Plaintiffs Aim to Salvage Class Action Against Milberg After SCOTUS Ruling

Plaintiffs lawyers are asking an appeals court to reinstate certification of their class-action legal malpractice lawsuit against Milberg and its lawyers, insisting that a U.S. Supreme Court decision earlier this year didn't derail their case.

November 14, 2017 at 07:25 PM

20 minute read

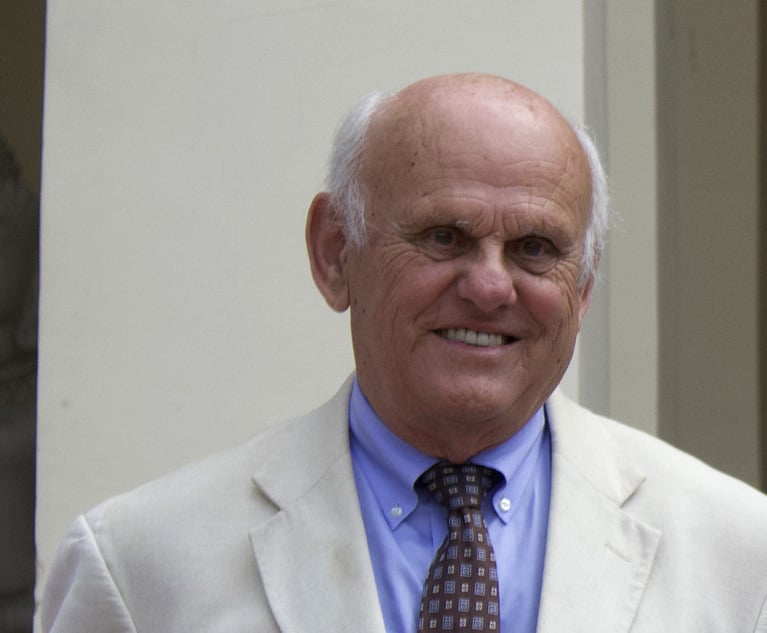

Gregory P. Joseph.

Gregory P. Joseph. Plaintiffs lawyers are asking an appeals court to reinstate certification of their class-action legal malpractice lawsuit against Milberg LLP and its lawyers, insisting that a U.S. Supreme Court decision earlier this year didn't derail their case.

In a Nov. 9 filing, attorney Lawrence Kasten wrote that the facts of his case don't parallel that of Microsoft v. Baker, a June 12 decision in which the Supreme Court blocked a controversial procedural tool used by plaintiffs to appeal class certification orders by voluntarily dismissing their own case. Appealing class certification is critical to both sides because those decisions often make or break a case.

Kasten represents Lance Laber, a purported class member in the Milberg case, who appealed an Arizona judge's 2012 decision not to certify the class. In 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit vacated that order, and Milberg petitioned the Supreme Court to take up the case. On June 19, the Supreme Court granted the petition, then vacated the Ninth Circuit's order for further consideration in light of Microsoft.

Kasten wrote that his case is different: In Microsoft, the lead plaintiff voluntarily dismissed his case so that he could appeal final judgment, but in the Milberg case, Laber was an intervenor—not one of the original two plaintiffs who voluntarily dismissed the case after they lost on certification.

“The path forged by Laber is not, in any sense, a functional equivalent to the 'we-pretend-to-dismiss-with-prejudice-but-do-not-really-mean-it' path pursued by Mr. Baker and his co-plaintiffs,” wrote Kasten, a partner at Lewis Roca Rothgerber Christie in Phoenix. Kasten referred a request for comment to his law firm colleague, Robert McKirgan, who didn't respond.

An attorney for the defendants, Gregory Joseph of Joseph Hage Aaronson in New York, declined to comment. His response brief is due on Dec. 4.

In Microsoft, the Supreme Court found the controversial tactic had violated Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(f), which permits interlocutory appeals of class actions, and wasn't a “final decision” under Judiciary and Judicial Procedure Code 1291. A concurring opinion found that under Article III of the Constitution, federal courts would have no jurisdiction over cases once plaintiffs dismissed their claims.

Several cases have been stayed in light of Microsoft, which reversed a Ninth Circuit decision. Days after the ruling, Eli Lilly & Co. moved to dismiss a long-standing appeal in a case brought by a class of consumers who used Cymbalta, an antidepressant prescription drug. The Ninth Circuit granted dismissal of the case on Oct. 12.

The Milberg case dates back to 2001, when the securities firm represented a nationwide class of investors who sued Variable Annuity Life Insurance Co. Inc. in Arizona federal court. A judge certified the class but ended up vacating that order after Milberg missed several disclosure deadlines in 2004, prompting judgment against the plaintiffs, according to court filings. In 2009, two purported class members, including Columbia Law School professor Philip Bobbitt, brought the legal malpractice case, which sought to certify the same class that had been in the insurance case.

The case named Milberg, one of its attorneys, Michael Spencer, who is of counsel, and four former attorneys: firm co-founder Melvyn Weiss, who spent 18 months behind bars after pleading guilty to charges involving kickbacks to lead plaintiffs; Janine Lee Pollack, now a partner at Wolf Haldenstein Adler Freeman & Herz; Lee Weiss, now a partner at Berns Weiss; and Brian Kerr, now special counsel at Baker Botts. The suit also named three other law firms and their principals: Ronald Uitz, of Uitz & Associates in Washington, D.C.; Sheldon Lustigman and Andrew Lustigman, previously of The Lustigman Firm, and now at Olshan Frome Wolosky in New York; and Tucson's Gabroy Rollman & Bossé, now Bossé Rollman, and its partners Ronald Lehman and John Gabroy, now resigned.

But U.S. District Judge Frank Zapata of the District of Arizona declined to certify the legal malpractice case, concluding that the laws of the 50 states in which more than 1 million class members lived made the class too disparate to certify. The plaintiffs voluntarily dismissed their case with prejudice in 2013 after Zapata declined interlocutory appeal of his order.

In Laber's appeal, the Ninth Circuit vacated that order, concluding that the claims of all class members fell under the law of Arizona, where the alleged malpractice occurred.

On Oct. 10, the Ninth Circuit ordered both sides to address Microsoft.

In his brief, Kasten wrote the Supreme Court's 1977 holding in United Airlines v. McDonald “endorsed the procedure followed in this case,” in which an unnamed class member intervened to appeal a class certification order in a sex discrimination case brought by female flight attendants.

Microsoft, he wrote, “did not alter the viability of the procedure endorsed in United Airlines.”

But in United Airlines, Joseph wrote in his original answer brief in the case, the intervenor didn't know to act before judgment took place.

“That is emphatically not the case here,” he wrote. “Appellant was not blindsided. Following denial of the petition, appellant acted in concert with plaintiffs, through their shared counsel, to generate this appeal.”

Gregory P. Joseph.

Gregory P. Joseph. Plaintiffs lawyers are asking an appeals court to reinstate certification of their class-action legal malpractice lawsuit against

In a Nov. 9 filing, attorney Lawrence Kasten wrote that the facts of his case don't parallel that of

Kasten represents Lance Laber, a purported class member in the

Kasten wrote that his case is different: In

“The path forged by Laber is not, in any sense, a functional equivalent to the 'we-pretend-to-dismiss-with-prejudice-but-do-not-really-mean-it' path pursued by Mr. Baker and his co-plaintiffs,” wrote Kasten, a partner at

An attorney for the defendants, Gregory Joseph of Joseph Hage Aaronson in

In

Several cases have been stayed in light of

The

The case named

But U.S. District Judge Frank Zapata of the District of Arizona declined to certify the legal malpractice case, concluding that the laws of the 50 states in which more than 1 million class members lived made the class too disparate to certify. The plaintiffs voluntarily dismissed their case with prejudice in 2013 after Zapata declined interlocutory appeal of his order.

In Laber's appeal, the Ninth Circuit vacated that order, concluding that the claims of all class members fell under the law of Arizona, where the alleged malpractice occurred.

On Oct. 10, the Ninth Circuit ordered both sides to address

In his brief, Kasten wrote the Supreme Court's 1977 holding in

But in

“That is emphatically not the case here,” he wrote. “Appellant was not blindsided. Following denial of the petition, appellant acted in concert with plaintiffs, through their shared counsel, to generate this appeal.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Where Were the Lawyers?' Judge Blocks Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order

3 minute read

Netflix Music Guru Becomes First GC of Startup Helping Independent Artists Monetize Catalogs

2 minute read

K&L Gates Files String of Suits Against Electronics Manufacturer's Competitors, Brightness Misrepresentations

3 minute read

Holland & Knight Hires Former Davis Wright Tremaine Managing Partner in Seattle

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Who Are the Judges Assigned to Challenges to Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order?

- 2Litigators of the Week: A Directed Verdict Win for Cisco in a West Texas Patent Case

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Womble Bond Becomes First Firm in UK to Roll Out AI Tool Firmwide

- 5Will a Market Dominated by Small- to Mid-Cap Deals Give Rise to a Dark Horse US Firm in China?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250