On Appeals: The Appellate Tiger's Tail

Irena Hauser applied to the County of Ventura for a permit allowing her to keep five tigers in her residential backyard near Malibu. After all, what could possibly go wrong? What went wrong in the Court of Appeal was that she was stalked by the presumptions favoring respondents on appeal, formidable beasts in the best of circumstances.

March 07, 2018 at 03:52 PM

6 minute read

Irena Hauser applied to the County of Ventura for a permit allowing her to keep five tigers in her residential backyard near Malibu. After all, what could possibly go wrong? What went wrong in the Court of Appeal was that she was stalked by the presumptions favoring respondents on appeal, formidable beasts in the best of circumstances.

The Court of Appeal began its decision in Hauser v. Ventura County Board of Supervisors by quoting William Blake:

Tyger! Tyger! Burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry!

This might have been meant ironically. On appeal, the most fearsome prospect for appellant is often the daunting asymmetry of the applicable rules.

Ms. Hauser's neighbors are apparently not cat lovers, as they opposed her application with a petition bearing about 11,000 signatures. The county planning commission and Board of Supervisors shot down the application. They found that Ms. Hauser had not proved two key elements: that the project was compatible with the area's planned uses, and that the project was not detrimental to the public interest, health, safety or welfare.

Undaunted, Ms. Hauser challenged the Board's decision by petitioning for a writ of administrative mandate pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure §1094.5. Administrative mandate is the mechanism for appealing an administrative decision in California, with the superior court sitting in effect as an appellate court. In the relatively small class of cases involving the applicant's “fundamental vested rights” (e.g., keeping a professional license, receiving government benefits), the superior court reviews findings of fact by reweighing the evidence under the independent judgment test.

Keeping tigers in one's backyard does not appear to be a fundamental vested right, and so the trial court did not apply the independent judgment test. In all other cases, “abuse of discretion is established if the court determines that the findings are not supported by substantial evidence in the light of the whole record,” under Code of Civil Procedure §1094.5(c). This is the familiar substantial evidence test that California appellate courts routinely apply in reviewing factual findings. Using this test, the superior court denied Ms. Hauser's writ petition.

The next destination in Ms. Hauser's legal safari was the Court of Appeal. Regardless of the standard of review applied in the trial court, an appellate court reviewing an administrative mandate decision addresses findings of fact under the substantial evidence test. This is the trap in which Ms. Hauser quickly found herself ensnared. For the respondent, the substantial evidence rule is a potent weapon, but for an appellant it is toothless.

Pouncing on the administrative mandate statute's “in light of the whole record” language, Ms. Hauser argued that the trial court erred in applying the substantial evidence test because it had failed to consider all the evidence in the record, including particularly the evidence that supported her petition. This evidence included the fact that she and her sister had attended an eight-day class on animal husbandry, safety and training; that some family member would always be present on the property with the tigers; that her own safety record had no blemishes; and that an escaped captive-born tiger allegedly poses almost no risk to the public.

The Court of Appeal observed that Ms. Hauser “misapprehends the substantial evidence rule,” a common refrain in appellate decisions reviewing factual determinations. The court therefore found it necessary to tame her enthusiasm for the rule. It explained that the trial court was indeed required to scout the entire record, but because she had not prevailed before the Board of Supervisors, it was required to track down and bring back only evidence in favor of the Board's decision. “[W]e look only to the evidence supporting the prevailing party … . We discard evidence unfavorable to the prevailing party as not having sufficient verity to be accepted by the trier of fact.”

Her argument was thus effectively caged by the substantial evidence test. The Court of Appeal had no trouble bagging enough substantial evidence to support the permit denial. The record showed that there were numerous homes close to Ms. Hauser's; that she had allowed tigers to roam free in her Hollywood backyard; that the eight-day animal husbandry course she touted imposed no written exam, no reading and, apparently, no risk of failing; and that captive tigers kept by other owners had escaped, and had mauled and even killed nearby humans.

Ms. Hauser fared no better with an argument of a different stripe—that she did not receive a fair hearing because some board members had met with opponents of her permit, and their attorney, before the meeting at which it denied her permit application. Here the Court of Appeal could again have invoked the substantial evidence rule but instead took aim with the presumptions of administrative litigation, which also tilt sharply against anyone appealing an agency decision. Specifically, unless a decision-maker has a financial interest in the outcome of the hearing, he or she is presumed to be impartial, and a contrary showing requires “clear evidence”—which Ms. Hauser had not presented. The most she could show was that some board members had met with opponents (and proponents) of the application, and that such contacts were discouraged by the board's policy manual. But the only action the manual required in the event of such contacts was disclosure at the board meeting, which the members had made. There was thus no evidence that her permit had been denied other than on the merits.

If there is a moral to this fable, it is that one should think twice before venturing into the appellate jungle without sufficient ammunition. Unfavorable findings are feral creatures that cannot be felled on appeal with opposing evidence, no matter how persuasive. And presumptions of regularity are the game wardens of administrative appeals, strictly limiting the circumstances in which a decision can be brought down.

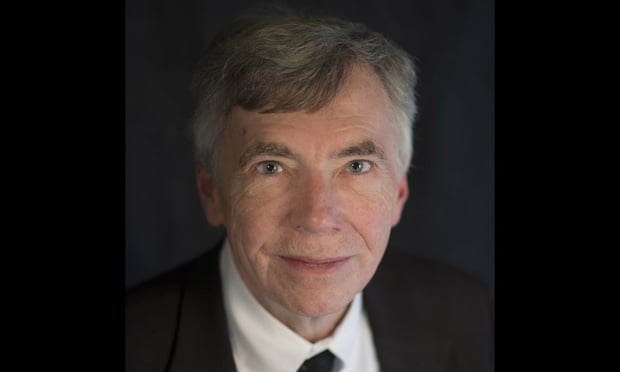

On Appeals is a monthly column by the attorneys of the California Appellate Law Group LLP, the largest appellate specialty boutique in Northern California. Charles Kagay is of counsel with the firm. He has decades of experience handling appeals that involve complex or novel legal questions and is certified by the State Bar as a California appellate specialist. Find out more about Charles and the California Appellate Law Group LLP at www.calapplaw.com.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

A Time for Action: Attorneys Must Answer MLK's Call to Defend Bar Associations and Stand for DEI Initiatives in 2025

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250