Divided State Supreme Court Upholds DNA Swabs for Felony Arrests

"We cannot ignore the safeguards built into the DNA Act," the majority ruling said.

April 02, 2018 at 06:22 PM

5 minute read

California Supreme Court Associate Justice Leondra Kruger. Credit: Jason Doiy/ Recorder

California Supreme Court Associate Justice Leondra Kruger. Credit: Jason Doiy/ Recorder California can continue collecting DNA samples from suspects arrested on, but not necessarily convicted of, felony charges, a divided state Supreme Court held Monday.

Writing for a 4-3 majority, Associate Justice Leondra Kruger said provisions of the voter-approved DNA Act of 2004 pass muster with state and federal law. The majority said it was mindful of defendant Mark Buza's privacy concerns, particularly given the broad privacy rights included in the state constitution, when he refused to allow deputies to swab his cheek after a 2009 arrest.

“But in so analyzing the arrestee's choice, we cannot ignore the safeguards built into the DNA Act: the limited nature of the information stored in databases on an arrestee … the legal protections against possible misuse of the profile or the sample (including felony sanctions for knowing improper use or dissemination); and the availability of procedures for removing the profile from the database and destroying the sample,” Kruger wrote.

“We have no record before us to show that these legal protections would have been violated or proved unworkable had defendant chosen to comply with the requirement to provide a DNA sample on booking,” Kruger added.

Kruger was joined in the majority by Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye and Associate Justices Ming Chin and Carol Corrigan.

Jayann Sepich, founder of the nonprofit DNA Saves, which filed an amicus brief in support of the state and prosecutors, said the court's ruling left her “jubilant.” Sepich said: “People who say this is an invasion of privacy don't know how the system works.” The database, she noted, includes identity protections and a limited number of DNA markers. DNA Saves was represented by Norton Rose Fulbright.

The decision is a blow for privacy and civil liberties advocates as well as public defenders who argued that collecting DNA samples from arrestees amounts to an illegal, warrantless search and seizure.

“I think the court took great pains to say the ruling was narrow and limited to those in Mr. Buza's position,” said Jennifer Lynch, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which filed a friend-of-the-court brief in the case.

“The court—and the justices in dissent point this out—almost abdicated its duty in trying to come up with this narrow opinion,” Lynch said.

While Buza's case was pending in the California courts, the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 rejected a defendant's Fourth Amendment challenge to Maryland law requiring DNA swabbing of those arrested for serious crimes.

That decision, the California Supreme Court wrote Monday, “significantly altered the terms of the debate.” California and Maryland laws on DNA samples, as well as the facts in the two cases, may be different, the court noted Monday, but not enough to find that Buza's Fourth Amendment rights were violated.

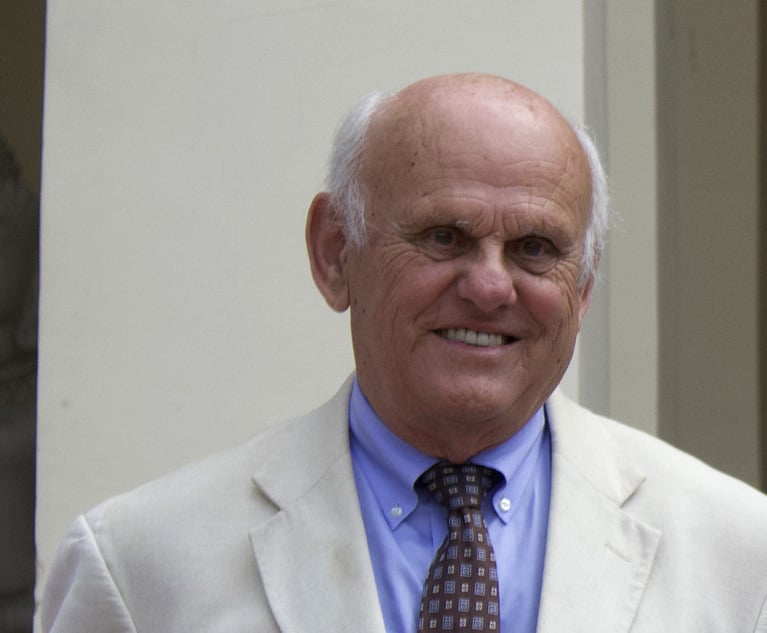

Justice Goodwin Liu. Credit: by Jason Doiy

Justice Goodwin Liu. Credit: by Jason DoiyWriting in dissent, Associate Justice Goodwin Liu called California's process for expunging DNA records burdensome and said that the state's retention of samples of those who are never prosecuted or are cleared of charges disproportionately hurts people of color.

“I have no doubt that law enforcement is aided by the collection and retention of massive numbers of DNA profiles,” Liu wrote. “But if those interests are enough to justify the collection and retention of DNA from persons who are arrested but not convicted, not charged, or not even found to be lawfully detained so long as they do not seek expungement, then it is not that far a step for the state to collect and retain DNA from law-abiding people in general.”

Liu was joined in dissent by Associate Justice Mariano-Florentino Cuellar and Justice Dennis Perluss of the Second District Court of Appeal, who was sitting by assignment. Cuellar issued a separate dissent.

Buza was arrested on Jan. 21, 2009, after a San Francisco police officer found him running away from a police car with burning tires. He was found with matches, an oil container and road flares, according a recounting of events by the court. After his arrest, but before a judge found probable cause for his detention, Buza refused to provide a DNA swab. In addition to arson, he was charged with a misdemeanor for his test refusal. The First District Court of Appeal reversed his misdemeanor conviction in 2014.

Fearing the DNA Act could be declared unconstitutional by a court, the California Legislature in 2015 approved changes—with a caveat—that would only allow a felony arrestee's DNA sample to be sent to the state database if a judge found probable cause. The legislation also set up an automatic expungement process. Those changes would only take affect, lawmakers said, if the state Supreme Court struck down the DNA Act. Because the state did not do that Monday, the legislation is now moot.

The Legislature should take another look at adopting those provisions, EFF's Lynch said.

The California Supreme Court ruling in People v. Buza is posted below:

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Judge Accuses Trump of Constitutional End Run, Blocks Citizenship Order

3 minute read

Hogan Lovells, Jenner & Block Challenge Trump EOs Impacting Gender-Affirming Care

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'A Waste of Your Time': Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

- 2Judge Extends Tom Girardi's Time in Prison Medical Facility to Feb. 20

- 3Supreme Court Denies Trump's Request to Pause Pending Environmental Cases

- 4‘Blitzkrieg of Lawlessness’: Environmental Lawyers Decry EPA Spending Freeze

- 5Litera Acquires Workflow Management Provider Peppermint Technology

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250