In Contentious Pretrial Hearing, Judge Alsup Slams Uber Over Secretive Data Practices, Delays Trial

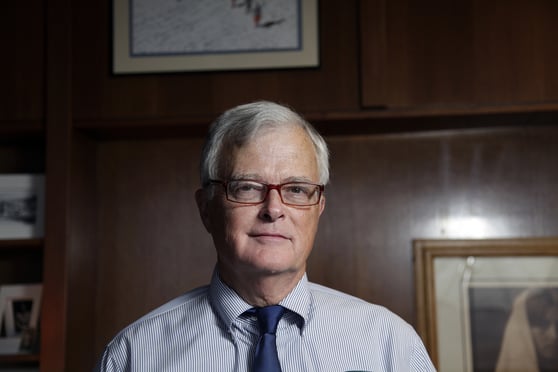

Judge William Alsup told Uber's legal team he can't trust what they say because they've "lied so many times."

November 28, 2017 at 12:41 PM

7 minute read

A letter written by a former Uber Technologies Inc. employee to an in-house lawyer has thrown a wrench into the company's blockbuster trade secrets battle with autonomous car rival Waymo.

During a pretrial conference Tuesday morning in San Francisco, Uber's former manager of global intelligence Richard Jacobs testified that Uber used encrypted messaging services and other techniques to keep intelligence on other companies off its server, where it could be found during litigation, and that he had informed in-house counsel at the ride-hailing company in a letter after he left the company about what he saw as ethically problematic practices.

U.S. District Judge William Alsup of the Northern District of California, who is presiding over the case, noted that the techniques could have been used by Uber to skirt its obligation to hand over information to Waymo and he delayed the trial, which was due to begin next week.

“If even half of what's in that letter is true, it would be a huge injustice to force Waymo to go to trial without the things that were said in that letter,” Alsup said. “Uber lawyers withheld evidence. To have hidden this from a lawyer and a judge, it's just, it's so upsetting.”

Uber's lawyer, Arturo González of Morrison & Foerster, asserted that no one on his team knew about the letter or its allegations before Alsup did.

An Uber spokesperson said in a statement Tuesday afternoon that none of the testimony at the hearing “changes the merits of the case.”

“Jacobs himself said on the stand today that he was not aware of any Waymo trade secrets being stolen,” the statement added.

Alsup called Jacobs in to testify after he received a letter on Nov. 22 from the local U.S. Attorney's Office. In May, the judge took the rare step of referring Waymo's case against Uber to the office to investigate possible trade secret theft.

Although the judge didn't take a position on whether a probe should be launched, the move raised the threat of federal criminal action against Uber at a time when it was already facing scrutiny over another internal program called “Greyball,” that reportedly helped the company skirt law enforcement in certain cities.

The letter from the U.S. attorney was under seal at the time of Tuesday's hearing, but testimony made it apparent that the federal prosecutors carrying out the investigation had pointed the judge to a letter Jacobs sent to Uber's associate general counsel, Angela Padilla, around late May. A partly redacted version of the letter handed over to Waymo's legal team, which is led by Charles Verhoeven of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, alleged Uber's so-called market analytics department was dedicated to “stealing trade secrets, code base and competitive intelligence from competitors.”

“The evidence brought to light over the weekend by the U.S. Attorney's Office and revealed, in part, today in court is significant and troubling,” said a Waymo spokesperson in a statement Tuesday afternoon. “The continuance we were granted gives us the opportunity to fully investigate this new, highly relevant information.”

At the evidentiary hearing, Jacobs testified that during his time at the company Uber employees used Wickr, which encrypts messages and deletes them shortly after they're sent. He said Uber also bought non-company laptops for employees from outside vendors and used MiFi spots rather than company Wi-Fi, possibly to keep information off of Uber's server.

Uber's lawyers have repeatedly argued during the course of the case that none of the 14,000 files that former Waymo star engineer Anthony Levandowski allegedly took when he left to form his own autonomous car company ended up on Uber servers after it purchased the startup and brought Levandowski aboard. Levandowski has so far invoked the Fifth Amendment in refusing to answer questions about the files Waymo says were taken. Uber fired Levandowski in May after Alsup urged the company to force him to testify and he refused.

According to portions of the letter that Jacobs read in court Tuesday morning, he was aware that Uber's market analytics department stole trade secrets from Waymo. Jacobs, however, denied this in his testimony. He claimed that he read the 37-page letter to Padilla, which was written by his lawyer, in only 20 minutes. He said he missed and did not approve of that particular statement. Jacobs also pointed to this lack of reading time when he disagreed with a point later in the letter, in which his lawyer wrote that Uber used ex-CIA operatives to ensure company secrecy in meetings, citing a presentation given by current Uber employee Ed Russo as a reason for this suspicion.

“We have a case where the witness varies from his lawyer's letter in significant ways,” Alsup said. “It's conceivable that he's been bought off by Uber.”

Jacobs denied being paid off by Uber, but did say that the ride-sharing company covered all of his expenses related to Tuesday's courtroom appearance. He also testified that he is set to receive more than $4 million as part of a deal reached with the company upon his departure in April, which included a non-disparagement agreement. Uber and Jacobs said nothing in the deal prevents him from being honest on the stand. He testified that he believes he was fired for not following Uber's culture of privacy and secrecy.

Current Uber employee Russo testified after Jacobs. Russo gave a presentation in May 2016 on the importance of privacy and protecting company secrets, during which he used then-CEO Travis Kalanick and former Waymo employee Levandowski as examples. He said he highlighted the extreme steps Kalanick and Levandowski took to in order to keep details of Uber's acquisition of Levandowski's startup private as a way to demonstrate the importance of security, not to imply that trade secrets had been stolen as part of the transaction. Russo told the court that he'd deleted the presentation, thinking it wasn't important and wouldn't be needed again.

Still, Alsup asked that Russo's presentation be submitted to the court along with other items that haven't been handed over, including Jacobs' resignation email, all documents related to ephemeral messages and a list of those who used them, and a list of employees using non-Uber laptops.

Google and Waymo will also have to disclose whether or not they've used anything similar to Wickr in the past.

Alsup told Uber's legal team that even setting up such a communication system is “as suspicious as can be.”

Alsup said Jacobs' letter to Padilla should be made public in full by 5 p.m. Tuesday. Visibly frustrated, he told Uber's lawyers he can't trust what they say because they've “lied so many times.”

“Your client is in a bad way now, because you've made me upset,” he said.

Yet the judge did give Uber a small win at the end of the hearing, refusing Waymo's request to close the court to the public while discussing deals and personal employee details such as compensation.

“I'm going to apply the Waymo standard that you've applied to Uber,” Alsup told Waymo's legal team. “Right now the deals will be made public. [There is] tons of stuff your lawyer has handed out to the press so they can write it up and make fun of Uber.”

However, information on Waymo's recent deal with Uber-rival Lyft Inc. will remain undisclosed and the court will not be open to the public during discussions of trade secrets and Waymo's future launch plans.

Jury selection in the case was scheduled to begin Wednesday morning, but the judge said the trial would be pushed back further. Uber in-house lawyer Padilla is set to testify Wednesday at another 8 a.m. hearing.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Nothing Is Good for the Consumer Right Now': Experts Weigh Benefits, Drawbacks of Updated Real Estate Commission Policies

Federal Judge Denies Build-A-Bear Workshop's Motion to Dismiss 'Squishmallow' Copyright Infringement Suit

Trending Stories

- 1Who Are the Judges Assigned to Challenges to Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order?

- 2Litigators of the Week: A Directed Verdict Win for Cisco in a West Texas Patent Case

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Womble Bond Becomes First Firm in UK to Roll Out AI Tool Firmwide

- 5Will a Market Dominated by Small- to Mid-Cap Deals Give Rise to a Dark Horse US Firm in China?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250