California Law Deans React to Lack of Movement on Passing Bar Exam Score

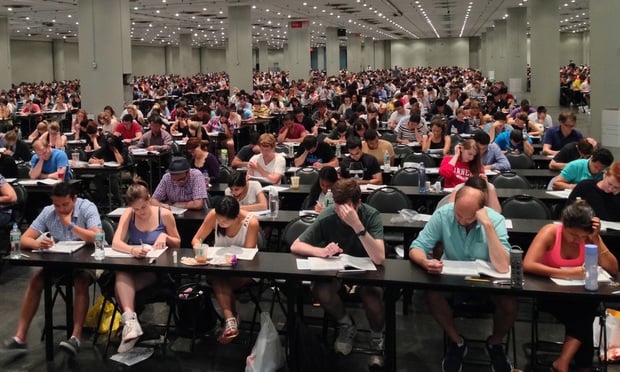

The California Supreme Court announced Wednesday afternoon that it would not change the passing score on the state's bar exam.

October 19, 2017 at 04:47 PM

11 minute read

The California Supreme Court announced Wednesday afternoon that it would not change the passing score on the state's bar exam.

The decision came despite calls from across academia to lower the so-called “cut” score, the nation's second-highest behind only Delaware. The Law School Admission Council Inc., a California State Bar committee stocked with law school deans, recommended in August that the Supreme Court reduce the bar exam passing score by up to 6.25 percent.

In Wednesday's letter announcing the decision, California's supreme court justices called on the state bar and law school deans to work together to determine what, if any, portions of the state's bar exam should be modified. In the wake of the court decision, The Recorder reached out to law school deans across the state to get their reactions to the Supreme Court's move—or perhaps more accurately lack thereof—and suggestions for next steps.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Jennifer Mnookin, UCLA

I'm deeply disappointed by the court's decision not to support an interim change to the cut score. There's no evidence that California's current, atypically high cut score produces better lawyers. I, and virtually all my fellow law deans, strongly believe that the current cut score hurts California law students, the diversity of California's lawyers, and that it has far more costs than benefits to our state as a whole. I'm sorry that the court didn't reach a similar decision.

It is absolutely critical to emphasize that our responsibility is not to teach to the test; it is to develop lawyers and leaders in the law. The bar is only one piece of that training, and it's certainly not the only important one. One of the problems with the unjustifiably high cut score is that it risks making the bar exam too much of a direct focus for legal education.

Just Tuesday, I was speaking with a group of successful lawyers who were complaining that law students sometimes take too many so-called “bar courses” at the expense of other courses that would actually be more valuable to them in the real world of law practice. The too-high cut score encourages law students to do precisely that—it may help them on the bar, but hurt them in their professional development and training for lawyering.

David Faigman, UC-Hastings

I was profoundly disappointed in the court's decision. I appreciate that the court contemplated future work that might lead to a more justified cut score and I expect to be involved in that work. However, the court's opinion-letter completely failed to engage the substantive policy issues that are presented by this important matter as they arise today.

The court recognized that the 1440 score that is currently employed was without empirical basis. It also noted, correctly, that the significantly lower cut scores used by virtually all other states similarly lack an empirical foundation. So this decision simply keeps in place the status quo, but without explanation of what—besides historical practice—justifies it.

This practice, we now know, operates as a substantial barrier to entry, one that has a significant disparate impact on minority candidates to the bar. I found it unfortunate, to say the least, that the court's opinion-letter did not grapple with these difficult issues. Instead, it simply offered conclusions, without analysis.

Stephen Ferruolo, University of San Diego

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Crypto Industry Eyes Legislation to Clarify Regulatory Framework

- 2Sidley Adds Ex-DOJ Criminal Division Deputy Leader, Paul Hastings Adds REIT Partner, in Latest DC Hiring

- 3Justice Delayed is Justice Denied

- 4'It's a Matter of Life and Death:' Ailing Harvey Weinstein Urges Judge to Move Up Retrial

- 5Profits Surge Across Big Law Tiers, but Am Law 50 Segmentation Accelerates

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250