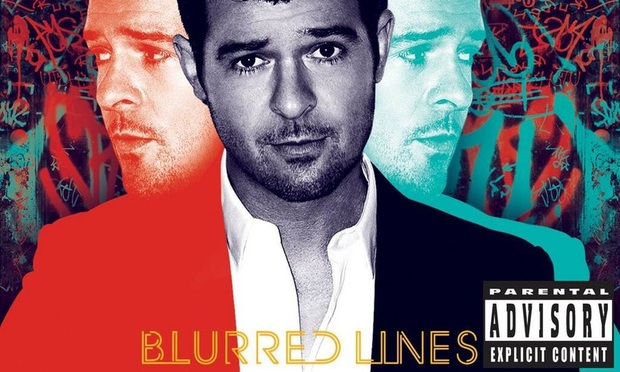

Ninth Circuit Upholds $5M 'Blurred Lines' Verdict Against Thicke, Pharrell

In dissent, Judge Jacqueline Nguyen warned the decision amounts to copyrighting a musical style and will permit "entire genres of music to be held hostage to infringement suits."

March 21, 2018 at 01:33 PM

4 minute read

The Ninth Circuit has upheld a $5 million jury award for copyright infringement against Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke.

A 2-1 majority led by Judge Milan Smith deferred to a jury's finding that Williams and Thicke copied Marvin Gaye's “Got to Give It Up” when they recorded “Blurred Lines.” The court also freed Clifford Harris, also known as T.I., of liability.

Dissenting Judge Jacqueline Nguyen accused her colleagues of being overly deferential to the jury in the case, saying the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit's decision will permit “entire genres of music to be held hostage to infringement suits.”

Williams v. Gaye is a win for Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer's Lisa Blatt and King & Ballow's Richard Busch, who argued on behalf of Gaye's heirs, who hold the copyright in “Got to Give It Up.”

Beyond the individual result, the case adds momentum to the idea among Ninth Circuit judges that jurors ought to be able to hear performances of allegedly infringed music performed by the author, rather than stripped down versions of the sheet music, even in cases governed by the 1909 Copyright Act. Blatt had told the Ninth Circuit it was like trying the case blindfolded and handcuffed.

That same issue was debated last week by a different Ninth Circuit panel reviewing a copyright claim over the Led Zeppelin song “Stairway to Heaven.”

Smith on Wednesday deemed the issue “unsettled” and said he believed that U.S. District Judge John Kronstadt of Los Angeles was the first to impose such a limit in the Williams case. He further suggested that Ninth Circuit precedent is not so restrictive.

“Blurred Lines” became an international sensation in 2013. Thicke, Williams and Harris are credited as co-authors. In an interview with GQ magazine, Thicke recalled telling Williams that “Got to Give It Up” was one of his favorite songs of all time, and that “we should make something like that, something with that groove.” The two started playing and “we literally wrote the song in about a half hour and recorded it.” Harris separately wrote a rap verse that was added to the song months later.

After the interviews were published, Gaye's heirs sued for infringement. The jury awarded about $7.3 million, which Kronstadt reduced to just over $5 million, plus a 50 percent royalty on future sales.

Smith emphasized in Wednesday's opinion that the Ninth Circuit had to review the jury's verdict deferentially, especially because neither party moved for judgment as a matter of law before the case was submitted.

He observed that expert witnesses testified to similarities between the songs' signature phrases, hooks, bass melodies, word painting and parlance. “Thus, we cannot say that there was an absolute absence of evidence supporting the jury's verdict,” Smith concluded. Judge Mary Murguia concurred.

Smith did reverse Kronstadt's post-trial ruling that Harris should be held liable along with Williams and Thicke.

Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan represented Williams, Thicke and their music publisher. Sidley Austin partner Mark Haddad represented Harris' music publishers.

Nguyen argued in dissent that the case never should have gone to a jury. Instead, Kronstadt should have granted summary judgment. “The majority allows the Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style,” Nguyen wrote.

The testimony from the Gaye heirs' experts was “the equivalent of finding substantial similarity between two pointillist paintings because both have a few flecks of similarly colored paint,” she wrote. The actual melody, harmony and rhythm of the songs are not objectively similar as a matter of law, she argued.

Nguyen repeatedly accused the majority of refusing to grapple with the musical elements of the song, many of which she said are shared by everyday compositions such as the “Happy Birthday” song.

Smith replied that the Supreme Court has forbidden appellate courts, except in rare circumstances, from reaching back to summary judgment decisions after cases go to trial. “The dissent improperly tries, after a full jury trial has concluded, to act as judge, jury and executioner,” Smith wrote, “but there is no there there, and the attempt fails.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Pistachio Giant Wonderful Files Trademark Suit Against Canadian Maker of Wonderspread

4 minute read

Hogan Lovells, Jenner & Block Challenge Trump EOs Impacting Gender-Affirming Care

3 minute read

Gen AI Legal Contract Startup Ivo Announces $16 Million Series A Funding Round

PayPal Faces New Round of Claims; This Time Alleging Its 'Honey' Browser Extension Cheated Consumers

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250