Serendipity and Internet Law: How the 'Zeran v. AOL' Landmark Almost Wasn't

Zeran v. AOL may not be a household name, but it is the Internet's most important landmark ruling. This seminal court case, which was the first…

November 10, 2017 at 02:45 AM

52 minute read

Zeran v. AOL may not be a household name, but it is the Internet's most important landmark ruling. This seminal court case, which was the first to consider the meaning and scope of §230 of the Communications Decency Act, has been a pillar of the legal framework that has permitted revolutionary services such as

Over the past two decades, Zeran has been cited in over 250 judicial opinions and discussed in hundreds of law review articles. Judge

But Zeran as we know it might never have happened. This essay examines various ways in which, if one or two stars had aligned differently, the first case decided under §230 would not have been Zeran, or at least not Judge Wilkinson's profound and broad landmark. These many layers of serendipity highlight how important legal developments—that in hindsight may be taken for granted—may be affected by seemingly small and even random events.

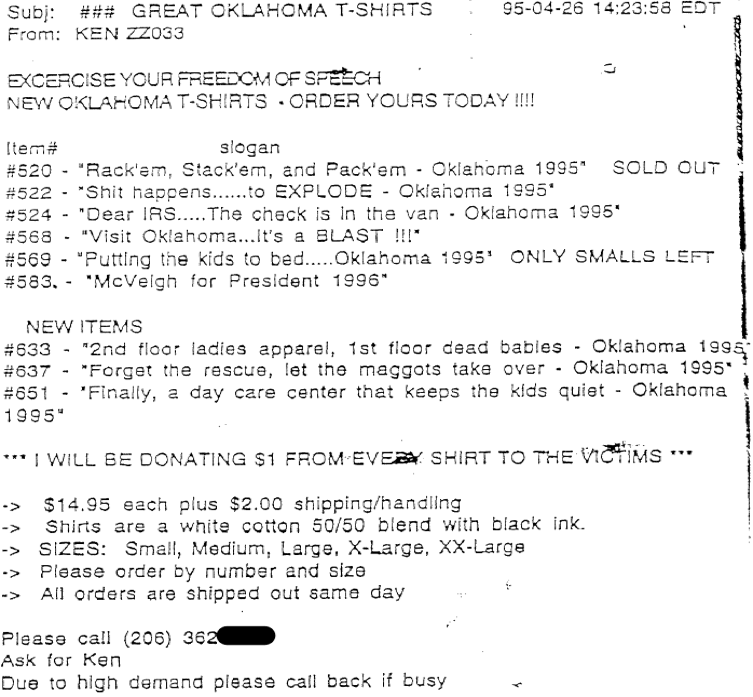

For starters, it took the bizarre, cruel, and persistent actions of an unidentified troll to set the ball in motion. Whatever motivated the “author” of the online postings that launched this controversy will probably never be known. But his or her impact on Internet law is now clear. In April 1995, six days after the terrorist bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City killed 168 people (including many children), this miscreant used a series of AOL screen names (including “Ken Z033” and “Ken ZZ03”) to post fake online advertisements for “Naughty Oklahoma T-shirts” purporting to celebrate the attack. T-Shirt “design #651,” for example, would read “Finally, a day care center that keeps the kids quiet – Oklahoma City 1995.” The slogan for “design #568” was “Visit Oklahoma . . . . It's a BLAST.” The ads directed viewers to call a phone number that Kenneth Zeran, a free-lance artist and film producer in Seattle who had never been an AOL subscriber, used for his home office. The ads told them to “ask for Ken,” and added that, “due to high demand please call back if busy.” There has never been any hint of why the unfortunate Mr. Zeran was targeted.

The cruel hoax might never have led to litigation if the fake ads had not gained notoriety outside whatever subset of AOL users (who then numbered around 2.5 million) might have encountered them on the AOL “classifieds” bulletin board where they were posted. But four days after the first ad appeared, someone emailed one of the ads to Mark Shannon, then the co-host of a popular morning radio show (“Shannon & Spinozi”) on KRXO-FM in Oklahoma City. And two mornings later, while on-air, Shannon “read out the slogans purportedly displayed on the Oklahoma City T-shirts, attributed these slogans to Ken at the telephone number of Ken Zeran, characterized the person who did this as 'sick', and incited the audience to call” Ken. That broadcast, which Zeran's lawyers later described as “devastating,” itself was not pre-ordained. Shannon had had the good sense to try to contact Zeran directly before the fateful broadcast. But there was yet another stroke of horrible bad luck for Mr. Zeran—and another bit of serendipity that pointed this controversy toward the courts: Shannon was unable to get through to him.

Just shy of a year later (on April 23, 1996), Mr. Zeran did, of course, commence litigation in federal court against AOL. But he did not sue AOL in a forum that was likely to lead to an appellate decision in the Fourth Circuit, where Zeran was ultimately decided. Nor did he sue in his home district in Washington state. Had he done so, any appeal in the case would have gone to the Ninth Circuit. Instead, he sued AOL in federal court in Oklahoma City, the same place where, three months earlier, he had sued Diamond Broadcasting, owner of KRXO-FM. Perhaps his lawyers initially sued Diamond/KRXO in Oklahoma City because they were concerned about whether it could be successfully hauled into court in Seattle, and then chose the same venue for the suit against AOL as a matter of efficiency. Or, perhaps, they expected jurors from Oklahoma would most readily sympathize with a plaintiff who had been victimized by a grotesque stunt that mocked the unspeakable tragedy that had occurred there.

If AOL had accepted Mr. Zeran's choice of venue, his case would never have come before Judge Wilkinson, and any appeal would have gone to the Tenth Circuit. That course was averted, however, because AOL's initial move was a motion that, in addition to seeking dismissal for improper venue and failure to state a claim, requested, in the alternative, a transfer to the Eastern District of

If Zeran's lawyers had sued Diamond/KRXO and AOL in a single lawsuit—which would have been perfectly natural, and which they unsuccessfully tried to accomplish after-the-fact by asking the Oklahoma judge to consolidate the two cases, the case probably would have stayed put in Oklahoma. Given the hoaxster's disgusting statements about the Oklahoma City bombing, one can only wonder whether an Oklahoma-based court would have had greater skepticism for AOL's novel §230 defense than the judges who in fact adjudicated the case: District Judge T. S. Ellis in Alexandria,

Aside from uncertainties regarding whether and where any claims by Mr. Zeran would be litigated, it was far from certain that the litigation would revolve around §230. In fact, as of late April 1995, when the fake ads appeared on an AOL bulletin board, §230 —along with the rest of the Communications Decency Act and the rest of the Telecommunications Act of 1996—was not even on the books. Indeed, those unfortunate events occurred a full two months before Representatives Christopher Cox (R-Cal.) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced the original predecessor to §230, a bill called the “Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act” (H.R. 1978). And it would still be another seven months, until February 8, 1996, before the CDA, including the final version of §230, would be enacted and take effect.

Mr. Zeran waited until April 23, 2016—two days before the one-year anniversary of the posting of the first fake ad and eleven weeks after §230 was enacted—before suing AOL. Perhaps his lawyers were focused on the one-year statute of limitations for defamation actions under the laws of many states (including Oklahoma and

Both Judge Ellis and the Fourth Circuit later held that AOL's ability to invoke §230 in Zeran turned on the timing of the suit. Focusing on the language of what was then §230(d)(1)—“No cause of action may be brought and no liability may be imposed under any State or local law that is inconsistent with this section”—the Fourth Circuit held that “Congress clearly expressed its intent that the statute apply to any complaint instituted after its effective date, regardless of when the relevant conduct giving rise to the claims occurred.” Absent that holding and some fortuitous timing, Judge Wilkinson and his colleagues would never have reached the merits of AOL's §230 defense.

The Oklahoma City lawyers who originally represented AOL in Zeran and succeeded in having the case transferred were aware of §230's enactment. They briefly discussed the statute in the “merits” portion of the briefs supporting the motion to dismiss they filed in federal court in Oklahoma. Yet far from recognizing this might be a ground-breaking case about the meaning of the brand-new statute, they did not argue that the statute actually applied to the case. Instead, apparently because §230's enactment post-dated the conduct at issue, they expressly conceded that “[t]he Act may not operate to control the events upon which this lawsuit is based unless it is found to be retroactive.” They offered no argument at all regarding why §230 should control despite the timing of its enactment.

The arguments for dismissal that AOL's Oklahoma counsel did make focused on principles of negligence under Oklahoma common law, including duty, foreseeability, and non-liability for the deliberate acts of a third party. They briefly alluded to the First Amendment. And, under the heading “Recent Developments in the Law of Cybertorts,” they contrasted the 1991 decision by a federal district judge in Cubby v. Compuserve with the 1995 decision by a

After the case traveled east, serendipity struck even in the way

The process AOL used to select new counsel for the case was an in-writing “beauty contest.” The in-house lawyers, Randall Boe and Blumenfeld, asked Wilmer and two other Washington law firms known for their significant media litigation practices to each submit a written proposal setting out a strategy for defending the case and an estimate of fees. Carome and two of his colleagues, John Payton and Samir Jain, dove into the exercise. Even though AOL had already used its one shot at a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule 12(b)(6), and even though its Oklahoma counsel had come close to conceding that §230 was inapplicable to the case, the Wilmer team devised a strategy to bring §230 front and center. Specifically, the team proposed that AOL (1) file an answer asserting §230 and the First Amendment as affirmative defenses, (2) move for judgment on the pleadings under Federal Rule 12(c) based solely on §230, and (3) argue in that motion that application of §230 would not be impermissibly “retroactive.” Wilmer also proposed a loss-leading fixed fee: $50,000 to defend the case through a decision on the proposed Rule 12(c) motion. Even 20 years ago, that was an aggressively low figure, especially because that fee would also have to cover Wilmer's handling of many other tasks, including responding to pending discovery requests and taking Mr. Zeran's deposition, which had to be done quickly to meet the demanding pretrial schedule set in the Eastern District of

Based on the competing firms' written submissions and some follow-up telephone calls, AOL retained Wilmer. At least one of the other firms did not mention the §230 defense in its proposed case strategy. A reliable source recently said that AOL asked one or both of the other two firms to match Wilmer's proposed fee, but they did not. Wilmer's §230-centric strategy also was important to AOL, which was keenly aware of the broader significance of this case to its business model. That strategy prevailed, both before District Judge Ellis and, ultimately, in the Fourth Circuit. Had Wilmer not been invited to pitch for the representation, or if AOL had chosen different lawyers, might the path and outcome have varied?

Nor, of course, was the role of the most important figure in this story—then Chief Judge Wilkinson—preordained. As of July 1997, when briefing of the appeal was completed, there were 16 judges on the Fourth Circuit (three of whom were on senior status), any of whom (absent a conflict of interest) could have been assigned to the case. In 1997, the Fourth Circuit issued 283 published decisions. Judge Wilkinson participated in 61 of them, and he wrote an opinion for the court or a concurrence in 33, with 24 for a unanimous court. So, when the long chain of events described above finally landed Zeran in the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, the statistical chance that Judge Wilkinson would cast a vote in the case was at best one in five. And if there was to be a published decision from the Fourth Circuit in the case, the statistical chance (as of the time the appeal was filed) that it would turn out to be a unanimous opinion penned by Judge Wilkinson (as occurred in Zeran) was less than one in 10.

As Carome, his colleague Samir Jain, and AOL in-house counsel Randall Boe awoke in Richmond on October 2, 1997, none of them knew (or could know) which judges would be present when Zeran was called for oral argument later that morning. The Fourth Circuit's protocol was then (and is now) not to announce the composition of its panels until the morning of oral argument. The first thing Carome did after checking in with the clerk's office that morning was to go to a courthouse telephone booth to dial a colleague back in Washington, to get a quick read on the three judges he had just learned would hear the case: Chief Judge Wilkinson; Circuit Judge Donald S. Russell; and, sitting by designation, Judge Terrence Boyle, then the Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina. Carome worried about the seemingly conservative bent of the panel—two Reagan appointees (Wilkinson and Boyle) and a Nixon appointee who before Watergate had served as a legislative assistant to U.S. Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC). He also worried whether any of the members of the panel had familiarity with an interactive computer service such as AOL, CompuServe, or Prodigy. All three judges had been on the bench since at least 1984, well before the popularization of email and the Internet. Judge Russell was 91 years old, and his appointment to the court (in 1971) predated “the first public demonstration of the ARPANET.”

One potentially hopeful note Carome gleaned from his team back in Washington was that Judge Wilkinson had a newspaper background. In between stints as a law professor at

Having Judge Wilkinson on the panel, and having him be the author of the decision in favor of AOL, was no guarantee that the case would produce the broad, plain-spoken holding of Zeran that has been cited so often over the past twenty years: “By its plain language, § 230 creates a federal immunity to any cause of action that would make service providers liable for information originating with a third-party user of the service.” Judge Wilkinson and his colleagues might have hewn more closely to the ideal of judicial minimalism, heralded by scholars such as Harvard Law Professor Cass Sunstein, which expects judges to issue narrow rulings confined to the facts at hand. The opinion in Zeran may not have strictly adhered to that approach, broadly declaring websites immune from so-called “distributor liability” (i.e., the sort of notice-based liability that the First Amendment might allow the law to impose on a bookseller) and declining to confine §230 to only defamation claims. While the opinion was both brilliant and correct, a narrower ruling could have emerged. Fortunately, Judge Wilkinson instead took a deep interest in the case and issued a well-reasoned and sweeping opinion. Both in the case at hand and for years to follow, this ruling by a highly regarded conservative jurist, who was then Chief Judge of a conservative court, has ensured that §230 has had the effect Congress intended: lifting what would otherwise be, in Judge Wilkinson's words, “an impossible burden in the Internet context.”

After the Fourth Circuit's decision, the case was not entirely over. Mr. Zeran filed a cert petition for review in the Supreme Court. It seemed highly unlikely that the high Court would take an interest in the case. As this was the first case to construe §230, there obviously was no conflict among appellate courts, and the Supreme Court rarely engages in mere error correction. The Wilmer team and AOL advised the Supreme Court that it would not submit a brief in opposition to Mr. Zeran's petition. But on April 21, 1998, three years to the week after the posting of the fake T-shirt ads, the Supreme Court called for a response to Mr. Zeran's petition. The uncertainty finally ended two months later, when the Supreme Court denied the petition, leaving Judge Wilkinson's landmark opinion in place as a steady and bright—but perhaps not foreordained—beacon to lead other courts across the country.

* * *

In an alternate universe in which the Zeran landmark never materialized, the first judicial decision addressing the scope of §230 probably would have come from a state court in a case involving the “third rail” of child pornography. Captioned Doe v. AOL, that case was filed in the Circuit Court for Palm Beach County, Florida, on January 23, 1997. That was exactly nine months after Mr. Zeran sued AOL, and about ten months before the Fourth Circuit's Zeran decision. After Zeran, Doe v. AOL was the next case to be filed anywhere that would produce a reported court decision construing §230. It also was the only other case to reach and resolve the “retroactivity” question that was decided in Zeran.

The plaintiff in Doe v. AOL was a mother, referred to as Jane Doe, suing on behalf of herself and her minor son, John Doe. The defendants were AOL and an AOL user named Richard Lee Russell. If the facts in Zeran were very bad, the facts in AOL v. Doe were horrible. In 1994, Russell, a neighbor of the Does, allegedly lured John Doe, then eleven years old, and two other boys to engage in sexual activity with each other and with Russell. Russell allegedly photographed and videotaped those acts, and then used AOL chat rooms to market those materials to other pedophiles, resulting in the sale of at least one of the videos. By the time the suit was filed, Russell was in federal prison based on these activities. Jane Doe alleged that AOL had known that its chat room feature was being used in this manner by pedophiles. One of the more memorable refrains of her court papers was that AOL had knowingly allowed its chat rooms to become the “Home Shopping Network” for child pornography. She asserted claims for negligence and negligence per se, referencing Florida criminal statutes prohibiting the sale or distribution of obscene materials. AOL could not remove the case from state to federal court because there was no diversity of citizenship (both Jane Doe and Russell were from Florida) and because the availability of a federal defense generally does not provide a basis for federal question jurisdiction.

As in Zeran, AOL retained Wilmer to defend Doe, and once again the defense strategy focused on §230. At each step of Florida's multi-level court system, the presiding judges could look to, and rely on, Zeran as a basis for dismissing all of the claims asserted against AOL. In June 1997, the Florida Circuit Court (the trial-level court) granted AOL's motion to dismiss based on §230, citing Judge Ellis' three-month-old decision in Zeran. Jane Doe promptly appealed to the Florida District Court of Appeal. In October 1998, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeal affirmed “[f]or the reasons expressed in Zeran.”

Although the Florida Court of Appeal's decision in Doe was unanimous, it nevertheless called for the Florida Supreme Court to examine the case. “[D]eem[ing] the questions raised as to the application of §230 of the Communications Decency Act to be of great public importance,” it certified to the state high court three questions: whether §230 applies in cases where the events predate the statute's effective date, whether §230 preempts Florida law, and whether §230 provides immunity to a computer service provider that had notice of the allegedly unlawful postings.

By a bare 4-3 vote, the Florida Supreme Court approved the decision of the Court of Appeal. The majority's decision closely tracked Zeran's reasoning and block-quoted large swaths of Judge Wilkinson's opinion. Aligning with Judge Wilkinson, the slim majority held that “the gravamen of Doe's alleged cause of action” was “liability based upon negligent failure to control the content of users' publishing of allegedly illegal postings,” which are “analogous to the defamatory publication at issue in the Zeran decisions.”

Would the final vote in Doe v. AOL have been the same if Zeran had not already blazed the trail? The facts were arguably more shocking than in Zeran. Perhaps one of the justices of the Supreme Court of Florida would have tipped to weighing Floridian interests more heavily than federal interests. Even with the benefit of Zeran, the three dissenting justices met the majority with stinging disagreement. Justice Richard

* * *

Judge Wilkinson got it absolutely right in Zeran. And, we are confident that, even if the Zeran landmark had never materialized, the courts of the United States nevertheless would ultimately have reached a consensus in construing §230 to provide broad immunity for online intermediaries, as Congress intended. But the path to that outcome might have been more difficult and tortured if the first appellate decision interpreting the statute had come from a less bold, brilliant, and respected jurist than Judge

Patrick J. Carome is a partner and Cary A. Glynn was a summer associate at

This essay is part of a larger collection about the impact of Zeran v. AOL curated by Eric Goldman and Jeff Kosseff.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

California’s Workplace Violence Laws: Protecting Victims’ Rights in the Workplace

6 minute read

'Nothing Is Good for the Consumer Right Now': Experts Weigh Benefits, Drawbacks of Updated Real Estate Commission Policies

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250