Philadelphia-Based Feds Have Ramped Up Prosecutions Against Lawyers

"I find these cases professionally offensive," said U.S. Attorney William McSwain of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. "They're damaging to our profession. When you have lawyers taking advantage of people, especially their own clients, that is really reprehensible conduct."

May 20, 2020 at 02:41 PM

4 minute read

William McSwain.

William McSwain.

The region has seen a recent spike in prosecutions against misbehaving attorneys by the Philadelphia-based branch of the Justice Department, and it's no coincidence, according to U.S. Attorney William McSwain of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

In an interview with The Legal, McSwain, the top federal prosecutor for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, acknowledged the rise in prosecutions against attorneys for white-collar crimes over the past year and a half and said he has made going after these lawyers a priority for his office.

Unlike a county district attorney's office, federal prosecutors have discretion to pick and choose which cases they deem most important. For McSwain, lawyers engaging in criminal behavior is particularly reprehensible.

"I find these cases professionally offensive," McSwain said. "They're damaging to our profession. When you have lawyers taking advantage of people, especially their own clients, that is really reprehensible conduct."

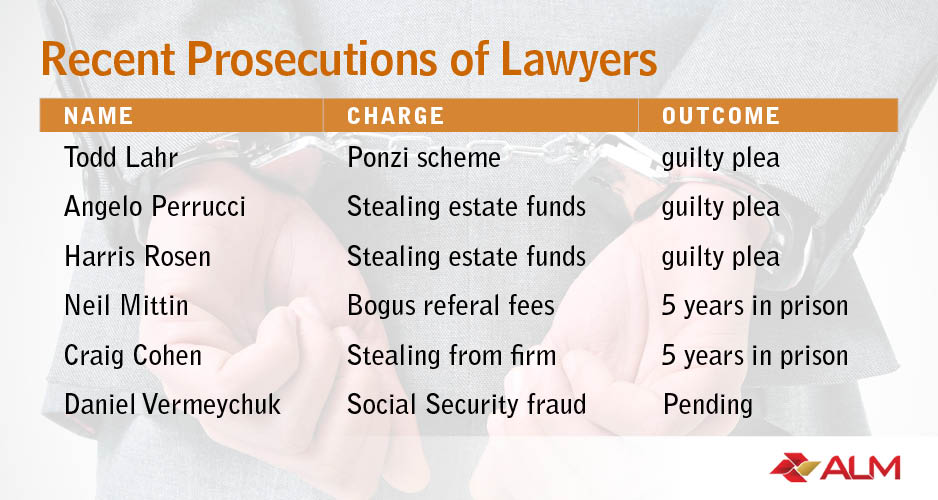

Most of the prosecutions involve attorneys ripping people off: take, for example, the case of Lehigh Valley lawyer Todd Lahr, who pleaded guilty to running a Ponzi scheme that duped his clients out of $2.7 million. Lahr convinced his clients to invest their money in a variety of business ventures, including a mining operation in Papua New Guinea, but instead used the money to pay his home mortgage, his child's school tuition, utility bills and other personal debt.

Or the case of Craig Cohen, of Blue Bell, an ex-White & Williams lawyer who was sentenced to five years in prison for scamming product manufacturers and class action settlements out of $3.4 million. Philadelphia personal injury lawyer Neil Mittin was sentenced to five years in prison and ordered to pay $3.4 million in restitution for collecting bogus referral fees.

John Kelvin Conner was sent to prison for gambling away an elderly client's savings. Conner, the client's power of attorney, made 176 unauthorized withdrawals at SugarHouse Casino in Philadelphia as well as the Borgata and Tropicana casinos in Atlantic City, totaling $95,000. His client's sole income was a monthly pension that went toward medical care and home assistance.

And so on.

McSwain said the cases are not just about fraud: "You have a lawyer who's supposed to be a trusted professional and who's held to the highest ethical standards and supposed to be leading the charge" for justice.

White-collar defense attorney and former federal prosecutor Linda Dale Hoffa said U.S. attorney's offices will typically pursue the most egregious cases to set an example.

"The amount of the [monetary] loss will not be a factor so much as an attorney doing a crime and abusing his special skill to commit the crime," she said.

Dale Hoffa added that it's not uncommon to see professionals of every stripe using their skills for criminal activity—and for that reason, the hammer comes down especially hard on them.

"Those with special skills like CPAs or doctors, they are particularly suited to commit crimes because of their special training, and it is viewed by prosecutors as an especially heinous crime. And they want to be clear, as a deterrent to others, that as a professional you are at a greater risk of being charged federally," she said.

"For these lawyers there will be very serious collateral consequences with the disciplinary board and they are at serious risk for losing their license," she added.

By the time a lawyer's misdeeds have reached the state's attorney disciplinary board, they've usually already been prosecuted.

The chairman of the board, James Haggerty, said the role of that organization is less about punishment and more about looking out for clients.

"The entire purpose of the disciplinary system is the protection of the public at large, not punishment of misbehaving attorneys," Haggerty said. "Everything we do is geared toward protecting the public. In order to do that, if that means recommending to the court that they suspend someone's license, then we'll do that."

He added, however, "The court does not look favorably upon any attorney who converts client money to their own use, and even less favorably upon lawyers who use their position to engage in such schemes."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Class Action Settlements Totaled $40B+ Three Years in a Row: 'We’re in a New Era'

5 minute read

AI's Place in Big Law Broadens, As Firms Embrace Fresh Uses of the Technology

Ballard Spahr Aims to Balance Hybrid Work With Relationship Building in Training New Associates

5 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250