Economic Tools for Improving Negotiation Outcomes

For deal lawyers, no matter the stripe, negotiations can sometimes feel rote. Clients may have a list of "must-haves," stock provisions approved by committee, or regulatory imperatives, on the one hand, and almost everyone knows—depending upon the type of deal—the flashpoints in a given transaction, on the

June 09, 2020 at 01:38 PM

6 minute read

Christopher Couch of McGlinchy Stafford (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

Christopher Couch of McGlinchy Stafford (Photo: Courtesy Photo)

For deal lawyers, no matter the stripe, negotiations can sometimes feel rote. Clients may have a list of "must-haves," stock provisions approved by committee, or regulatory imperatives, on the one hand, and almost everyone knows—depending upon the type of deal—the flashpoints in a given transaction, on the other. This can lead to sub-optimal outcomes—measured in terms of excessive expense or unwieldy implementation, particularly in an environment where clients sometimes view "success" as a signed-up deal, regardless of terms that made it into the transaction documents.

While not all deals need the same amount of preparation and rigor—as one of my former partners liked to say, "You don't always have to drive a Cadillac; sometimes a Buick is fine"— there are a few steps negotiators can take in every deal to improve outcomes. Some are proactive, some reactive, and most have little to do with "law." As noted in Rule 2.1, however, clients may benefit from a lawyer's reference "not only to law but to other considerations such as moral, economic, social and political factors." See Model Rules of Prof'l Conduct R. 2.1. Each tool discussed below falls into the "other considerations" category and can enhance the quality of the negotiation experience and client outcomes.

Tool No. 1—Prepare

It may sound so simple as to be meaningless, but preparing for negotiation means more than looking over a term sheet, collecting deal points from a client or reviewing a counterparty's draft agreement. Negotiation preparation requires, among other things, an understanding of the client's and counterparty's goals; the legal framework in which the parties are operating and constraints the framework imposes on the parties; the relative bargaining power of the parties; the client's alternatives to the deal; the client's particular sensitivities to and risk around certain topics (e.g., confidentiality, deal timing, price sensitivity, performance risk). Most negotiations have multiple outcomes, and each falls along a spectrum of acceptability for the client. Understanding the parties' goals and the client-counterparty dynamic can be just as important to a successful negotiation as understanding the applicable legal framework, and can help in mapping out likely outcomes.

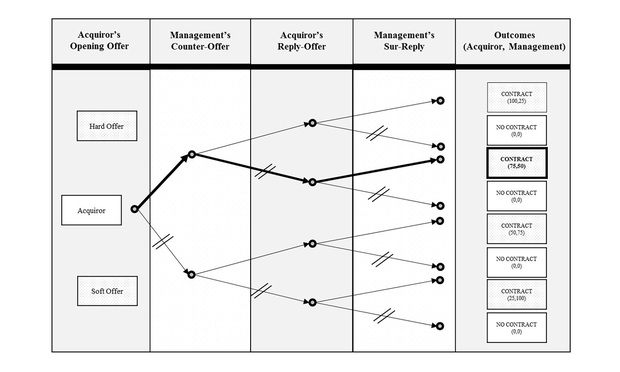

Tool No. 2—Make a Decision Tree

Two-party negotiations generally unfold as what economists call "sequential games." That is, one party starts, the other responds, the original party replies, etc., and the cycle continues until a deal is reached or the negotiation abandoned. The primary strategy for solving sequential games is backward induction. That is, "reason forward and look back." See Luke Froeb a, Brian T. McCann, Michael Shor and Michael R. Ward, "Managerial Economics: A Problem Solving Approach 170″ (3rd ed. 2014). This approach involves visualizing an outcome and working backward through the decision sequence to map out what must occur to achieve the outcome. The resulting diagram is a decision tree, with the branches representing choices to be made or avoided in order to achieve the sought-after outcome. By working backward, you can anticipate responses and counter-offers from your counterparty and visualize the path toward your preferred outcome.

Each move has associated with it a payoff, whether positive or negative. The goal of the decision tree is to maximize your payoff. Where your counterparty's payoff is also positive, there is a higher likelihood of reaching an agreement. Mapping out payoffs and the path toward them functions as a roadmap for the negotiation and, thus, increases the chance of a successful outcome.

Consider, for example, a negotiation involving the retention of a management team post-acquisition. Current management is important to the acquirer, but it does not want to overpay. Members of management want to remain, however, so everyone benefits from making the contract. Likewise, failing to reach an agreement hurts everyone. Under these circumstances, the decision tree may look something like this:

As noted, Acquiror wants to keep management but not over-pay (here, "overpay" means the management's payoffs exceed Acquiror's). Similarly, m anagement wants a deal, but not an abusive one (here, "abusive" means all of the gains of trade accrue to one party of the other). Because it is in everyone's interest to reach an agreement (i.e., there are some baseline benefits to each side regardless of the type of agreement), only payoffs above the "baseline payoff" are considered in calculating "gains." Similarly, because it is in everyone's interest to reach an agreement, only "contract" outcomes are considered for mapping outcomes.

Taking all of this into consideration, Acquiror should "reason forward" to "contract" outcome No. 2. In this outcome, Acquiror does not overpay and realizes most—but not all—gains of trade. To reach this goal, Acquiror should open with a "hard offer" and stick with that approach throughout the negotiations, understanding that management, not wanting to feel abused, is likely to reject the initial offer and counter.

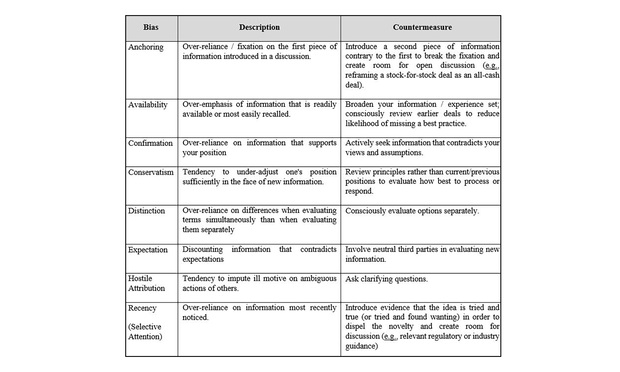

Tool No. 3—Check Your Bias

Each of us suffers from bias. In the negotiation context, think of bias as rules of thumb that help us to make decisions quickly based on experience. See, e.g., Daniel Kahneman, "Thinking Fast and Slow" (2011). In a repeatable process like negotiation, however, "good decisions" are not those that yield positive outcomes; rather, they are the product of processes that reliably produce the desired outcomes. See, e.g., Jim Paul & Brendan Moynihan, "What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars" (Columbia Business School Publishing 2013). Good decisions come from objective and rigorous processes designed to accommodate and adapt to new information. Good decisions are objective and replicable (regardless of outcome), not the product of intuition or "gut feeling." Bias, then, is the opposite of good decision making, even though the results in many instances may be similar. Bias distorts decisions and makes desired outcomes in any particular negotiation less certain. In the negotiation context, the following biases are common and should be realized (and guarded against):

McGlinchey Stafford graphics

McGlinchey Stafford graphicsAs should be apparent from the above, one of the most important elements of any successful negotiation is the recognition it is a deliberate process. So viewed, it is easy to see that preparation, anticipation, and awareness are critical to success and—when practiced over time—will consistently improve client outcomes.

Christopher Couch is a partner in McGlinchey Stafford's banking and corporate practices, where he advises and represents clients in transactional matters involving technology acquisition, corporate finance, mergers and acquisitions.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Products Liability: The Absence of Other Similar Claims—a Defense or a Misleading Effort to Sway a Jury?

K&L Gates Sheds Space, but Will Stay in Flagship Pittsburgh Office After Lease Renewal

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250