'Epic' Impact: How a Major SCOTUS Decision in Favor of Arbitration Is Shaping the Landscape for Workplace Lawsuits

“[Epic] changes the dynamics in a profound way,” said Gerald Maatman, a partner at Seyfarth Shaw in Chicago. “It's one of the most important decisions from the Supreme Court that impacts workplace issues.”

February 28, 2019 at 05:00 AM

10 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

Illustration by Taylor Callery

Illustration by Taylor Callery

The case before U.S. District Judge Gerald McHugh Jr. was not unlike others he'd seen before. A woman alleged sexual harassment in the workplace so severe she had been forced to quit her job. Her former employer, a global talent agency called MarketSource, was arguing that the whole dispute ought to be in front of an arbitrator—not in a public courtroom.

McHugh, sitting in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, left no doubt about his misgivings, writing “there is legitimate cause for concern when a parallel system of dispute resolution supplants the courts.” But in the face of a growing constellation of U.S. Supreme Court decisions favoring arbitration contracts, the judge concluded in a decision last November that he had little choice but to side with the company.

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court's split decision in Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, which further bolstered the Federal Arbitration Act, that outcome has been increasingly common for workers who try to take their employers to court. Claims of persistent sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace, fast-food workers shorted on pay and gig economy contractors fighting for employee status have all been routed to arbitration in decisions citing Epic. In less than a year, the ruling has proven to be a strong weapon for the pro-arbitration defense bar.

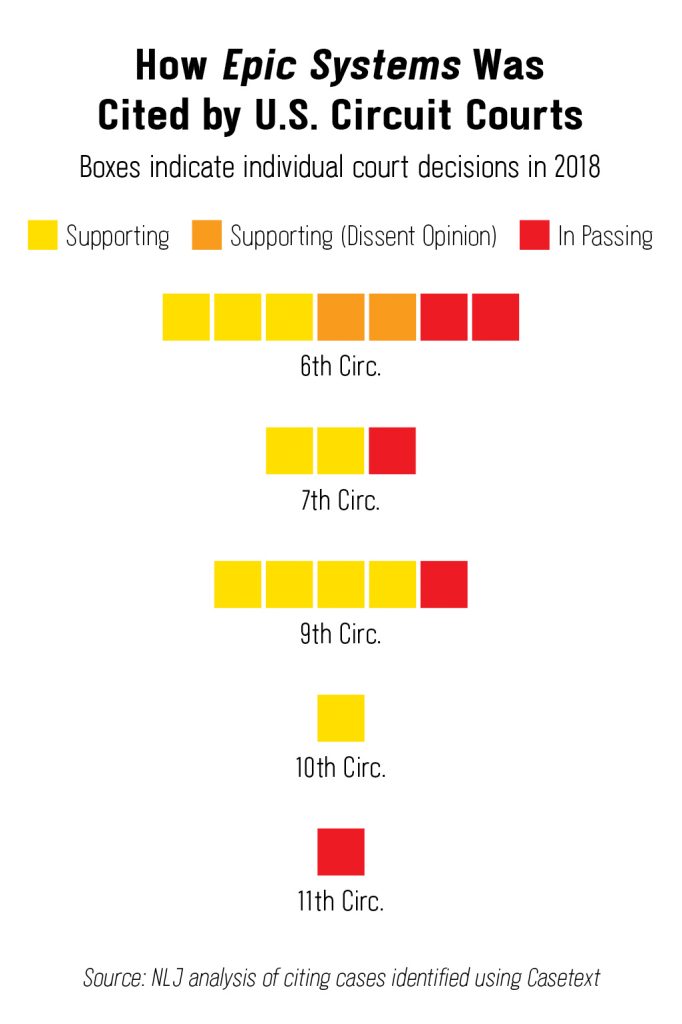

In collaboration with San Francisco-based legal research company Casetext, The Recorder affiliate The National Law Journal analyzed 92 decisions from U.S. courts of appeal and federal district courts that cited Epic in the seven months between when it was handed down last May and the end of 2018. Among those cases, 10 circuit court and 49 district court decisions centered on arbitration and dealt with workplace claims—and the majority either compelled arbitration or revived it as a live issue.

“[Epic] changes the dynamics in a profound way,” said Gerald Maatman, a partner at Seyfarth Shaw in Chicago. “It's one of the most important decisions from the Supreme Court that impacts workplace issues.”

Scale of the Impact

In Epic, which reviewed a trilogy of labor cases from the Fifth, Seventh and Ninth circuits, the Supreme Court majority concluded that, in the eyes of Congress, “arbitration had more to offer than courts recognized—not least the promise of quicker, more informal and often cheaper resolutions for everyone involved.”

The high court found the arbitration contracts at issue—which required employees to arbitrate individually rather than collectively—were to be enforced as written. Critically, the majority concluded that arbitration contracts that waive an employee's right to bring class or collective claims do not violate the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA).

That finding has rippled through dozens of worker lawsuits, many of which had used the NLRA argument to attempt to nullify agreements to arbitrate disputes. It has impacted headline-grabbing cases, such as a pair of now-unraveled class actions against ride-hail giant Uber, as well as many other suits that would be unlikely to garner much public attention.

The NLJ's analysis revealed the following statistics about cases citing Epic:

- About 63 percent of decisions citing Epic—across all case types—broke in favor of the defendant, although the fact patterns in many cases differed widely.

- The bulk of the cases were class actions. About 53 percent of the circuit court cases citing Epic, and roughly 71 percent of the district court cases, were class actions. Of class actions in both district and circuit courts, 53 percent were compelled to arbitration, and in another 6 percent arbitration was revived as a live issue after Epic.

- The most common case type centered on wage-and-hour claims, but there were a handful of sexual harassment and discrimination cases, too. Around 47 percent of circuit court cases, and just under 51 percent of the district court cases, were wage-and-hour cases. Other cases citing Epic involved securities claims, alleged credit reporting violations and immigration proceedings.

- In the district courts, most of the cases centering on arbitration that involved workplace claims—allegations of wage-and-hour violations, sexual harassment at work, workplace discrimination or worker misclassification—67 percent were compelled to arbitration. That accounted for 33 cases. In one additional case, arbitration was revived as a live issue. About 12 percent of decisions denied arbitration, and roughly 18 percent resulted in some other outcome.

A Battleground Shift

These findings reflect only a snapshot of the shifting dynamics in courts and companies around the country. State courts have begun taking cues from Epic as well, plaintiff attorneys are plotting their new moves, and employers are adjusting to a new normal while balancing social considerations with newfound legal security.

“Basically, the playing field has changed. The ruling gave new weapons to the defense bar and employers to combat class action litigation,” Seyfarth Shaw's Maatman said. “This impacts companies every day, practicing in the courtroom, but it also has an impact in a very practical way.”

Maatman, commenting on the NLJ's analysis of cases citing Epic, noted the data would not capture how many plaintiffs dropped claims or decided to avoid the process altogether.

“It changes the size of a case, the approach to the case, the ability in the class action to find other claimants,” said Maatman, who represents employers around the country. “What I'm seeing practically speaking is companies are seeing demand letters from lawyers seeking payment in wage-and-hour cases. Before Epic, I would see a class action.”

The pro-arbitration defense bar arguably already had the upper hand in the wake of earlier Supreme Court decisions in American Express v. Italian Colors Restaurant and AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion.

The pro-arbitration defense bar arguably already had the upper hand in the wake of earlier Supreme Court decisions in American Express v. Italian Colors Restaurant and AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion.

Kalpana Kotagal, a partner at Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll, said Epic raised concerns because it eliminated the open angles that could provide a clear channel for collective legal action. She said the new process will create inefficiency for both sides.

“At some point, defendants will tire of contending with many findings alleging the same things,” Kotagal said. “In the meantime, the folks representing employees will not go away. These issues are important. The claims are still there. Employees need to vindicate their rights. Creative lawyers will pursue create strategies. Will Epic make that harder? There's no question about that.”

In a few cases, plaintiff firms have sought to beat defense attorneys at the arbitration game by filing thousands of arbitration cases at once, and then demanding that the arbitration fees be paid by the companies up front. Firms representing Uber, ride-hail rival Lyft, and Chipotle face such an avalanche of arbitration proceedings.

David Horton, a law professor at University of California, Davis School of Law, co-wrote a study late last year that found plaintiffs have successfully used mandatory arbitration as a tool—calling mass arbitrations the “ghosts of class actions.”

“The Supreme Court has made it really hard for class actions to survive. Plaintiffs' attorneys are trying to find ways to deal with suing companies for widely dispersed claims,” Horton said. “They're engaged in guerrilla warfare.”

But the study, which Horton penned with fellow professor Andrea Chandrasekher, suggested this is likely not a lasting strategy for legal battles against corporate defendants.

A Push Forward or a Roll Back?

Other recent studies also suggest the scales have been tilted in favor of employers, and that arbitration can discourage employees from coming forward with claims. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission said in a statement in 1997, which has not been rescinded, that the private arbitral system is “structurally biased against applicants and employees.”

Meanwhile, more than half of employers in the country are subject to mandatory employment contracts, and a third of those include class action waivers, according to the Economic Policy Institute. This has risen from 2 percent in 1991 to 25 percent in the early 2000s, to 55 percent of workers today.

That survey also found that employees in low-wage workplaces, women and African-Americans are more likely to be subject to mandatory arbitration agreements. Nearly 65 percent of workplaces where the average wage is less than $13 an hour also require these agreements, the study found.

The number of companies who use these agreements could increase. After Epic, employers who were “sitting on the sidelines” are now looking to adopt this type of contract with workers, said Kathleen McKenna, a Proskauer Rose partner in New York who specializes in labor and employment.

Public sentiment about arbitration agreements has shifted since #MeToo changed the conversation around harassment and discrimination. State and local lawmakers have pushed bills that would restrict mandatory arbitration, and federal legislation has also been proposed to counteract Epic. These factors create a delicate balancing act for companies.

Large companies, including Microsoft Corp., Google Inc. and Facebook, recently announced changes to internal policies that either eliminate or make exceptions for harassment claims in the agreements. But few have fully abandoned arbitration and others have taken steps to further enforce these agreements and lash out against employees who tried to file lawsuits.

Yet some employment attorneys still predict the trend is likely to move toward more arbitration, not less. Employers turn to arbitration because it can be a more expedient and private process. Noting that arbitration initially gained traction with union and company meditation processes, historically, McKenna said companies continue to prefer it because it limits risk and prevents the possibility of a “runaway jury” award.

“Some folks reacted with internal pressures,” McKenna said of the moves by some companies to scale back the scope of their arbitration agreements, “but those who practice in the space worry that is the wrong message to send on a philosophical level.”

Andrew Melzer, partner and co-chair of Sanford Heisler Sharp's wage-and-hour practice, has predicted the practical impact of Epic may be limited if employers continue to roll back some of their mandatory arbitration agreements, including law firms.

“There has been a substantial public outcry against confidentiality agreements and arbitration clauses, particularly in the MeToo era,” he said. “In light of the backlash, some employers have been reluctant to impose such provisions on their employees.

He added, “The law in this area has become so skewed that we expect to see a continued backlash against arbitration—potentially leading to legislative action.”

You can view and download the full data set that we assembled in reporting this story, and take a look at how we conducted our analysis, over on GitHub. Our goal in presenting this to our audience is to “show our work” and promote greater transparency around a legal issue with wide public interest and significance.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms Look to Gen Z for AI Skills, as 'Data Becomes the Oil of Legal'

Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

5 minute read

'A Warning Shot to Board Rooms': DOJ Decision to Fight $14B Tech Merger May Be Bad Omen for Industry

Apple Files Appeal to DC Circuit Aiming to Intervene in Google Search Monopoly Case

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1There's a New Chief Judge in Town: Meet the Top Miami Jurist

- 2RIP DOJ FCPA Corporate Prosecutions

- 3Federal Trade Commission’s Updates to the Health Breach Notification Rule Now In Effect

- 4I’m A Lawyer, What Can I Sell?

- 5Internal GC Hires Rebounded in '24, but Companies Still Drawn to Outside Candidates

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250