Everyone Wants a Piece of Fenwick & West

Silicon Valley's tech companies helped establish Fenwick as a force. Now outside law firms have eyes on the region, the work and Fenwick's lawyers.

January 31, 2019 at 05:30 AM

11 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The American Lawyer

Richard Dickson, chair of Fenwick & West. Photo: Jason Doiy/ALM

Richard Dickson, chair of Fenwick & West. Photo: Jason Doiy/ALM

Fenwick & West and Silicon Valley grew up together.

The firm was founded in 1972 by a handful of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton associates who fled the busyness of New York for a fresh start in Northern California. Since its inception, Fenwick has focused on representing the technology industry as it's grown from a fledgling enterprise into a dominant force in the American economy.

Over the years, that focus has helped Fenwick build relationships with some of the biggest names in tech, including Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Uber, Airbnb, Dropbox and Cisco.

While peer firms such as Cooley and Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati have expanded nationally and internationally, Fenwick has decided to hunker down in the tech corridors, with just five offices, in Mountain View and San Francisco, California; Seattle; New York; and Shanghai.

“We focus on a long-term sustainable approach,” Fenwick chair Richard Dickson says. “It's an approach that not every law firm makes or is in the position to make.”

In the course of its 47 years, Fenwick has grown to 335 lawyers. In that time, its clients have evolved from startups into multibillion-dollar companies that are reshaping the world's economy. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak's Apple Computer Inc., which the firm incorporated in 1977, now has a market valuation of about $700 billion. Another of the firm's longtime clients, Facebook, which was brought to the market by Fenwick's deal team in 2012, has more than 2 billion active monthly users worldwide and a valuation north of $400 billion.

Credit: Val Bochkov

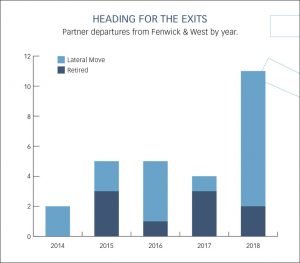

Credit: Val BochkovMuch of Fenwick's core strategy remains the same as it has from the start, Dickson says, even as its clients and the region have undergone rapid growth that has flooded the legal market with competition. As a firm that has historically placed a high value on collegiality and collaboration, partners have rarely left Fenwick in the past. But as the number of firms in the Bay Area increases—and as Fenwick's clients jostle for power on the world stage—Fenwick's laser-focused strategy is being put to the test. In 2018 alone, the firm watched 10 Bay Area partners walk out the door.

“Its success in generating a high concentration of clients from the tech industry has also made it a challenge to manage conflicts,” says one former Fenwick & West litigation partner who left several years ago. “I was running into a lot of conflicts that were part of the motivation for me to think about going elsewhere.”

According to data compiled by ALM Intelligence, from 2007 to 2017, 31 law firms opened new offices in the Bay Area. As they seek to establish a foothold in the region, many are targeting lawyers at Fenwick and elsewhere who grew up with the regional economy.

“It's a better way to grow my practice to go elsewhere,” says another former Fenwick & West partner who is now at a competing Am Law 100 firm. Leaving Fenwick offered the partner an opportunity: “being able to build something that is your own.”

Over a six-week stretch in August and September 2018, Fenwick lost five partners who averaged two decades with the firm. Facebook adviser R. Gregory Roussel went to Latham & Watkins; Jeffrey Vetter, the former co-chair of the firm's corporate finance and securities group, fled to rival Gunderson Dettmer Stough Villeneuve Franklin & Hachigian; IPO specialist William Hughes left for Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe; IP partner Darren Donnelly joined Polsinelli; and compensation and benefits partner Blake Martell jumped to Cooley.

Over a six-week stretch in August and September 2018, Fenwick lost five partners who averaged two decades with the firm. Facebook adviser R. Gregory Roussel went to Latham & Watkins; Jeffrey Vetter, the former co-chair of the firm's corporate finance and securities group, fled to rival Gunderson Dettmer Stough Villeneuve Franklin & Hachigian; IPO specialist William Hughes left for Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe; IP partner Darren Donnelly joined Polsinelli; and compensation and benefits partner Blake Martell jumped to Cooley.

According to data provided by Fenwick, the 10 Bay Area partners who headed for the exits in 2018 included two who are now retired, seven who went to competing firms, and litigation partner Virginia DeMarchi, who was selected for magistrate judgeship in San Jose, California. The group included a pair of private equity partners who left for Goodwin Procter in April, one of whom, Scott Joachim, was the founder and chair of the firm's private equity practice.

Meanwhile, Fenwick added nine laterals last year, all in New York.

Dickson admits there is always some impact felt by departures, but it hasn't been significant, he says, noting that Fenwick has retained the majority of its clients.

“We have invested far more in the laterals that we brought in than we got in terms of any benefits from the departing departures,” he says. Some, he adds, didn't have “meaningful practices.”

Legal recruiters who have observed Fenwick for years seem to have different opinions than Dickson.

“Some firms are more accustomed to partners coming in and going out. The departures generally hurt, but perhaps not as much for firms actively engaged in the Bay Area lateral partner market,” says one California-based recruiter who requested anonymity to discuss the firm. “But you don't see as much local partner attrition or acquisition happening in that firm. I wonder if it is more impactful because of that.”

Larry Watanabe, a California recruiter with Watanabe Nason & Schwartz, points out that among departing partners, “the vast majority joined firms more profitable than Fenwick.”

Fenwick shrugged off a sluggish 2016 to post record revenue of $374.9 million in 2017, and delivered $1.51 million in profits per equity partner. But other than Gunderson, which did not disclose its financial data, the lawyers leaving Fenwick all joined firms with higher revenues. Fenwick's profits are also below most of its competition.

The robust economy in the region has made firms “unusually aggressive” when recruiting for experienced corporate attorneys in San Francisco, Watanabe says. According to recruiters, firms that want to grow in the Bay Area have been offering compensation packages that include signing bonuses as high as $500,000 and million-dollar raises.

“The biggest challenge for Silicon Valley law firms is trying to establish or deepen their foothold and brand through the acquisition and retention of top partner talent,” says San Francisco-based recruiter Avis Caravello. “Because they are all trying to gain market share, for the right person, a key firm will pay whatever is necessary to get the deal done.”

Fenwick isn't the only indigenous firm feeling the pressure. Other San Francisco natives, including Wilson Sonsini, Cooley and Gunderson, have seen higher levels of departures in recent years.

Over the past two years, Wilson Sonsini has lost 17 partners in the Bay Area and 24 firmwide. Of the 17 Bay Area partners, 15 have joined rival firms, including five to Cooley, four to Latham & Watkins and two to Morrison & Foerster. The firm hired back a slew of its former lawyers last summer to give its practice in Silicon Valley a jolt.

Cooley says it lost 29 partners in the same time period, nine of whom were from the Bay Area, including four who left to join other Am Law 200 firms (Loeb & Loeb, Dorsey & Whitney, King & Spalding and Goodwin Procter).

Cooley, meanwhile, has added three partners to its Bay Area offices this year. In addition to its raid on Fenwick, the firm scooped up corporate partner David Segre from Wilson Sonsini, along with his former colleague T'Challa “T.J.” Graham for its technology transactions group.

Gunderson, which went over two years without losing a partner, recently watched three corporate partners decamp for Goodwin Procter, a Boston-based firm that is aggressively expanding in the Bay Area.

“Competition for sought-after lawyers is increasing all over the country. The competition is particularly acute in higher-rate markets, including the San Francisco Bay Area,” says Kent Zimmermann, an adviser at the Zeughauser Group. “There are many firms around the country that lack scale and have really high-quality lawyers in highly competitive markets. Many of those firms feel exposed to poaching by other firms with more scale that can pay their sought-after lawyers a lot more without breaking a sweat.”

According to ALM Intelligence's 2018 report “Barbarians at the Gate,” the United States' largest 250 law firms by attorney head count, known as the NLJ 250, have nearly doubled their geographic coverage since 2001, adding more than 1,000 offices within the U.S.

The San Francisco market has seen 47 market entries by NLJ 250 firms since 2001, ranking No. 1 among the metropolitan areas surveyed in the report. (Houston, Los Angeles and Chicago all boast more than 40 market entries.)

The report also shows that local firms in San Francisco have seen 13 percent more departures than additions since 2001. Latham & Watkins has increased its head count in San Francisco from 157 lawyers to 206 in that time. Meanwhile, at least three indigenous firms—Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison, Heller Ehrman and Thelen—have gone bankrupt.

“I advise firms that size relative to the markets on which they are focused—industries, practices and geographies—is typically important to occupy a defensible long-term position of pre-eminence,” Zimmermann says. “Size relative to market also allows the firm to become more resilient to poaching and also to build a larger profit pool with which to attract and retain top talent, build a deeper bench of sought-after lawyers, and distinguish the firm from competitors.”

Despite the partner departures, Dickson says 2018 was a record year for profits and revenue at Fenwick. Gross revenue rose by 15 percent from 2017 to $430 million, while profits per equity partner increased by 20 percent to $1.82 million. Fenwick's total head count increased from 321 in 2017 to 335, while its equity partnership dropped by one to 83.

“I think our partner compensation is competitive. I think the vast majority of our partners greatly like working together,” Dickson says. “They see the benefit of our very focused platform, they see their practices and their opportunities improve as a result of the uniqueness our platform.”

As one former Fenwick partner puts it, “I wouldn't have invested so much time at the firm if I didn't believe that a smaller player could fight above its weight.”

Dickson, who has been at Fenwick for over 25 years, was officially elected as the firm's chair in 2014. Former chair Gordon Davidson, an icon in Silicon Valley's deal scene, has returned to his full-time corporate practice.

“The leadership structure has generally remained the same,” Dickson says. He notes that growing the firm into a “larger and more complex organization” has included some additional management tasks.

The firm has no plans to dramatically increase its practice offerings, compensation structure or partnership size, Dickson says. However, it is considering expanding its footprint in the United States or abroad “when there is clearly a critical mass opportunity that enables us to be strong while maintaining our focus on technology and life science.”

Los Angeles and Boston could present opportunities for growth, Dickson says. Meanwhile, Fenwick will continue to grow its New York office.

“We will stick with our strategy of being extremely focused on technology and life science,” he says. “The easy way to grow in size would be to do other things, and we are not going to do that.”

Fenwick will continue to face competition from firms trying to grow in the Bay Area, but Dickson says it doesn't currently have any interest in a merger. Despite recent challenges, recruiters say Fenwick has an established brand that will help it weather the storm. And with 2019 expected to be a busy year for IPOs, it has plenty of work coming its way.

“Fenwick,” Watanabe says, “is not going anywhere.

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Cleary Nabs Public Company Advisory Practice Head From Orrick in San Francisco

The Rise of Female Breadwinners: Challenging Traditional Divorce Dynamics

4 minute read

An Overview of Proposed Changes to the Federal Rules of Procedure Relating to the Expansion of Remote Trial Testimony

15 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250