The Blurred Lines of Copyright Law Are Limiting Musical Creativity

The tactics of “legacy” interests—parties who own copyright interests in already-created songs but who won't be making any new music—are limiting the creative space for today's pop musicians

May 14, 2018 at 10:00 AM

5 minute read

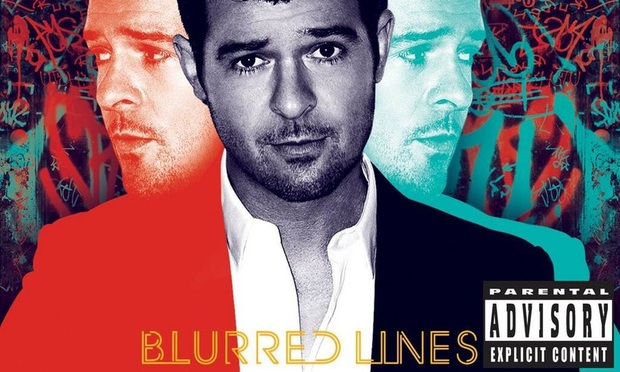

Sometimes it seems as if today's musicians spend as much time defending themselves against copyright infringement lawsuits as they do writing new music. Reading about suits against Ed Sheeran, Nicki Minaj, Pharrell Williams, Robin Thicke, and a host of others, one might be tempted to think that contemporary pop artists are just uncreative copycats.

The real issue, however, is that pop musicians simply may be running out of creative space. And this problem is being exacerbated by the behaviors of what we might call “legacy” interests—parties who own copyright interests in already-created songs but who won't be making any new music.

I have argued, with my colleagues Stefan Bechold and Christopher Sprigman, that any field of creative production has a certain “innovation space.” This space represents the world of possible solutions to a given creative problem. At the beginning of a field, whether sonata form or smartphone design, the innovation space is wide open. Anyone is free to do almost anything. Over time, however, portions of the innovation space get filled by intellectual property rights. The earliest creators fill up the innovation space with their copyrights and patents, limiting the options for newcomers. Newer creators are faced with a dilemma in which they must either find a portion of the innovation space that hasn't been claimed or pay a license fee to one of their predecessors.

The available innovation space for popular music has changed substantially over the last 75 years. Some innovations, most importantly rock and roll and rap, have dramatically expanded the areas of available musical creativity. Certain kinds of music that would have been unthinkable a generation or two earlier now fall squarely within the mainstream.

But there are reasons to be concerned. The scope of musical creativity likely isn't infinite. New research applying social science methods to aesthetics suggests that people's musical preferences are more limited than was previously believed. So while it's possible that we're on the cusp of another major evolution in musical taste, it's also possible that we're getting close to exhausting the varieties of music that people find appealing.

Moreover, whatever is happening at the boundaries of musical innovation, the innovation space at the core of popular music is becoming as crowded as a Tokyo subway car. Finding a pleasing melody that hasn't already been used by another artist is likely to get harder and harder. While innovations will create demand for new kinds of music, there will always be a sizable share of consumers who want new music that lies close to the center of traditional pop. Discovering ways to satisfy that demand is becoming increasingly difficult.

Unfortunately, the behaviors of some copyright owners are making this problem worse. The available innovation space depends on the scope or breadth of the rights granted to copyright owners. Copyright law doesn't just prevent exact duplication of a work; it also prevents “substantially similar” copies of work. Lately, the scope of musical copyrights seems to be expanding.

Active creators will typically have conflicting interests. They want copyright laws that are broad enough to give them strong rights against competitors but narrow enough to ensure there is always room in the innovation space for their next song. One day, they are potential plaintiffs with grievances against copyists, but the next day they could be potential defendants on the hook for millions of dollars.

But legacy interests—those parties who are no longer making music or who have inherited rights from previously active musicians—do not face these competing concerns. Since they're not creating any new music, they don't run the risk of being hauled into court. The statute of limitations will have run out long ago for any copyrights they or their parents may have infringed.

It's not surprising, then, that many of the recent lawsuits have been brought by legacy interests. Plaintiffs like Marvin Gaye's estate or older bands like The Hollies and Spirit will always prefer broader copyright protection, because they never have to worry about being defendants. They can push for copyright law to protect more than just a song's melody, but also its rhythm, feeling, or groove.

Many legacy interests from the 1960s and 1970s are the beneficiaries of being at the right place at the right time. Thirty years earlier, many of their contributions would have failed to gain recognition or copyright protection, as the stories of the many black progenitors of rock and roll indicate. Yet 30 years later, these artists would have faced a much more crowded innovation space and much greater risk of copyright infringement.

It's possible that overcrowding at the core of musical creativity will encourage artists to push the musical boundaries even further. But it's also possible that expanding music copyrights will simply make it harder (and more expensive) for newer artists to produce the kinds of music we want to listen to. Then, all we're likely to see is a massive wealth transfer from future consumers and artists to the heirs of those who lived and worked at just the right time. If older creators and their descendants are unwilling to stop the barrage of lawsuits, Congress and the courts should step in and determine the appropriate scope of copyright law. Leaving to a jury the open-ended question of whether two songs are “substantially similar” could end up hindering musical creativity.

Christopher J. Buccafusco is the director of the Intellectual Property & Information Law Program at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Rise of Female Breadwinners: Challenging Traditional Divorce Dynamics

4 minute read

An Overview of Proposed Changes to the Federal Rules of Procedure Relating to the Expansion of Remote Trial Testimony

15 minute read

Assessing the Second Trump Presidency’s Impact on College Sports

Cybersecurity Breaches, Cyberbullying, and Ways to Help Protect Clients From Both

7 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250