there were several signs Tuesday that restrictions for the judicial system are beginning to loosen.

Also on Tuesday, the Superior Court announced it would begin to hear oral arguments by phone starting April 30, and the Supreme Court also announced it was allowing local courts to begin restoring limited operations.

In a press statement announcing the Commonwealth Court's decision to livestream the hearing, Leavitt said moving the proceedings online was the best way to maintain both safety and address the issues before the court.

"This is an unprecedented time in our history, but the work of the court continues, making it imperative that we find ways to adapt to the new normal," Leavitt said.

The session Tuesday was not without a few technical hiccups. The initial link malfunctioned about a minute into the live stream, which required court officials to send out a second link shortly into the proceedings. At one point several participants also said they'd lost video feeds, and at other points a few noisy computers sidetracked the proceedings. One witness also had difficulty getting her video feed to work. But for the most part, the streaming was seamless.

Back before the proceedings officially began, when it came to the question about standing for Brobson as he entered the court, the court crier laughed and said no, attorneys could remain seated.

"We all may not be fully dressed appropriately for court from the waist down," he joked.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Court Sanctions Attorney $7.5K for Filing Repeated Erroneous Complaints

5 minute read

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1'Reverse Robin Hood': Capital One Swarmed With Class Actions Alleging Theft of Influencer Commissions in January

- 2Hawaii wildfire victims spared from testifying after last-minute deal over $4B settlement

- 3How We Won It: Latham Secures Back-to-Back ITC Patent Wins for California Companies

- 4Meta agrees to pay $25 million to settle lawsuit from Trump after Jan. 6 suspension

- 5Stevens & Lee Hires Ex-Middle District of Pennsylvania U.S. Attorney as White-Collar Co-Chair

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250